Carole "Imani" Parker and Jobs for Youth Apprenticeship Program

For the month of June, poet, educator, and inspirational speaker Carole "Imani" Parker blogs about her work with the P&W–supported Jobs for Youth Apprenticeship Program (JFYAP) at Medgar Evers College, a job readiness program she once directed.

As former director of JFYAP, I write this entry with a sense of joy, sadness, and pride. When I first started working at JFYAP in 1995, it had been closed for two years. I am privileged to have been able to watch the program grow for more than fifteen years. Unfortunately, due to the current recession, the program, which was funded by the New State Department of Labor, lost its funding and was forced to close in December 2011. Because of its collaboration with the GED Plus-Division of the New York City Department of Education and Medgar Evers College, however, the remaining students in the program have been allowed to complete their education at the college.

JFYAP was established as an academic enrichment/career development program. The program was designed to provide services to “at risk” youth as well as young people who had either dropped out of traditional high schools or migrated to the United States from other countries. For more than seventeen years, JFYAP assisted hundreds of students to reach their academic and vocational goals.

Some students came with a myriad of issues, including gang involvement, illiteracy, and substance abuse. With a caring staff and creative P&W–supported writers, such as George Edward Tait, Abu Muhammad, and Radhiyah Ayobami, many of the students were able to transform their negative conditions and behavior through the art of creative writing.

Photo: Carole Imani Parker.

Support for Readings/Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, the A.K. Starr Charitable Trust, and Friends of Poets & Writers.

Most writers acknowledge the benefit of retreat. Getting away enabled me to turn off technology and turn any distractions into sustenance: cooking, watching the lake shift and move, or watching a deer watching me. In this way some retreats are a coming towards: towards nature, towards community, towards solitude, towards discipline. I am grateful to have benefited from different kinds of retreats where I have learned about the craft of poetry, the power of community, and the sacredness of solitude.

Most writers acknowledge the benefit of retreat. Getting away enabled me to turn off technology and turn any distractions into sustenance: cooking, watching the lake shift and move, or watching a deer watching me. In this way some retreats are a coming towards: towards nature, towards community, towards solitude, towards discipline. I am grateful to have benefited from different kinds of retreats where I have learned about the craft of poetry, the power of community, and the sacredness of solitude. he celebration began the evening of Friday, April 27, when more than eighty people gathered at the Hart Senior Center in downtown Sacramento for a pre-conference reception. Attendees sipped port wine and dunked fresh fruit into a multi-tiered chocolate fountain while mingling with conference faculty and fellow participants. Faculty greeted participants, signed books, and read their own work for the crowd.

he celebration began the evening of Friday, April 27, when more than eighty people gathered at the Hart Senior Center in downtown Sacramento for a pre-conference reception. Attendees sipped port wine and dunked fresh fruit into a multi-tiered chocolate fountain while mingling with conference faculty and fellow participants. Faculty greeted participants, signed books, and read their own work for the crowd. After a catered Italian lunch accompanied by an enticing slice of strawberry cheesecake, Ginny McReynolds, CRC Dean of Humanities and Social Science, gave a keynote talk about the importance of writing on a regular basis. Once the afternoon workshops concluded, participants returned to submit their evaluations for prizes donated by local restaurants, private individuals, and a local winery. As attendees departed, many reported that they had met new people and enjoyed the chance to network and eat great food. Many promised to return next year, as their life stories continue to unfold.

After a catered Italian lunch accompanied by an enticing slice of strawberry cheesecake, Ginny McReynolds, CRC Dean of Humanities and Social Science, gave a keynote talk about the importance of writing on a regular basis. Once the afternoon workshops concluded, participants returned to submit their evaluations for prizes donated by local restaurants, private individuals, and a local winery. As attendees departed, many reported that they had met new people and enjoyed the chance to network and eat great food. Many promised to return next year, as their life stories continue to unfold.  Nelson asked us to pay particular attention to the construction of the poetic line. Through a sequence of assignments we experienced how careful and intentional construction could lead to a meaningful, surprising, and exciting composition. Formal verse provides the writer with added parameters. Nelson’s poetry exhibits how such constraints used skillfully can produce poems that are wild, challenging, liberating, and free.

Nelson asked us to pay particular attention to the construction of the poetic line. Through a sequence of assignments we experienced how careful and intentional construction could lead to a meaningful, surprising, and exciting composition. Formal verse provides the writer with added parameters. Nelson’s poetry exhibits how such constraints used skillfully can produce poems that are wild, challenging, liberating, and free.  What are your reading dos?

What are your reading dos? The inspiration flows in both directions. Just as frequently as I find myself using my teaching practice to inform my artistic practice, I also bring strategies, poems, questions, and obsessions from my writing life back into the classroom. If I look back at periods when I have been teaching a particular group of students and then examine the poems that I wrote during that time I can often find traceable themes and continuities. For five weeks of teaching and five weeks of writing we seemed to return to these central questions: What do we invoke? What do we want? What do we dream?

The inspiration flows in both directions. Just as frequently as I find myself using my teaching practice to inform my artistic practice, I also bring strategies, poems, questions, and obsessions from my writing life back into the classroom. If I look back at periods when I have been teaching a particular group of students and then examine the poems that I wrote during that time I can often find traceable themes and continuities. For five weeks of teaching and five weeks of writing we seemed to return to these central questions: What do we invoke? What do we want? What do we dream? In these workshops, I am not only aware of what I receive from and give to writers, but also how the group itself develops its own identity and offers its own gifts. When we create a space that allows us to freely write about joy, pain, and longing and encourages others to listen to these often long-withheld emotions—amazing changes can happen. Regardless of differences in age and experience, we all write from a deep, secret place. And then we share, which helps us feel a growing sense of peace and helps to diminish loneliness.

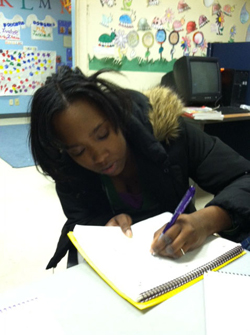

In these workshops, I am not only aware of what I receive from and give to writers, but also how the group itself develops its own identity and offers its own gifts. When we create a space that allows us to freely write about joy, pain, and longing and encourages others to listen to these often long-withheld emotions—amazing changes can happen. Regardless of differences in age and experience, we all write from a deep, secret place. And then we share, which helps us feel a growing sense of peace and helps to diminish loneliness. For five weeks in the fall of 2011, young women from G.E.M.S. showed up to write in community. We gathered around a table, asking unanswerable questions and drafting poems that were received with admiration, thoughtful critique, and applause. In my work as an educator, a student has never failed me. When it comes to poetry and writing, young people always have something to share—it is my job to provide a way for students to enter into a poem.

For five weeks in the fall of 2011, young women from G.E.M.S. showed up to write in community. We gathered around a table, asking unanswerable questions and drafting poems that were received with admiration, thoughtful critique, and applause. In my work as an educator, a student has never failed me. When it comes to poetry and writing, young people always have something to share—it is my job to provide a way for students to enter into a poem. As one of the festival co-organizers, I had the opportunity to invite a few authors to visit the festival, and I tried to present authors who seemed to support the mission of the festival: to celebrate small press literature.

As one of the festival co-organizers, I had the opportunity to invite a few authors to visit the festival, and I tried to present authors who seemed to support the mission of the festival: to celebrate small press literature.