Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes

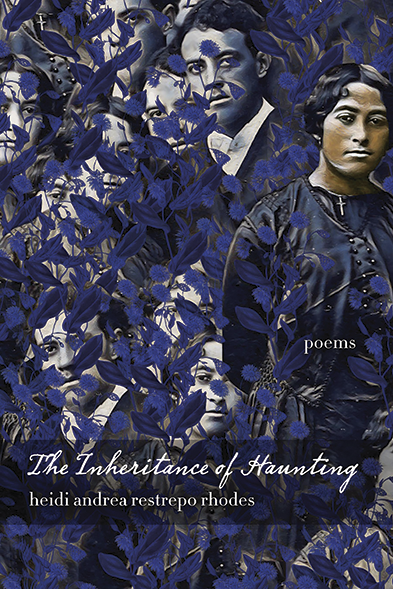

The Inheritance of Haunting

University of Notre Dame Press

(Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize)

these five hundred years in our bones

striated conquistas dragging

the letters of the harrowed tongue

into the geography

of our marrow, down

—from “prayer for the children who will be born with today’s daggers in their tomorrow eyes”

How it began: This book emerged as a result of poetry as a mode of survival and healing at the intersections of my own autoimmune illness and excavations into historical memory, generational trauma, and collective responsibility. I was undertaking familial genealogical research, as well as human rights research in militarized regions, while contending with illness that left me bedbound. Across the work, to be haunted is to live in an ongoing encounter with what will not let us rest, with what we face in the ongoing repetitions of violence in the afterlives of conquest, capital, coloniality. It felt necessary to write through some of the threads that intertwine our bodies with the world, with the political, with historical grief—to respond to the ghost as both the obstinate echo, as well as a willful, living fury calling us into question.

Inspiration: Family stories and ephemera passed down, prophetic dreams and how we carry our dead, colonial archives, histories of science, cultural mythologies and childhood legends, art and music and photography, monster studies, human rights reports and newspaper headlines, testimonies from survivors of state violence and authoritarian regimes. Jacques Derrida’s and Avery Gordon’s writings on haunting, and the film Rhymes for Young Ghouls. Saidiya Hartman’s work on the afterlife of slavery and critical fabulation. The awareness that my sadnesses are made up of the sadnesses of centuries. Somatic therapy, the Nueva canción movement, queer love.

Influences: Early on, I learned a lot about protest poetry from Agha Shahid Ali and Mahmoud Darwish: I find in their works a profound ability to document violence without spectacle, to bring me into the feel of the what else could be inside devastation and loss and various unfreedoms. Aracelis Girmay’s work has taught me a lot about wonder and intimacy inside of grief; close listening and cultivating familiarities; how to find the teeming universe in grain-of-sand moments. Aimé Césaire’s poetry gifts me with rule-breaking and the marvelous cacophony of anticolonial subversion—how poetry can do violence to the order of things.

Writer’s block remedy: I take walks or go to museums or read work by others—activities that draw me outward to listen and be in relation to the world around me, whether that be the sensory delight of pausing for a trail of flowers, or taking in new ideas through an art exhibition…things that will open me up in unexpected ways or transform me with a question or experience. I see writing itself as a process of transformation—of self, of reader, of the world. The impasse is prelude, inviting me to become something other than what I’ve ever been before. Transfiguration, metamorphosis, and translation (trasladar, other-siding ourselves) are called for at the impasse, and are conditions for traversing the moment between when the pen gets caught in stillness and begins to flow again.

Advice: Writing an abstract that articulates what the collection is about can help to communicate your work to editors while allowing you to create a map for what else your manuscript is asking to become. Take time to study presses and what they do, and ask others about their experiences with their presses. Seek advising and mentorship when things feel foggy. Submit, submit, submit. And don’t give up: Learn to know in your bones how much your stories matter.

Finding time to write: Given my schedule this year, I am insisting for myself that no matter what else I am in the midst of, I take at least two days a month to write poetry. Often things will come to me in dreams or in that space between sleep and waking, as if something (in me? outside of me?) is also insisting that no matter what, the writing must happen. And I also don’t only think of writing as a literal activity—there are ways we write or pre-write even if there is no page in front of us: Our bodies are writing our days; our thinking and feeling is writing before and through and after the writing. If we tune into that, we are making much more time for writing than we might otherwise assume. And then it is a matter of carving out spacetime to listen to what is wanted in the page.

Putting the book together: The book is divided into two parts, each moving through different kinds of ancestral memory, historical wound, and individual and collective modes of survival and flight. “El Otro Lado/The Other Side” winds through pieces of my family history in Colombia and the United States, reflecting our existence as a constellatory effect of histories of colonizers and colonized, violent and violated life haunting our present. “Casi Pájaros/Almost Birds” draws more on my human-rights work in different places contending with militarized atrocities; it relates a collective global haunted present in the afterlife of racial capitalism and traces a political inheritance that calls for response to material and symbolic violence. The two sections are meant to speak to each other, to convey the intertwining of individual and collective historical trauma and memory, as well as the forms of mourning, care labor, memory-work, imaginal endeavor, and political life necessary for healing.

What’s next: I am working hard on finishing my dissertation on settler colonialism and futurity in Colombia. As for poetry, I have begun writing my second collection while also trying to develop a generative workshop on queer science, and another on speculative memory. The Inheritance of Haunting took me through so much bone-deep grief; I’ve been coming up for air in the last couple of years, holding close the necessity of joy-work, of nourishing the imaginative and strange, of intimacy and love. And while none of that means the sadness has dissipated, I am interested in writing that senses more of the possible, and that, despite and through so much death and ongoing struggle, reaches for what it is to bring one another to life.

Age: 38.

Residence: Brooklyn, New York.

Job: I am finishing up my PhD in political theory and want to teach interdisciplinary classes in feminist theory, decolonial studies, Black and Indigenous thought, aesthetics, politics, philosophy, and writing poetry.

Time spent writing the book: Three years. The book was mostly written between 2012 and 2015, while I was bedbound from illness.

Time spent finding a home for it: Raspa, a queer Latinx journal and press founded by César Ramos, had invited me to publish a chapbook version of the book in 2014, but a whole confluence of things for which no one was to blame kept that from happening. I continued to build the manuscript, which came together in its current form at the end of 2017, and submitted it to the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize. It was my sister, Chelsea, who dropped it at the post office, as I was too sick to leave my apartment the week of the deadline, so I have her to thank for that solidarity in getting the manuscript out. In May 2018 I got a very generous and kind phone call from Ada Limón, who told me she’d chosen my work for the prize, and everything unfolded from there with University of Notre Dame Press. It was such a dream come true; I was pinching myself for months.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Marwa Helal’s Invasive species (Nightboat Books), Gala Mukomolova’s Without Protection (Coffee House Press), and Jake Skeets’s Eyes Bottle Dark With a Mouthful of Flowers (Milkweed Editions). Enjoyed is an understatement. Reading those three was really more a series of devastations, of openings in the face of wreckage.

![]()

Keith S. Wilson

Fieldnotes on Ordinary Love

Copper Canyon Press

You bankrupt the sun, underwater

statue. Dark galaxy of faults, our bed

a garden of the littlest sighs

of our waking. Our room, abstract.

Our body heat in space, the condensation

as the light makes heaven of it.

—from “Aubade to Collapsed Star”

How it began: At Callaloo, Gregory Pardlo challenged us to write the hardest poem we could write. So I started writing about love, which became heartbreak. And because of what’s happening on the news, that also became heartbreak for the world. I wanted to write through it. I wanted to live, and through writing I have.

Inspiration: I’ve always been indiscriminate about art: I would read either The Invisible Man by Wells or Invisible Man by Ellison. Comic books or video games or modernist art—nothing is more inspiring to me than someone who loves something so much that they can’t help but sing with it. It isn’t even wholly about talent. Passion is inspiring. It can be someone talking, if they do it with love.

Influences: Claudia Rankine changed everything from the kind of subject matter poetry could handle and the confidence with which you say what you feel directly to seeing any moment become extraordinary with the right context and structure. Gwendolyn Brooks is masterful with form and sound, and I’m influenced by her life outside of her poems—she was an extraordinary human being. Frank X Walker who believed in me and gave me the tools to believe in my poetry. Lucille Clifton, whose poems are perfect.

Writer’s block remedy: Time. They say time heals all wounds, which is a lie, but it is true that no wound healed without time. I hope that given enough time, I will come to an epiphany, or someone will happen to teach me just the right something, or I’ll learn to let go. It used to be harder. Now I have enough poems I’m waiting for that I’m much less afraid of famine.

Advice: Being published is a call someone else makes. It’s hard to know what to do to please others, and it’s maybe contrary to the place your poetry comes from. But someone’s first book changed you. Know that there are people waiting for yours.

Finding time to write: I make it an unquestioned part of my day, like brushing my teeth. There’s no day that becomes so busy you can’t find a moment to brush your teeth, because it’s everything else that finds a way to fit. Some days I only write a moment, but it adds up.

Putting the book together: Intuition and a series of broken systems. The same way I wrote them. There are a lot of love poems, but also a lot of poems about race and gender and justice and outer space and Greek mythology. I didn’t want someone to open the book and assume it was singularly any one of those things, so I color-coded the poems by theme and then arranged them by emotional intensity and tried to maintain a variance of color. I’ll never quite be able to explain it. I could barely fully feel it when it was happening.

What’s next: I’ve been experimenting with incorporating graphic design and visual elements into my work. Today we largely receive poetry through visual media: books and journals and websites. Like, it’s important to see the line breaks because often you wouldn’t hear them. Or how the white space between stanzas and between margins changes how a poem feels, changes the speed we read it. I want to push that. As far I can get it. I’m writing comics and lyric essays too. And video games. Interactive fiction.

Age: 36.

Residence: Chicago.

Job: Adjunct professor at Spalding University and writing and design contract work in video games.

Time spent writing the book: Sometimes I’ll write the same poem dozens of times before I feel like one of those drafts is the poem, or I’ll take lines from finished poems and make a new one. It’s like the ship of Theseus: It’s impossible for me to figure out when anything really started. But the earliest publication in the book, “The Lost Quatrain of the Ballad of a Red Field,” was published in Tidal Basin Review in 2010.

Time spent finding a home for it: I’ve been trying since I was sixteen, but I got real serious about it ten years ago. I was so used to getting generic rejection letters! A week after I had decided to scrap the entire book again, I got a voice mail from Michael Wiegers. As I was calling him back I remember thinking, “They definitely already rejected me, didn’t they?”

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Library of Small Catastrophes (Copper Canyon Press) by Alison C. Rollins and Brother Bullet (University of Arizona Press) by Casandra López. Go out and get both of them!

Dana Isokawa is the senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.

(Portraits by Eugene Smith)