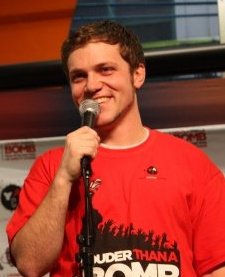

Tim Stafford on the Collaborative Side of Slam

P&W-supported poet Tim Stafford is a poet and public school teacher from Chicago. He is the editor of the classroom poetry anthology Learn Then Burn (Write Bloody Publishing). You can find him onstage at the Encyclopedia Show, the Louder Than a Bomb Poetry Festival, and in June throughout Denmark, Sweden, and Germany. In December, Stafford taught a workshop at Team Englewood High School in Chicago and facilitated the Riots on the Warp Land slam. We asked him to blog about the experience.  To some, Team Englewood High School on Chicago’s South Side seems like an unlikely gathering spot for over one hundred young poets. Englewood is a neighborhood that many folks view negatively, even though a large number of them have never stepped foot inside. The Riots on the Warp Land poetry slam, now in its third year, was created to bring awareness to some of the great things that people who live and work on the South Side are doing.

To some, Team Englewood High School on Chicago’s South Side seems like an unlikely gathering spot for over one hundred young poets. Englewood is a neighborhood that many folks view negatively, even though a large number of them have never stepped foot inside. The Riots on the Warp Land poetry slam, now in its third year, was created to bring awareness to some of the great things that people who live and work on the South Side are doing.

The Riots on the Warp Land (the title is borrowed from South Side poet Gwendolyn Brooks) is a regional prelude to the Louder Than a Bomb Teen (LTAB) poetry slam festival, a citywide event that occurs every February. The two events share a similar goal: get kids from all over the city together in a safe space to create and share their own stories.

The event’s founders, Dave Stieber, Stephanie Stieber, and Melissa Hughes, invited me to facilitate some of the bouts and help out with the group writing workshop. All three of the founders are public school teachers who wanted to create more poetry-based community-building outside of the LTAB festival.

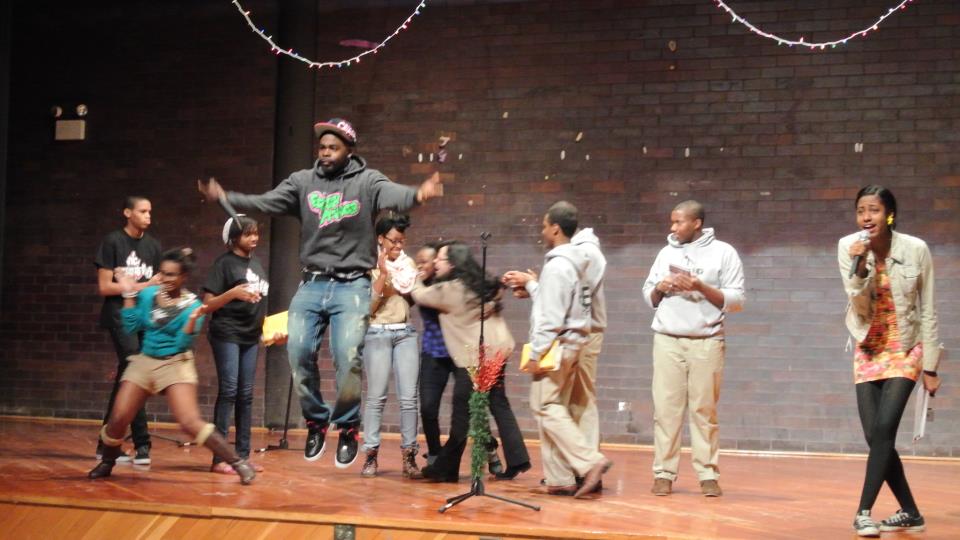

The event kicked off with an activity called “Crossing the Street,” in which kids on the fifteen teams split up into brand new groups. The groups got to work on prompts given by myself and teaching artists from Young Chicago Authors centering around identity, community, and neighborhoods. They created poems collaboratively. Before we started the actual “competition,” some groups presented their work to the crowd of about two hundred students and guests. The kids were familiar with the workshop model and were able to create some fascinating work despite the limited time. As far as the slam itself, there were three preliminary bouts, with the winner going to finals. I won’t go into detail about who won or who scored the highest. I, the promoters, and Young Chicago Authors don’t place emphasis on the competition, and we tell the kids that from the get-go. Writing and interaction are our goals. Calling it a poetry slam is our gimmick to get kids and community excited about poetry, which is why slam was invented.

As far as the slam itself, there were three preliminary bouts, with the winner going to finals. I won’t go into detail about who won or who scored the highest. I, the promoters, and Young Chicago Authors don’t place emphasis on the competition, and we tell the kids that from the get-go. Writing and interaction are our goals. Calling it a poetry slam is our gimmick to get kids and community excited about poetry, which is why slam was invented.

This is the second time I’ve been able to take part in this event, thanks to Poets & Writers. Seeing the progression in the quality of the written word from one year to the next is a humbling experience. The passion and attention to craft instilled by their teachers, coaches, and mentors is paying off in poetry that is mature beyond the years of its young writers. I look forward to seeing some of you next year at the fourth annual Riots on the Warp Lands.

Photos: Top: Tim Stafford. Bottom: The winning team is announced. Credit: Stephanie Stieber.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in Chicago is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from Poets & Writers' Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

What are your reading dos?

What are your reading dos?

What makes your organization and its programs unique?

What makes your organization and its programs unique?  How do you find and invite writers?

How do you find and invite writers?  What are your reading dos?

What are your reading dos? A poetry slam, we now know, has rules. Poems are orally presented, in front of a microphone. The poems must fit in a time slot of three minutes. Structure, rhyme, and meter are optional. Poets come to the front of the audience, one at a time, and deliver their work. Then the judges (there were five of us at the September slam) hold up cards ranging from one to ten, and fractions thereof. So, the poet might receive an 8.7 or a 9.3, a la Olympics. A time-/scorekeeper records the scores, discards the high and low, and averages the remainder.

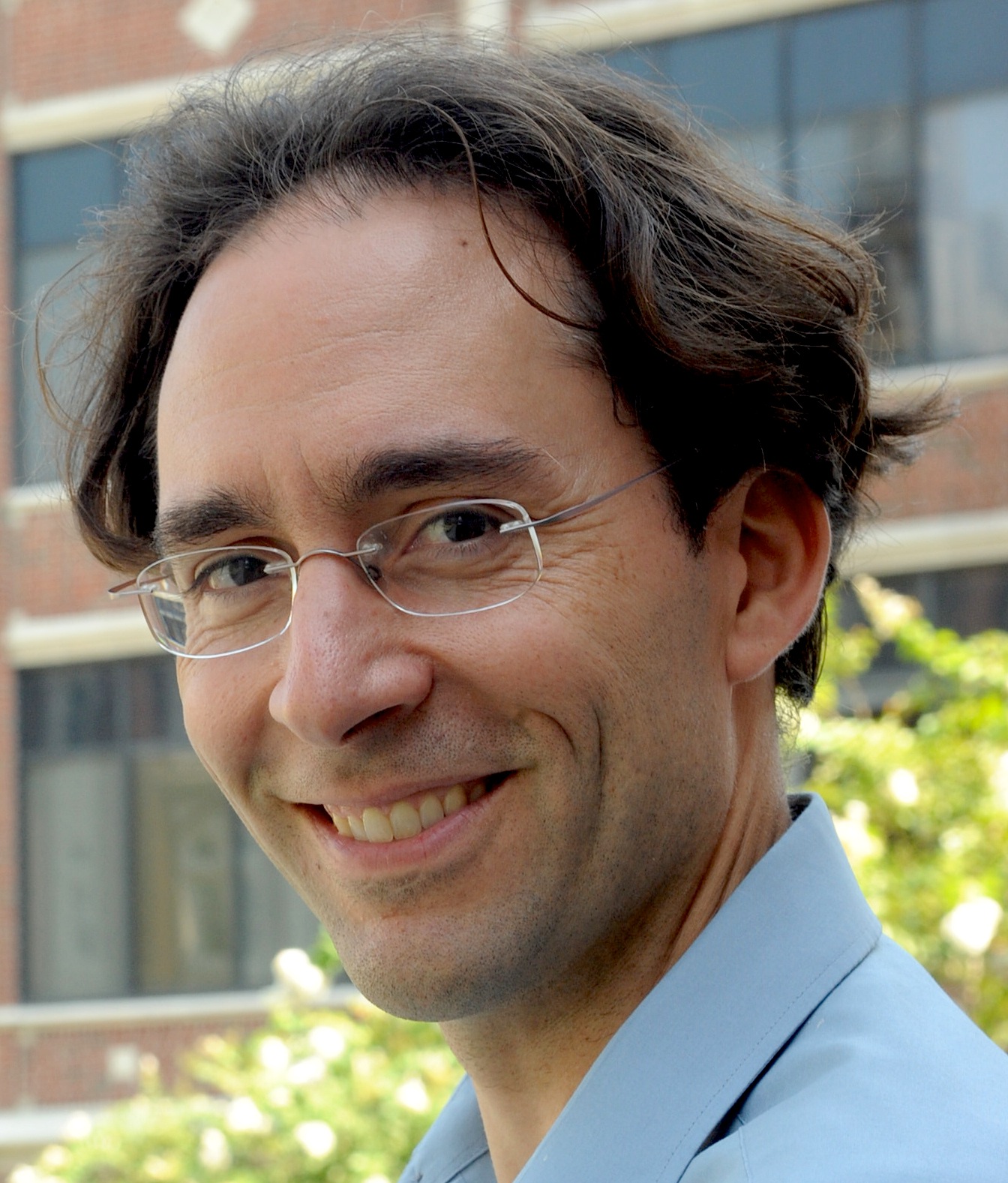

A poetry slam, we now know, has rules. Poems are orally presented, in front of a microphone. The poems must fit in a time slot of three minutes. Structure, rhyme, and meter are optional. Poets come to the front of the audience, one at a time, and deliver their work. Then the judges (there were five of us at the September slam) hold up cards ranging from one to ten, and fractions thereof. So, the poet might receive an 8.7 or a 9.3, a la Olympics. A time-/scorekeeper records the scores, discards the high and low, and averages the remainder. On October 1, 2012, Inprint, Inc., and the Poetry Society of America in association with Nuestra Palabra presented a panel discussion, Red, White & Blue: Poets on Politics, featuring Sandra Cisneros and Tony Hoagland and moderated by the Poetry Society’s executive director Alice Quinn. The gathering, held at the University of Houston, drew a mix of students and community members and there was a rich conversation about the urgency of poets to speak in response to social issues. Both Cisneros and Hoagland read work by poets they admire, followed by a discussion about the importance of giving voice to community. Sandra closed with a poem by

On October 1, 2012, Inprint, Inc., and the Poetry Society of America in association with Nuestra Palabra presented a panel discussion, Red, White & Blue: Poets on Politics, featuring Sandra Cisneros and Tony Hoagland and moderated by the Poetry Society’s executive director Alice Quinn. The gathering, held at the University of Houston, drew a mix of students and community members and there was a rich conversation about the urgency of poets to speak in response to social issues. Both Cisneros and Hoagland read work by poets they admire, followed by a discussion about the importance of giving voice to community. Sandra closed with a poem by  What makes your workshops unique?

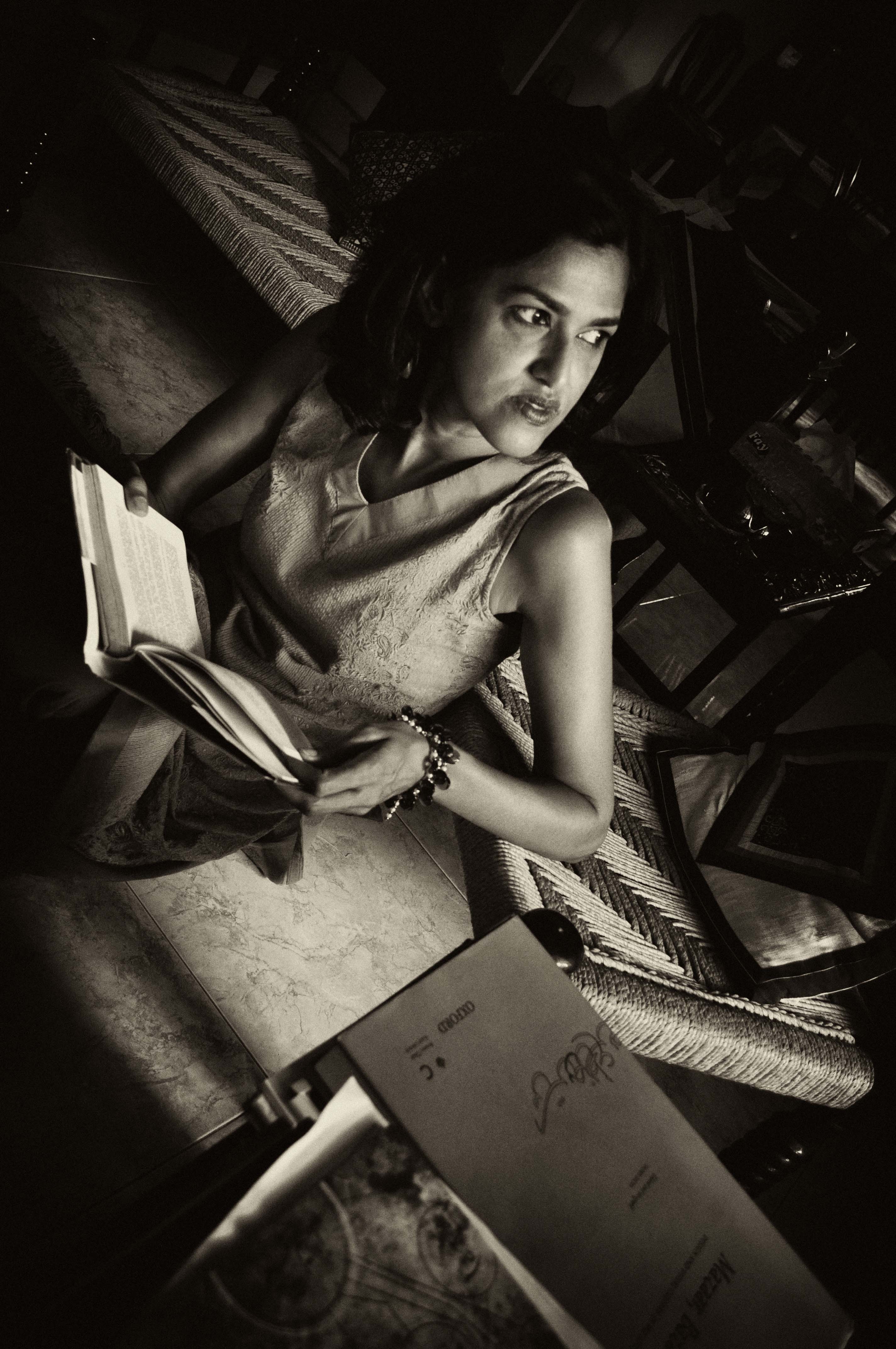

What makes your workshops unique? th teenagers, I wanted to work more with adults. So Shaista and I began planning a workshop that spoke to the rootless-ness we both felt, whether we were in Karachi, Houston, or somewhere else. Shaista and I dedicated much thought to our workshop title—just as VBB co-founders and I had spent time honing in on the right title for “our” organization three years earlier. We finally agreed on “Voices of the Displaced,” a title that rang true for us. It also attracted a pool of Houston-based writers who were born in other countries or elsewhere in the United States, who had come from communities of color, or identified themselves as GLBT/queer. Project Row Houses offered us a meeting space and co-sponsored the series. We sent out emails inviting people to join—VBB didn’t even have a website at that time. Our first group was intimate with only six participants, but over time, the group expanded. We always brought food and drinks and our gatherings offered formal writing but also a sense of community.

th teenagers, I wanted to work more with adults. So Shaista and I began planning a workshop that spoke to the rootless-ness we both felt, whether we were in Karachi, Houston, or somewhere else. Shaista and I dedicated much thought to our workshop title—just as VBB co-founders and I had spent time honing in on the right title for “our” organization three years earlier. We finally agreed on “Voices of the Displaced,” a title that rang true for us. It also attracted a pool of Houston-based writers who were born in other countries or elsewhere in the United States, who had come from communities of color, or identified themselves as GLBT/queer. Project Row Houses offered us a meeting space and co-sponsored the series. We sent out emails inviting people to join—VBB didn’t even have a website at that time. Our first group was intimate with only six participants, but over time, the group expanded. We always brought food and drinks and our gatherings offered formal writing but also a sense of community. In Pakistan, September 21, 2012, was marked as a day of remembrance for Prophet Mohammad in response to a film that went viral and sparked violence in parts of North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Knowing that the time difference between Houston and Pakistan was ten hours, I began checking online Pakistani newspapers as soon as I awoke. By the end of twenty-four hours, more than twenty people had been killed and six cinema houses had been burned. Meanwhile, progressive and secular communities that formed Pakistan’s majority were posting comments asking why extremists weren’t using their energies to offer help to the southern part of the country, where floods once again disrupted lives.

In Pakistan, September 21, 2012, was marked as a day of remembrance for Prophet Mohammad in response to a film that went viral and sparked violence in parts of North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. Knowing that the time difference between Houston and Pakistan was ten hours, I began checking online Pakistani newspapers as soon as I awoke. By the end of twenty-four hours, more than twenty people had been killed and six cinema houses had been burned. Meanwhile, progressive and secular communities that formed Pakistan’s majority were posting comments asking why extremists weren’t using their energies to offer help to the southern part of the country, where floods once again disrupted lives.