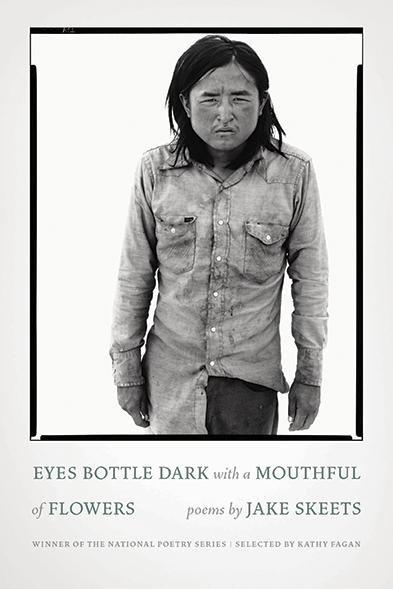

Jake Skeets

Eyes Bottle Dark With a Mouthful of Flowers

Milkweed Editions

(National Poetry Series)

the closest men become is when they are covered in blood

or nothing at all

—from “Naked”

How it began: It started with the body. The learning of desire prompted many of the poems in the early versions of the manuscript. My life shifted when I moved back home to the reservation. I noticed that the fields that surround Gallup, New Mexico, where I first experienced desire during summers and winters home, were also fields where other men would lose their lives. I also returned to the portrait of my uncle—a photograph Richard Avedon took of him in 1979—that is on the cover of the book. I began excavating the layers that exist in the narrative and violence of Gallup. Suddenly the fields that surround Gallup became a place for reflection, both in the collection and in my real life. I knew I had to write this book and poetry was the only way to tell it.

Inspiration: First, the land. The other day I noticed how quickly smoke from nearby forest fires can be cleared out by strong winds. Second, the way my mom and dad tell stories. They are the best storytellers. Third, the Black Mountain poets. Finally, all the other Diné poets.

Influences: Sherwin Bitsui because his type of thinking is so uniquely tied to the land and our community on the Navajo Nation. His mentorship guided me so much during the completion of my collection. Orlando White because he is a great thinker in terms of language and the idea of moving poetry away from just expression. He taught me to approach poetry through language, and I learned so much about craft from that shift. Joan Kane because her use of the lyric is so beautiful. I am floored reading just one line from her poems, and that’s what I want to accomplish in my work: one-line moments when the poem leaps from the page. Finally, Santee Frazier because his understanding of sound influenced much of my attention to sound.

Writer’s block remedy: I turn to craft. I turn to experimentation. If I am stuck on a particular image or trigger, I will give myself rules to compose a poem. I will use random word generators or word scramblers online. I give myself prompts that force me away from the left margin. I try to approach the poem through its language. This work and energy is a way to honor language and honor the image or trigger that inspired the poem. This communication with poetry is what keeps me carving through the white space until a poem is left.

Advice: In the words of my mentor Sherwin Bitsui, carry your manuscript everywhere with you.

Finding time to write: I don’t, which may be a crime to admit. If you’re in a circumstance with an end date, an MFA for instance, I understand the need to carve out writing time. During my MFA, I worked full-time, so I found time to write during my commute. I was very close to listing the Phoenix public transit system in my book acknowledgements because I finalized the first part of the collection in railcars and buses. Otherwise, it was small moments like waiting in a movie theater or waiting at the bar in a club. Now I am simply allowing myself to breathe. The collection took much to write. However, I do still find moments to write, and it’s often on drives. Residing on a reservation often means driving miles for daily needs. I get to experience so much on these drives in terms of image, time, and sound. Often, a poem finds its way through.

Putting the book together: I used a variety of approaches to order the book. I knew I needed something familiar for the reader to grasp within the collection. For me, that became time. The linear coming-of-age, coming-out timeline is that field where the reader can find footing to wade through the collection. Finding the poems’ order within that timeline took many exercises that I learned from the Institute of American Indian Arts. These exercises included traditional ones like hanging poems on a wall and recording myself reading the manuscript. Others included carrying the manuscript everywhere, hiking while reading the poem out loud, or hiking while listening to a self-recording of the manuscript.

In the beginning I thought I was writing a collection about coming out and desire. However, midway I moved back home to the reservation and everything shifted. I saw the face and portrait of my uncle in the faces I saw everyday traveling to Gallup. I realized I couldn’t separate my queerness from the violence that occurred around me. So I started the collection again, this time on the border between my reservation and the outside world, the border between masculinity and sexuality, the border between beauty and brutality, and the border between the body and the land.

What’s next: I am simply writing poems. I have written a few essays about the book and my poetics. My poems now have been revolving around the code used by Navajo Code Talkers during World War II, the idea of Diné love and Diné joy, and the many forest fires, diminishing water wells, and abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation.

Age: 27.

Residence: Tsaile, Arizona.

Job: English faculty at Diné College.

Time spent writing the book: Some of the earliest images and lines are from high school poems I have kept with me. Other poems and lines were born from my undergraduate years at the University of New Mexico. Conceptually, I would say the book has been simmering within me for about a decade. Physically, the manuscript took about three years to compose, revise, order, and revise again for publication.

Time spent finding a home for it: I submitted the collection to several prizes before I heard from the National Poetry Series. I am very fortunate that the book was published only a year after finishing my MFA.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Library of Small Catastrophes (Copper Canyon Press) by Alison C. Rollins, Refugia (University of Nevada Press) by Kyce Bello, The Milk Hours (Milkweed Editions) by John James, The People’s Field (Southeast Missouri State University Press) by Haesong Kwon, Bodega (Milkweed Editions) by Su Hwang, Documents (BOA Editions) by Jan-Henry Gray, and The Last Visit (Autumn House Press) by Chad Abushanab.

![]()

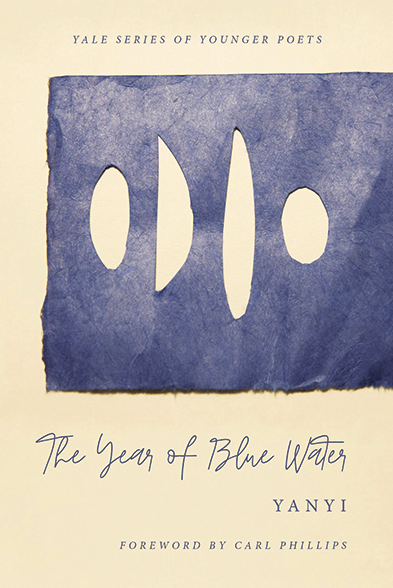

Yanyi

The Year of Blue Water

Yale University Press

(Yale Series of Younger Poets)

It is a certain life and not its answer that is worthy of being repeated. Invitation, invocation, request.

—an excerpt of The Year of Blue Water

How it began: A series of events forced me into a major emotional reckoning. I was barely able to go through the motions of everyday life anymore. So, the urgency of being present with myself and my body. And the will to be alive on my own terms.

Inspiration: Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts showed me that an integrated self was possible in writing. Aldrin Valdez’s poem “Shuffled Slides of a Changing Painting (After Robert Gober),” numbered like Nelson’s Bluets, was crucial to my understanding the technical power of a poem out of, and still in, order. And of course the person who told me to start the notebook, who learned that from Carolyn Forché.

It’s funny to think about what we’re inspired by: So much is timing with who we are as artists. People have compared the book to Bluets a lot. But though I had read it before, I had gotten Bluets mediated through Valdez. I finally met Carolyn Forché this past fall. We did, indeed, have a conversation about notebooks. But only after the fact. “Original” is an adjective—it describes an experience of relative origin.

Influences: Susan Sontag: passion. Agnes Martin: repetition, solitude. Linda Gregg: not understanding. Robin Coste Lewis: gathering, taking time for what is worth saying.

Writer’s block remedy: I read recently in an advice column that time is not what heals relationships: It is that things happen in time. I don’t see silence as an impasse. I work to be available to writing when it arrives. In silence I focus my erotic energy on my relationship with the world. I work on eating, sleeping, feeling, and enjoying my life. I read. I allow myself to change. The writing comes to me when there is something to say.

Advice: I’ve found that it is more important to love your own book than getting it published. I mean the kind of nourishing love you feel when you read the poetry you admire. This is the love that will help you edit it. It will help you advocate for it and send it out again and maybe one day read it over and over as though it is still new to you. Because it should be. Become your own reader and someone else will read it too.

Finding time to write: I now have the fortunate problem of figuring out when I should write versus when I can. When I was working I read and wrote early mornings, evenings, and all day during the weekends—any time I had a thought and a snatch of time (commuting, in line, walking somewhere, etc). I did not like it. It is a writing for survival, not choice. I don’t take for granted the depth of thinking I can choose in my writing now.

Putting the book together: I went through every note I had written and formatted them on individual pages, then printed out the pile. Then I would take, oh, three hours and find the one that felt like a beginning, then read again until there was another poem that felt right in following. In subsequent drafts I would reread the last manuscript and change things as I got bored or uneasy while reading. Lather, rinse, repeat with two-month breaks in between. I did not analyze or outline. The accumulating effect and the thematic overlaps were not apparent to me until the book was completed. It was an emotional and intuitive process. Even the breaks I didn’t time: I just noticed after a while, looking at the dates of my drafts, that I felt ready to reread the manuscript every two months.

What’s next: I’ve been writing love poems and thinking a lot about intimacy. I’m at the end of a second manuscript and have started a new pile for a third—it’s too early to say what that will be in its final stages, but it seems my interest in intimacy was too large for one manuscript. In between, I’ve been writing short pieces of criticism, a verse play, and a larger critical project on politics, poetry, and aesthetics, with a focus on fascism in modernism and all the threads that come to and from that.

Age: 28.

Residence: Jersey City.

Job: I worked for several years as a software engineer and am now exploring life as a full-time student and writer.

Time spent writing the book: About eight months, then two years of editing until I handed it in to Yale.

Time spent finding a home for it: About a year, and I am lucky for it. I benefited from the long, hermetic editing process, encouragement from friends who read it, and every reader who could meet the work where it was.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: To be perfectly honest, I haven’t been reading very much in this century. I have accepted that I will always be somewhat out of sync. This year I’ve savored Linda Gregg and Jack Gilbert’s discographies and am recently admiring Agha Shahid Ali’s. Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s To the Place of Trumpets (Yale University Press, 1988) and Lydia Davis’s The Thirteenth Woman and Other Stories (Living Hand, 1976) are up there for best debuts I read this year.