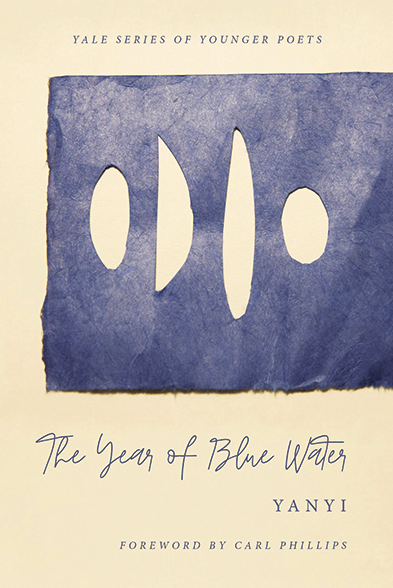

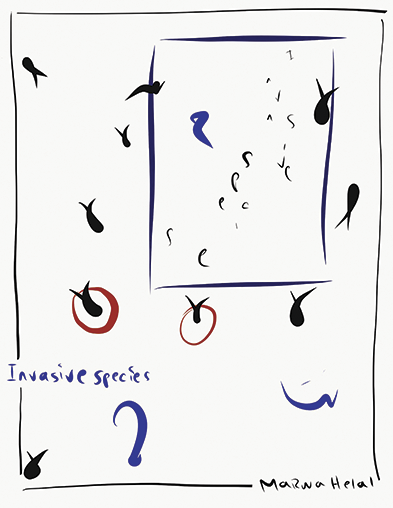

For our fifteenth annual look at debut poetry, we chose ten poets whose first books struck us with their formal imagination, distinctive language, and deep attention to the world. The books, all published in 2019, inhabit a range of poetic modes. There is Keith S. Wilson’s reimagining of traditional forms in Fieldnotes on Ordinary Love, and Maya Phillips’s modern epic, Erou. There is Maya C. Popa’s lyric investigations in American Faith, Marwa Helal’s subversive documentary poems in Invasive species, and Yanyi’s series of prose poems in The Year of Blue Water. The ten collections clarify and play with all kinds of language—the language of the news, of love, of politics, of philosophy, of family, of place—and, as Popa says, they “slow and suspend the moment, allowing a more nuanced examination of what otherwise flows through us quickly.”

While the books share a sense of urgency and timeliness, in fact these collections got their starts years, even decades ago. So we asked each of the poets to share the stories behind their debuts—what experiences or scraps of language incited the book’s first poems and what insight pulled them through the process of writing and publishing a collection.

Many of the poets described accepting the time it takes for poems to arrive and learning that making poetry doesn’t always entail sitting at the desk, pen in hand. “If I am looking at the world through poetic lenses and thinking of all of my work through the lens poetry has gifted me, then the poems are being written and will touch the page when it is time,” says Camonghne Felix. Sara Borjas reminds herself that everyday activities like reading and cooking are also “a making.”

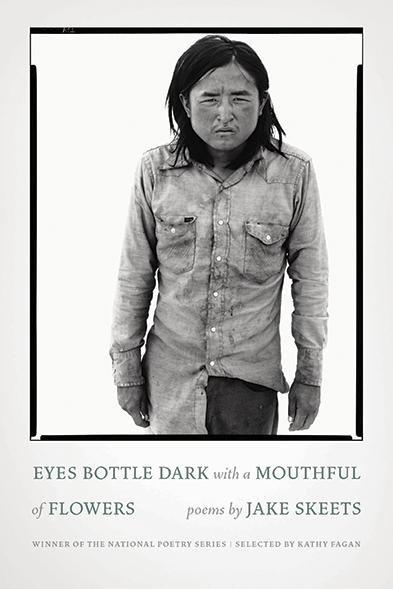

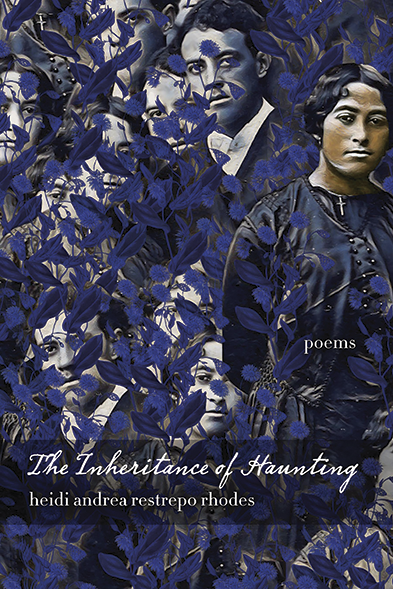

Several of the poets also said their books began when they wrote through their original subject to its opposite or counter. In writing about Blackness, Felix wrote about survival but also thriving. Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes took on the ghost as “both the obstinate echo, as well as a willful, living fury calling us into question.” Jake Skeets wrote about the fields of Gallup, New Mexico, as a site of both desire and violence; Patty Crane found inspiration in beauty, but also the suffering and injustice that brings it into relief.

And all the poets credit the people who helped them along the way—friends who pored over drafts, editors who challenged them to be better, mentors who encouraged and advised, family members who offered support. All the people who remind us that behind every book is a poet, and behind every poet is a community—or as Crane says, “the threads that bind us to one another and to the world.” So we hope that when we lift up these poets and their collections, it is also a testament to the communities that stand behind them as artists and nurture them far beyond the pages of a book.

Patty Crane, Camonghne Felix

Jake Skeets, Yanyi

Marwa Helal, Maya C. Popa

Sara Borjas, Maya Phillips

Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes, Keith S. Wilson

pw_crane_final_phr.png

Patty Crane

Bell I Wake To

Zone 3 Press

(First Book Award for Poetry)

as if desire is a kind of blindness

that listening unveils

—from “Frogsong”

How it began: I didn’t set out to write a book. I set out to write the poems that came to me and compelled me to keep writing. Poem by poem, that writing was mainly driven by my daily life, the awarenesses unfolding from my roles as a woman, a mother, a friend, a citizen of a community, a country, and the earth—all the threads that bind us to one another and to the world, however tenuous and ephemeral. At some point I had a critical mass of poems and was eager to explore ways to connect them.

Inspiration: My richest sources of inspiration stem from my deepest connections. Rich because they’re deep. Deep because they require tending. My family and loved ones, especially my incredible daughters, who I once carried in my body and now carry at all times in my consciousness. My home and place, especially the natural world that surrounds me and informs how I live, work, and relate to the world. My translating, which allows me to inhabit another speaker and be the author of poems I did not write, their temporary surrogate and shepherd. My fellow artists—being around them, experiencing their work and inspirations. Beauty catches my eye everywhere, and everywhere its edges are defined, even heightened, by injustice and suffering, as if they’re beauty’s very outline—the way the dark shadings around [Giorgio] Morandi’s bottles suggest the power of the unseen. They’re what bring the bottles into relief, defining them as bottles.

Influences: The following are poets whose work I’ve read closely, sometimes with great difficulty, and through that close reading experienced some new awareness that helped me think differently about my own work. Emily Dickinson for the enduring boldness of her poetry and vision, the sheer weight of each word, and how she possesses a moment, telling it “slant.” Elizabeth Bishop for the lyrical precision, calm authority, and descriptive brilliance of her writing. Jean Valentine for the quiet intimacy of her poems, distilled to an emotional essence that often defies narrative conventions. Tomas Tranströmer for the way he moves so freely between the everyday and liminal worlds that his poems seem to bubble up from the realms of what’s inexpressible.

Writer’s block remedy: If I find myself losing a staring contest with the blank page, I usually set a timer for twenty minutes, put my pen to the paper and write, stream-of-consciousness, until the timer goes off. This often helps me uncover a subject hidden in the weeds of distraction or overthinking and gets me back in the groove. I try to stay open to the possibility inherent in letting the mind’s reins go. What gets me going is the timer and zero pressure to write anything “worthy.” What keeps me going is the subject, if I find my way to it. If not, and if I can’t read my way back into writing, I switch my focus. I might work on revisions, translations, or other creative endeavors such as erasures, collages, drawing, or exploring and scrounging around in the woods. I’ve also learned that impasses can be crucial for revitalization.

Advice: Believe in the work, be patient, persist. Quiet all the voices except the inner one. Less is more. If you’re not sure whether the poem belongs in the collection, it probably doesn’t. Make the book the final poem. Submit the manuscript to presses whose publications you love. Keep moving forward, thinking about poems for the next book.

Finding time to write: I’m most successful finding time to write when I make the time by scheduling it. Which is to say, I treat writing like work. It is my work, my job. One of my jobs. I also need to say that, for me, having a devoted space to write is as important as finding the time. I’m fortunate enough to have a tiny, humble studio I helped build with my own hands. It’s tucked into a field that overlooks an active beaver pond. This quiet space with no internet or cell service offers its own form of time, where I can enter the writing quickly and be more focused, making the most of the few hours I can devote to my writing on most days.

Putting the book together: The manuscript went through so many iterations! It’s been twice as long, half as long, had three different titles, and included poems that clearly didn’t belong. I think I needed to discover what Bell I Wake To was by first understanding what it wasn’t. Also, at some point I realized I was letting the feedback of others overtake my own innate feelings and sense of the work. While the feedback was often helpful, even crucial, in the end I had to set the manuscript aside for a good long while to settle all those voices and tune back in to the patiently waiting inner one. Ultimately, I ripped the manuscript apart and started over, allowing the process to flow by simply letting the end of one poem influence my choice of the next without overthinking it. Honestly, it was as simple as trusting my choice. This may have been the most powerful lesson of putting together the book.

What’s next: Right now I’m actively sending out my second full-length collection, which was written during the three years I lived in Sweden. I’m also deep into translating the complete poetic works of Tomas Tranströmer. And I’ve been thinking and writing a fair amount about the growing disconnect between us humans and the natural world, the threats this disconnect poses, how being stewards of the natural world means stewarding humanity. I don’t know how or even if this preoccupation coheres in the poems, as it’s all still unfolding.

Age: 59.

Residence: Windsor, Massachusetts, and Craftsbury, Vermont.

Job: After a decades-long career as a registered nurse working in a variety of roles and settings—my undergraduate degree is in nursing, my master’s in creative writing—I’m now a literary translator, Swedish to English, and the president of a community-building nonprofit.

Time spent writing the book: About fifteen years. The buildup to writing them surely took far longer, probably my whole life. A good number of those fifteen years involved setting the poems aside and letting them steep, free from my meddling long enough that I could come back to them with fresh-eyed amnesia.

Time spent finding a home for it: I started sending out this version about a year ago. If you count other wildly different versions of the book, then ten years or so. In the latest round, it was rejected eight times and was a finalist twice before being selected by Zone 3 Press, whose editors are an absolute delight to work with and helped make Bell I Wake To a beautiful book.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: So many good debut books and wonderful presses, so little time! I’m excited about Space Struck (Sarabande Books) by Paige Lewis, Hail and Farewell (Perugia Press) by Abby E. Murray, and Bodega (Milkweed Editions) by Su Hwang.

![]()

Camonghne Felix

Build Yourself a Boat

Haymarket Books

No but wait you’re the water

—from “Willing in the Orisha”

How it began: In my MFA program at Bard, Ann Lauterbach asked me, “Are you representing or presenting?” And I wanted to see if I could present Blackness both in theory and in practice without performing it or decodifying it for the consumption of non-Black readers. I had to ask myself a series of questions that ultimately came down to one question—what is the project of Blackness? The answer I found was that Blackness is survival. And then that question led me to the question behind the entire book project—what goes beyond survival? What comes after it? What does it look like to depart from a journey of survival and enter a journey of thriving? The need to answer those questions is what compelled me to write the book.

Inspiration: The Black Arts movement, psychology, the way a good R&B album pushes at the edges of your spirit and makes you feel new things, In the Break by Fred Moten, the everyday joy of being a Black girl, the everyday trauma of being a Black girl.

Influences: Fred Moten, because he introduced a whole new framework by which to analyze the Black literary experience and the charge of “being” a writer. He also taught me that academic and artistic rigor is very much “a Black thing” and that has transformed my craftsmanship and my life. Mahogany L. Browne—my first mentor, my first teacher, the first authority figure I trusted to teach me what I didn’t know. My lyric is born from her lyric. Gregory Pardlo, who made me ask questions about my experience that helped me approach the stories I want to tell as an authority and not a bystander. Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon—learning from Lyrae and reading Lyrae opened up a whole new world for me in how to think and write about heartbreak and love. I write the best breakup poems now.

Writer’s block remedy: Two things. One, I learned from a Black studies professor at the community college I attended that there is no such thing as “being a genius” but that we all have a genius, and that your genius comes and goes on her own accord. She will eat when you feed her but will rest when she’d like. I turn to this thought when I am afraid that I’ll never write a good poem again, because it reminds me that the first poem wasn’t up to me and neither will the last one. And two, I remember that by living with intention I am in the process of writing poems. A poem or a series of poems may ruminate in your brain for days, weeks, months—and you may sit down four or five times to write it, but it won’t come until it’s ready. But if I am looking at the world through poetic lenses and thinking of all of my work through the lens poetry has gifted me, then the poems are being written and will touch the page when it is time.

Advice: You’ll never get another debut! Your first is your first. Fight for yourself, advocate for your project, and trust your community if they tell you it’s not ready.

Finding time to write: Lucky enough, it’s a core part of my everyday experience as a strategist. There’s never a day when I am not writing—and everything, even if it doesn’t look like it, is a poem.

Putting the book together: I spent half of the process building the ethos of the book and deciding which tools and techniques belonged in the toolbox of the book. That’s how I came to the footnotes and use of white space as an apparatus of silence. Once I had decided on those things, I built an outline, and just let it go. I wrote poems about everything and anything while keeping the ethos and the outline of the project in the back of my mind. Toward the end of the process I gathered all of the poems I wrote during that time and looked to see if there were any through lines that led me back to the project.

What’s next: Electing the first woman president of the United States, and my first prose novel.

Age: 27.

Residence: Boston—but I’m a proud and loud New York City native.

Job: I’m a political media strategist, currently working on the Warren for President team.

Time spent writing the book: I wrote all of the poems across a span of five years.

Time spent finding a home for it: Well, I didn’t worry too much about trying to find a publisher until people started asking me if I had a full-length book. I sent the project to some of the publishers who showed interest, and I originally signed with one press, but after an initial experience that raised red flags for me, I canceled the contract and pulled my book. It sat collecting dust for a year, and racked up accolades every time I submitted it to a first-book prize, still with no contract. When Haymarket reached out, I knew it was the right time and the right press, and I’m very glad I waited and didn’t let the pressure of publishing a first book take my eye off the prize, which is a book product I loved with a publisher I could trust.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Invasive species (Nightboat Books) by Marwa Helal, Hard Damage (University of Nebraska Press) by Aria Aber, and Brute (Graywolf Press) by Emily Skaja.