The Anti-Poem

"Poems are bullshit unless they are screamed, or howled, or thrown in your face." Spoken word artist Najee Omar performs his poem "The Anti-Poem (After Amiri Baraka)" in this video by All Def Poetry.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

"Poems are bullshit unless they are screamed, or howled, or thrown in your face." Spoken word artist Najee Omar performs his poem "The Anti-Poem (After Amiri Baraka)" in this video by All Def Poetry.

Go to your bookshelf and pick out one of your favorite books. It doesn't have to be a poetry collection—any book will do. Write down the first line and the last line of the book. Use the last line of the book as the first line of your poem. Then, write until the first line of the book makes sense to use as the end of your poem. Use the lines as guides for a start and finish, but give your poem a unique theme, different from the original book.

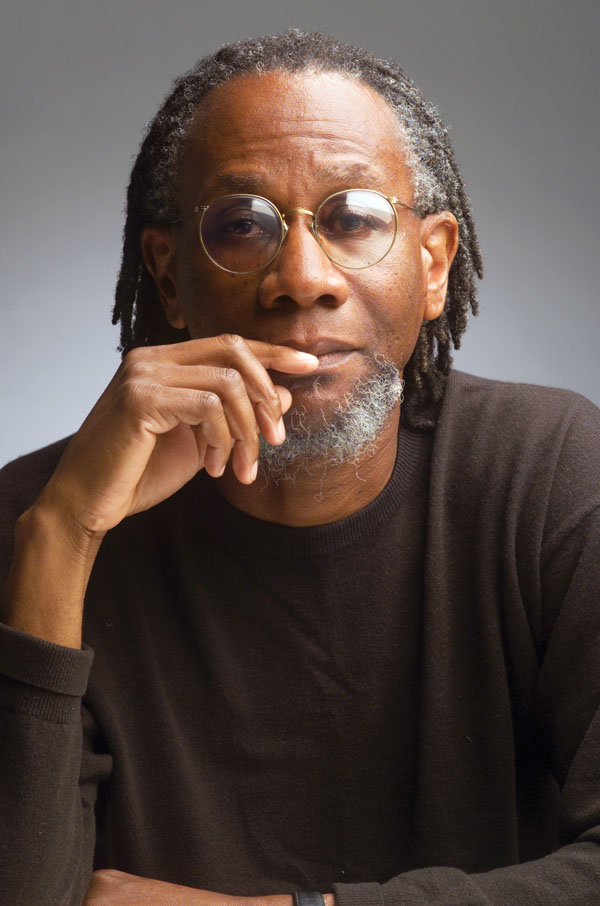

The Yale University Library announced today that Nathaniel Mackey has won the 2015 Bollingen Prize for American Poetry. The biennial prize of $150,000 is awarded to an American poet for the best book of poetry published during the previous two years, or for lifetime achievement in poetry.

The judging committee, which consisted of Al Filreis, Tracy K. Smith, and Elizabeth Willis, said of Mackey’s achievements: “Mackey’s decades-long serial work—Songs of the Andoumboulou and Mu—constitutes one of the most important poetic achievements of our time. Outer Pradesh—jazz-inflicted, outward-riding, passionately smart, open, and wise—beautifully continues this ongoing project.”

Mackey is the author of numerous books of prose, critical essays, and over a dozen poetry collections, including the National Book Award–winning Splay Anthem (New Directions, 2006), Nod House (New Directions, 2011), and most recently Outer Pradesh (Anomalous, 2014). In May 2014, Mackey was awarded the Poetry Foundation’s Ruth Lily Poetry Prize for lifetime achievement. Other awards and honors include the Whiting Writer’s Award, a 2010 Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Stephen Henderson Award from the African American Literature and Culture Society. Mackey has also served as chancellor for the Academy of American Poets. He teaches at Duke University.

Recent winners of the Bollingen Prize include Louise Glück, Gary Snyder, Adrienne Rich, Susan Howe, and Charles Wright. Established in 1948 by Paul Mellon, the prize is administered by Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library and has honored major American poets such as Ezra Pound, E.E. Cummings, Marianne Moore, and Wallace Stevens.

You can read a selection from Mackey’s collection Outer Pradesh at the Beinecke Library website.

Photo: Nathaniel Mackey (credit Nina Subin/New Directions)

Tung-Hui Hu is the author of three books of poetry, including Greenhouses, Lighthouses (Copper Canyon Press, 2013) and a forthcoming book on digital culture, A Prehistory of the Cloud (MIT Press, 2015). He is an assistant professor of English at the University of Michigan and a 2015 NEA fellow in literature.

I have an innate gift for making almost any situation awkward, particularly around writers and other celebrities. This makes me uniquely able to appreciate and receive awkwardness. After reading my poetry, I have sometimes been given tips on how to improve my readings for the future. I have watched excitedly as an audience member approaches me, and then asks for the location of the bathroom. It has not all been bad news, though; I think I have been propositioned a few times, but again—that awkwardness thing—I am not entirely sure.

But maybe awkwardness is another name for doing things differently, being able to walk through a door into a mysterious room where everyone is playing a card game and you don’t know the rules, but it doesn’t matter: you sit down anyway and play. Writers who work with hybrid genres or forms know what I am talking about. As I discovered in a recent P&W-sponsored reading at Wayne State University, younger writers have this sensibility, too.

Let me describe the scene for you: I walk into a Gothic Revival tower in Detroit and get in the classiest elevator I’ve ever seen. It’s noon. Wayne State was traditionally a commuter campus, so their events tend to be in the middle of the day, when more students are around. At a time when the boosters and the mortgage execs are having their power lunches downtown and downstairs, I find a room crowded with aspiring writers: some work in fiction, some nonfiction, but many, I learn, are simply undecided.

The English department has taken over the offices of the former Maccabees insurance company—with all this marble from the 1920s around us, it is enough to make anyone awkward. And yet, I am introduced in the same breath as the next person in the reading series, an actor from the TV show The Wire, which immediately makes the audience brighten up. It puts me at ease, too—for an hour, there’ll be no need to draw a line between serial TV versus poetry, or even fiction versus nonfiction. This is probably why, after I read a prose piece about an abandoned lighthouse, the students don’t bother to ask, “What is it?” Instead they ask: Where is the island, what did you see there, what did you find? Looking out the window, I realize the audience and I have found ourselves another island—this one of our own making, floating ten stories above Midtown Detroit.

Perhaps, in the way that an itch is a lesser version of pain, awkwardness is a smaller and even pleasurable version of discomfort: a signal, perhaps, that reveals something deeper about fitting in just enough, but not entirely. Perhaps this is what happens when you grow up a “model minority,” or when you think too much about what other people want—and you don’t quite give it to them. After years of practice, I still don’t know what awkwardness is, but I do know that poetry readings don’t come naturally to me. We have fun anyway. To R. A. in Mesa, Arizona, whose conversation with me after the reading was so engrossing that I signed and dedicated the book you bought, “For Tung-Hui Hu,” I’m sorry! I’ll buy you another copy.

Photo: Tung-Hui Hu. Photo Credit: Elizabeth Bruch

Support for Readings & Workshops events in Detroit, Michigan is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

A personal and in-depth look at the life and poetry of John Berryman, with particular focus on The Dream Songs.

"If you can dream—and not make dreams your master / If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim." This short film features Rudyard Kipling's poem "If," read by Tom O'Bedlam and filmed by Stephen Lister.

This week, the Northeast was pummeled by a sizable winter storm that accumulated many ominous names. This week, write a poem about an imaginary, absurdly catastrophic blizzard. You can call it whatever you like, but here are some suggestions to help guide you: "snowmageddon," "snowzilla," and the bone-chilling "snownado." What is special about this storm, giving it the potential to be the storm of the century?

Houston native and University of Texas Longhorn Gwendolyn Zepeda began her writing career on the web in 1997 as the first Latina blogger. Since that time, Zepeda has published three critically-acclaimed novels through Hachette and four award-winning children’s books, a short story collection, and two volumes of poetry through Arte Publico Press. She is Houston’s first poet laureate. Zepeda blogs about her P&W–supported University of Houston reading this past fall for Arte Publico Press.

A year and a half into my term as Houston’s first poet laureate, I’d been invited to give plenty of presentations about “being Houston’s first poet laureate.” For a recent reading at the University of Houston’s Honors College, however, the marketing department of Arte Publico Press asked me to put a new spin on it. They suggested I talk about growing up in the Sixth Ward (which was an impoverished area not known for producing novelists or poets), and then explain how I became a writer.

You know how, when figuring out how to explain your life to a stranger, you see your life from new angles? That was what happened to me as I prepared for this reading, several hours before it began. I typed an outline about my relatives who didn’t go to college but constantly read and told stories, the epistolary notes I passed in class, and the coveted bail bond office typewriter on which I typed my first poems. It occurred to me that art was the most exalted thing in my family, whether or not we all realized it.

You know how you worry, before each reading, whether anyone will actually attend? I always think of the Onion headline: "Author Promoting Book Gives It Her All Whether It's Just 3 People Or A Crowd Of 9 People." Happily, this reading was almost full in a room that seated fifty. There was a mix of people: students, professors, elderly alumni, a few of my friends. I was introduced to a dean and a women’s club.

You know how, with some audiences, you have immediate good chemistry? They’re in the mood to listen and there are good acoustics in the room, and you find yourself making eye contact with various faces, and it encourages you to be bold and witty and maybe read the piece you hadn’t planned on? That happened to me at this reading. There was a smiling, nodding young man who seemed to have grown up in a family similar to mine. There was a woman with shining eyes who seemed to be a writer herself. There were twentysomethings in the back who were obviously there for class credit, but who seemed pleasantly surprised. There was the dean, whose eyebrows rose at certain words and egged me on.

Afterwards, I signed books for readers, two of whom said they’d been following my work since I was only a blogger. I posed for photos with people who asked, holding my book so they’d later remember who I was. After that, I walked alongside my Arte Publico Press comrades as they rolled their equipment to the parking lot.

And after that, in my car, I reflected on the reading, my writing career so far, and my life in general. They were good thoughts. I was happy.

Photo: Gwendolyn Zepeda. Credit: Aleksander Micovic.

Support for Readings & Workshops events in Houston is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

"It can be warm and cold here at once." Poet Josh Lefkowitz recites a poem about New York City in a short film by Chris Follmer, which was a winner at the 2014 Rabbit Heart Poetry Film Festival.

There are certain words and phrases that are always used when discussing head colds, migraines, sprained ankles, and other ailments. This week, write a poem about an illness or injury without using the medical language commonly associated with it. For example, if you’re writing about a sinus infection, try avoiding the diagnostic terms “pressure” and “congestion,” and instead describe the symptoms using more metaphorical language. Have fun with it, like Ogden Nash did.