I Went to the Woods to Write: Dimitri Keriotis on Writing Fueled by Natural Settings

Dimitri Keriotis’s short story collection The Quiet Time is forthcoming this fall from Stephen F. Austin State University Press. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in the Beloit Fiction Journal, Flyway, BorderSenses, Evening Street Review, and other literary journals. He teaches English at Modesto Junior College and co-coordinates the High Sierra Institute. He and his family live in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

We’ve all heard Thoreau’s declaration, “I went to the woods to live deliberately….” Considering that Walden resulted, maybe he should have written, “I went to the woods to write deliberately….” Thoreau probably wasn’t the first whose writing was fueled by a natural setting, and he certainly wasn’t the last.

We’ve all heard Thoreau’s declaration, “I went to the woods to live deliberately….” Considering that Walden resulted, maybe he should have written, “I went to the woods to write deliberately….” Thoreau probably wasn’t the first whose writing was fueled by a natural setting, and he certainly wasn’t the last.

Years ago I was on the faculty for the Tahoe Wilderness Institute, a ten-day interdisciplinary program that took place largely in the backcountry. I taught the literature and creative writing portions. High above the Tahoe basin, I would witness the great influence the natural world can have on writing. During one session we discussed The Dharma Bums atop a peak not far from Matterhorn Peak, the mountain Kerouac wrote about, and then we wrote about the mountains in our lives. Those serious about mountaineering wrote about their favorite climbs; others delved into other mountains—divorce, alcoholism, rough childhoods. Following that session, some students bounded down the mountain a la Japhy Ryder from The Dharma Bums, while others quietly descended, lost in their own thoughts, most likely processing the words they’d written.

My time in Tahoe led me to teach workshop-based courses at the High Sierra Institute (HSI), a satellite campus of the Yosemite Community College District, at Baker Station, a 1930s field station owned by the U.S. Forest Service. While HSI isn’t in the backcountry, it’s in the middle of the Sierra Nevada far from serious civilization. The remote locale creates a setting devoid of distractions, including cell and internet services. Participants come to HSI and drop anchor, staying there (for free) during the duration of the course. Our lives become suspended as we enter three-day weekends of writing. HSI’s unplugged nature and the absence of personal responsibilities opens up mountains of time. We devote roughly ten hours a day to examining, discussing, producing, and sharing writing, all sprinkled throughout the day. The other time is spent taking siestas, sharing meals together, sitting next to the Stanislaus River or around the campfire, walking, reflecting. This kind of isolation and immersion, something few of us find in our regular lives, fuels our pursuits on the page.

My time in Tahoe led me to teach workshop-based courses at the High Sierra Institute (HSI), a satellite campus of the Yosemite Community College District, at Baker Station, a 1930s field station owned by the U.S. Forest Service. While HSI isn’t in the backcountry, it’s in the middle of the Sierra Nevada far from serious civilization. The remote locale creates a setting devoid of distractions, including cell and internet services. Participants come to HSI and drop anchor, staying there (for free) during the duration of the course. Our lives become suspended as we enter three-day weekends of writing. HSI’s unplugged nature and the absence of personal responsibilities opens up mountains of time. We devote roughly ten hours a day to examining, discussing, producing, and sharing writing, all sprinkled throughout the day. The other time is spent taking siestas, sharing meals together, sitting next to the Stanislaus River or around the campfire, walking, reflecting. This kind of isolation and immersion, something few of us find in our regular lives, fuels our pursuits on the page.

Every summer I see impressive writing emerge like magic. As much as I’d like to take credit for the prose produced, the setting has as much to do with the experience’s successes as anything else. We breathe the alpine air, hear the river’s running water, look up at mountains studded with granite boulders among towering pines, sit in a nearby meadow, and something shifts inside. A calming happens. It’s as if all that beauty takes hold of us and inspires us to be true to our stories, to be true to ourselves. It’s not uncommon for writers to explore narratives about deeply personal events that they’ve wanted to write about for years but have been unable to. And once one writer shares such a piece, which always happens, the others come forward, as if an impediment is dislodged, and important stories flow forth. This process produces a lovely level of trust among the group members, one that tacitly illustrates that this space and time are about creating and respecting our stories. While most share their work, I do not require that everyone do so except at the end for a final reading. My point is that while not required, everyone usually shares willingly because of the trust that results from the relaxed and accepting atmosphere created by the environment.

Every summer I see impressive writing emerge like magic. As much as I’d like to take credit for the prose produced, the setting has as much to do with the experience’s successes as anything else. We breathe the alpine air, hear the river’s running water, look up at mountains studded with granite boulders among towering pines, sit in a nearby meadow, and something shifts inside. A calming happens. It’s as if all that beauty takes hold of us and inspires us to be true to our stories, to be true to ourselves. It’s not uncommon for writers to explore narratives about deeply personal events that they’ve wanted to write about for years but have been unable to. And once one writer shares such a piece, which always happens, the others come forward, as if an impediment is dislodged, and important stories flow forth. This process produces a lovely level of trust among the group members, one that tacitly illustrates that this space and time are about creating and respecting our stories. While most share their work, I do not require that everyone do so except at the end for a final reading. My point is that while not required, everyone usually shares willingly because of the trust that results from the relaxed and accepting atmosphere created by the environment.

The rustic nature of the High Sierra Institute also contributes to the overall experience. The buildings are simple and hardly stand between us and the natural world. There’s a no-fluff factor up there, and that ultimately benefits us. While HSI has electricity, hot water, a fully functioning kitchen, and loaner laptops, these amenities provide enough comfort without pulling us away from our focus: writing. We don’t get yanked out of story mode via reality shows on cable or an unwelcome text or a happy hour with free peanuts. Small wonder that our free time usually involves casual talk about the experiences that have shaped our lives, which obviously lends itself to putting pen to paper.

Obviously HSI isn’t for every writer. Years ago I encouraged my friend Marquita to join us for a weekend of writing in the mountains. I showed her the colorful flier, convinced that she’d sign up in a heartbeat. She studied the flier, carefully examining the photographs of people sitting in a circle under a Jeffery Pine and of boulders alongside the river, her eyes moving all over them. Then she nearly flung it at me and said, “No way. Look at all the places where snakes are waiting to come out and bite you!” When I explained that no harmful snakes lived up there, she said, “Who cares? They’re still out there somewhere. The woods scare the hell out of me!” Fear doesn’t seem to make for a recipe for good writing, so HSI and Marquita aren’t a good match. But for others, getting away to a peaceful place in nature, wherever it might be, could be the medicine needed to write in ways we never imagined.

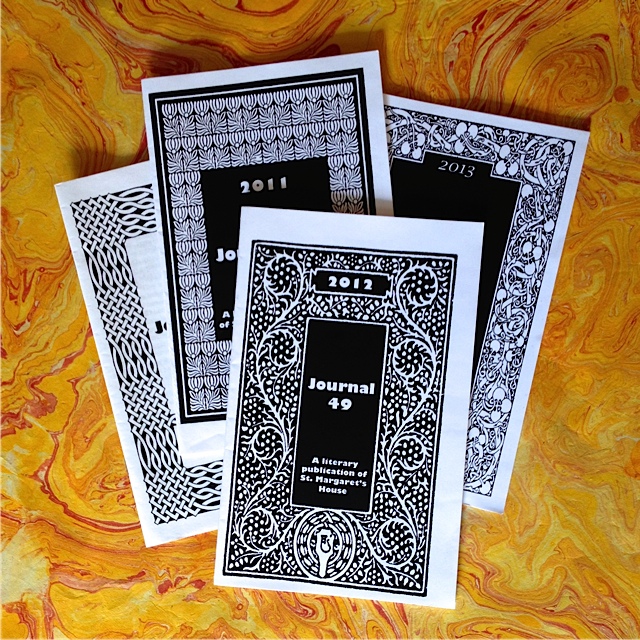

Top: Dimitri Keriotis. Credit: Ingrid Keriotis. Middle: A writing workshop in the mountains. Credit: Doug Higgins. Bottom: Writers sharing stories around the evening campfire. Credit: Doug Higgins.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.