Thomas Lux's Reading at the Marc Straus Gallery

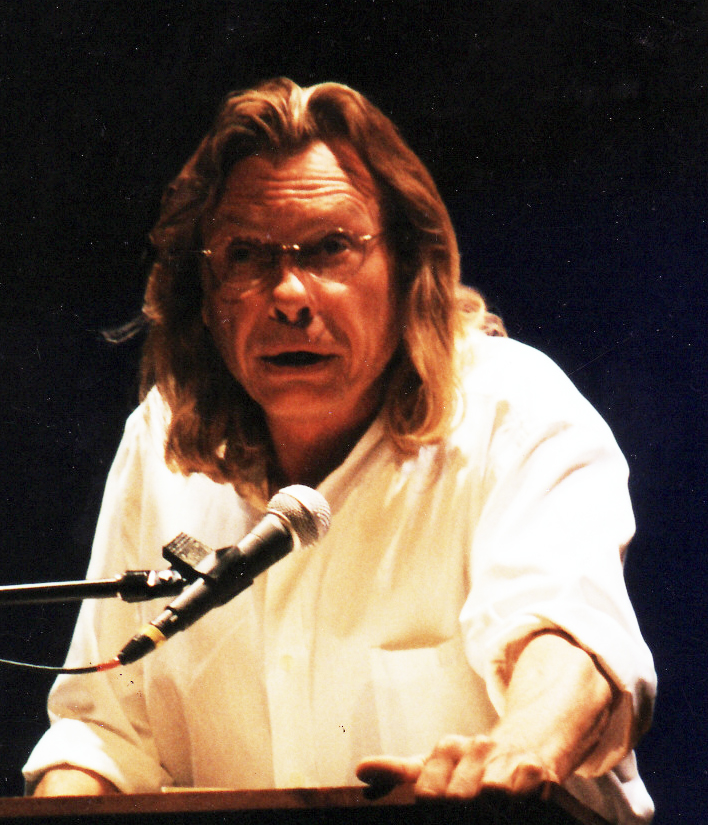

Thomas Lux blogs about his P&W-funded reading at Marc Straus, an art gallery in New York City. Lux is Bourne Professor of Poetry at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He has two new books out this fall—the poetry collection Child Made of Sand (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and his nonfiction debut From the Southland (Marick Press).

I’ve never written a blog before and I’ve only read a handful of them. I can use e-mail (an excellent invention), and the computer is a very a sophisticated typewriter. I remember when Poets & Writers Magazine started. I believe the early issues were stapled, short newsletters. Maybe mimeographed? Now it’s grown in range and depth and is an important read for most contemporary writers.

It was once possible to keep up with virtually all of contemporary poetry—the number of presses and literary magazines were finite, and limited to print. Books from big houses and books from independent presses (then called “small presses”) looked pretty ugly, frankly, compared to books today, because of our enormous improvements in printing technology. They're many more venues for poetry today. Poetry is showing up everywhere.

P&W recently put a few bucks in my pocket. In mid-September, I gave a reading in New York City with Marc Straus at the Marc Straus Gallery on Grand Street. I’ve known Marc for over twenty years since he took a class of mine at the 92nd Street Y. We became friends. Marc’s a medical oncologist and, with his wife, Livia, a major collector of contemporary art. Marc is also a poet. He’s published three books: One Word, Not God, and Symmetry. Many of his poems deal with his experience as an oncologist. He writes sometimes in the voice of the doctor and sometimes in the voice of a patient. Only a real poet and oncologist can write the poems he writes. He recently opened his own art gallery, directly across Grand Street from a drapery store his father owned and ran many decades ago, and where Marc worked as a child. Here’s one of his poems, "Scarlet Crown":

I met a man my age running a greenhouse.

He pointed to the pots with pride, saying

they contained a thousand separate cacti.

Not much interest in these when I started,

he said. He pointed to the barbed bristles

(glochids), the bearing cushions (areoles),

and the names of many of the 200 genera:

Brain, Button, Cow-tongue, Hot Dog, Lace,

Coral, and Silver ball. In my work,

I said, I’m burdened with such straight-

forward terms: lung cancer, lymphoma,

breast cancer, leukemia. I’d love

to switch to: Pond-lily, Star,

or Scarlet Crown. Really, he said,

pointing to other plants, named

Hatchet, Devil, Dagger, Hook, and

Snake—or perhaps a diagnosis of this:

Rat-tail, White-chin, Wooly-torch,

or Dancing Bones.

The show up at the time was by a painter, seventy-nine-year-old Charles Hinman, who’d only recently received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and who’d been painting in relative obscurity for decades in a rent controlled studio just a few blocks from the gallery. I like reading surrounded by art. (Note: the show was a big hit.) Afterwards, someone handed me a rather generous check from P&W. And ditto another check the next night at a Page Meets Stage reading at Poets House. I read with a spoken-word artist/poet named Jon Sands. (To be continued in the next blog post...)

Photo: Thomas Lux.

Support for Readings/Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, The Cowles Charitable Trust, the Abbey K. Starr Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

What are your reading dos?

What are your reading dos? What happens when we engage the spaces between poetry and science, between art and geography, between place and philosophy? What happens when all those categories get mixed up? I’d call the new arrangements that emerge a hybrid poetic geography, in which different fields of thought and knowledge collapse into each other.

What happens when we engage the spaces between poetry and science, between art and geography, between place and philosophy? What happens when all those categories get mixed up? I’d call the new arrangements that emerge a hybrid poetic geography, in which different fields of thought and knowledge collapse into each other. A poetry slam, we now know, has rules. Poems are orally presented, in front of a microphone. The poems must fit in a time slot of three minutes. Structure, rhyme, and meter are optional. Poets come to the front of the audience, one at a time, and deliver their work. Then the judges (there were five of us at the September slam) hold up cards ranging from one to ten, and fractions thereof. So, the poet might receive an 8.7 or a 9.3, a la Olympics. A time-/scorekeeper records the scores, discards the high and low, and averages the remainder.

A poetry slam, we now know, has rules. Poems are orally presented, in front of a microphone. The poems must fit in a time slot of three minutes. Structure, rhyme, and meter are optional. Poets come to the front of the audience, one at a time, and deliver their work. Then the judges (there were five of us at the September slam) hold up cards ranging from one to ten, and fractions thereof. So, the poet might receive an 8.7 or a 9.3, a la Olympics. A time-/scorekeeper records the scores, discards the high and low, and averages the remainder. On October 1, 2012, Inprint, Inc., and the Poetry Society of America in association with Nuestra Palabra presented a panel discussion, Red, White & Blue: Poets on Politics, featuring Sandra Cisneros and Tony Hoagland and moderated by the Poetry Society’s executive director Alice Quinn. The gathering, held at the University of Houston, drew a mix of students and community members and there was a rich conversation about the urgency of poets to speak in response to social issues. Both Cisneros and Hoagland read work by poets they admire, followed by a discussion about the importance of giving voice to community. Sandra closed with a poem by

On October 1, 2012, Inprint, Inc., and the Poetry Society of America in association with Nuestra Palabra presented a panel discussion, Red, White & Blue: Poets on Politics, featuring Sandra Cisneros and Tony Hoagland and moderated by the Poetry Society’s executive director Alice Quinn. The gathering, held at the University of Houston, drew a mix of students and community members and there was a rich conversation about the urgency of poets to speak in response to social issues. Both Cisneros and Hoagland read work by poets they admire, followed by a discussion about the importance of giving voice to community. Sandra closed with a poem by  What makes your workshops unique?

What makes your workshops unique? th teenagers, I wanted to work more with adults. So Shaista and I began planning a workshop that spoke to the rootless-ness we both felt, whether we were in Karachi, Houston, or somewhere else. Shaista and I dedicated much thought to our workshop title—just as VBB co-founders and I had spent time honing in on the right title for “our” organization three years earlier. We finally agreed on “Voices of the Displaced,” a title that rang true for us. It also attracted a pool of Houston-based writers who were born in other countries or elsewhere in the United States, who had come from communities of color, or identified themselves as GLBT/queer. Project Row Houses offered us a meeting space and co-sponsored the series. We sent out emails inviting people to join—VBB didn’t even have a website at that time. Our first group was intimate with only six participants, but over time, the group expanded. We always brought food and drinks and our gatherings offered formal writing but also a sense of community.

th teenagers, I wanted to work more with adults. So Shaista and I began planning a workshop that spoke to the rootless-ness we both felt, whether we were in Karachi, Houston, or somewhere else. Shaista and I dedicated much thought to our workshop title—just as VBB co-founders and I had spent time honing in on the right title for “our” organization three years earlier. We finally agreed on “Voices of the Displaced,” a title that rang true for us. It also attracted a pool of Houston-based writers who were born in other countries or elsewhere in the United States, who had come from communities of color, or identified themselves as GLBT/queer. Project Row Houses offered us a meeting space and co-sponsored the series. We sent out emails inviting people to join—VBB didn’t even have a website at that time. Our first group was intimate with only six participants, but over time, the group expanded. We always brought food and drinks and our gatherings offered formal writing but also a sense of community. In Sanskrit, “dakshina” means “offering.” Beyond performing both bharata natyam and modern dance, Dakshina/Daniel Phoenix Singh Dance Company offers the community events that celebrate important figures in South Asian history through other art forms.

In Sanskrit, “dakshina” means “offering.” Beyond performing both bharata natyam and modern dance, Dakshina/Daniel Phoenix Singh Dance Company offers the community events that celebrate important figures in South Asian history through other art forms. In Pakistan, September 21, 2012, was marked as a day of remembrance for Prophet Mohammad in response to a film that went viral and sparked violence in parts of North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Knowing that the time difference between Houston and Pakistan was ten hours, I began checking online Pakistani newspapers as soon as I awoke. By the end of twenty-four hours, more than twenty people had been killed and six cinema houses had been burned. Meanwhile, progressive and secular communities that formed Pakistan’s majority were posting comments asking why extremists weren’t using their energies to offer help to the southern part of the country, where floods once again disrupted lives.

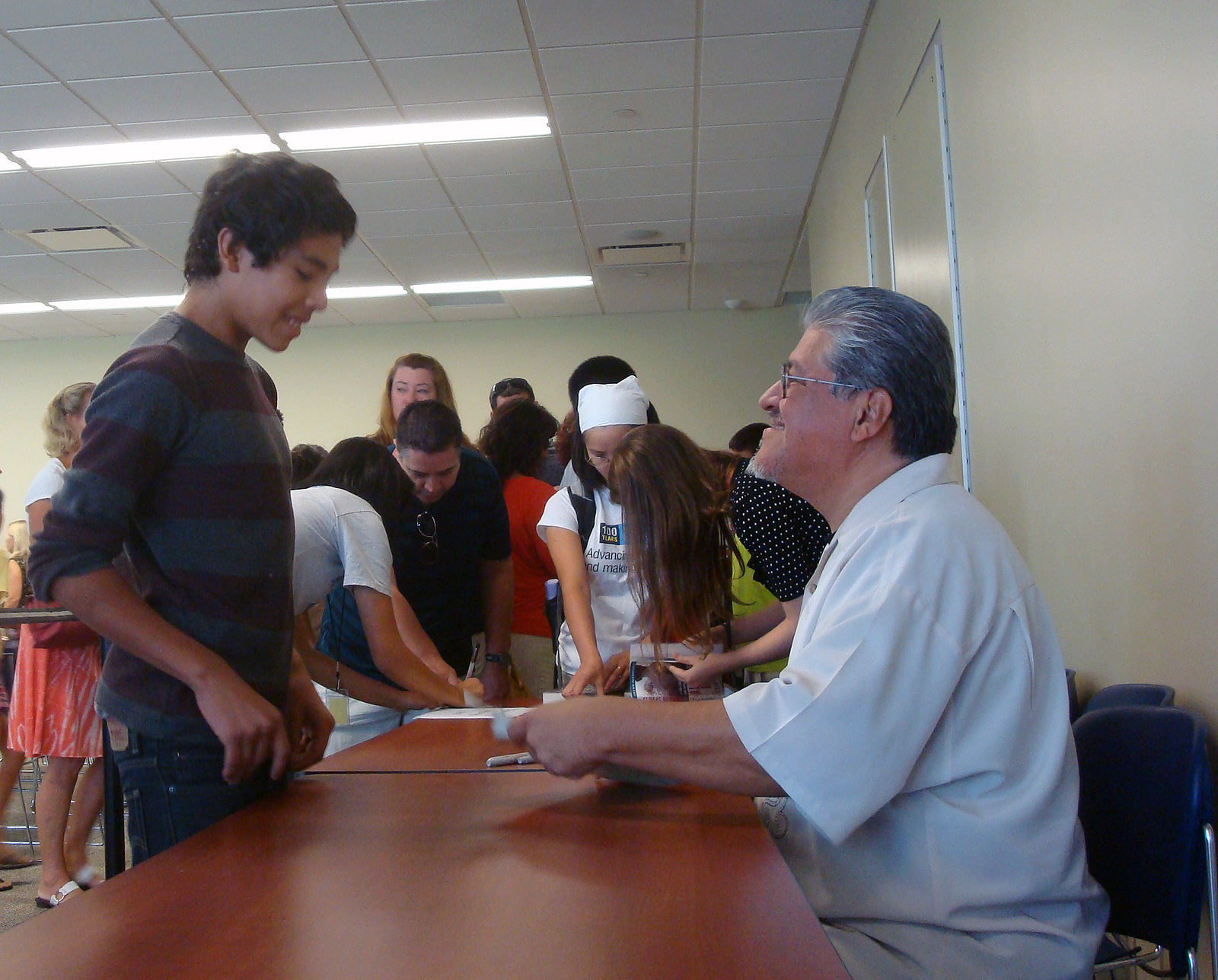

In Pakistan, September 21, 2012, was marked as a day of remembrance for Prophet Mohammad in response to a film that went viral and sparked violence in parts of North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Knowing that the time difference between Houston and Pakistan was ten hours, I began checking online Pakistani newspapers as soon as I awoke. By the end of twenty-four hours, more than twenty people had been killed and six cinema houses had been burned. Meanwhile, progressive and secular communities that formed Pakistan’s majority were posting comments asking why extremists weren’t using their energies to offer help to the southern part of the country, where floods once again disrupted lives. As Sunday afternoon temperatures climbed toward triple digits, a large crowd gathered in the comfortable confines of the Fullerton Public Library’s new Community Room. Families, teachers, and high school and college students waited for the arrival of Luis Rodriguez, author of Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A. and director of

As Sunday afternoon temperatures climbed toward triple digits, a large crowd gathered in the comfortable confines of the Fullerton Public Library’s new Community Room. Families, teachers, and high school and college students waited for the arrival of Luis Rodriguez, author of Always Running: La Vida Loca, Gang Days in L.A. and director of