This year’s focus on debut poets features ten of the most notable first books of poetry published in 2018. The selected books, which encompass a broad range of styles and subjects, take on complicated and weighty topics—Fatimah Asghar’s If They Come for Us traces the impact of the Partition of India, Tacey M. Atsitty’s Rain Scald draws on Navajo ceremony to elegize and pray for the land, Mario Chard’s Land of Fire reckons with a sense of exile, and Tiana Clark’s I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood and Justin Phillip Reed’s Indecency contend with, among other issues, the injustices Black people have endured in America. Each poet seems to address the question Jenny George, author of The Dream of Reason, asks: “How much of our aliveness can we bear?”

For all the gravity of the poets’ concerns, though, there is also a sense of play and invention throughout their work. Asghar’s book contains poems written as riffs on Mad Libs and bingo grids and crossword puzzles, José Olivarez’s Citizen Illegal crackles with jokes, and Analicia Sotelo’s Virgin flashes with self-deprecating wit. When we asked the poets to describe the stories behind their books and how they work through writing impasses, many pointed to this balance between the serious and the playful. While writing his book, Olivarez says he wanted to tell stories with an “eye toward mischief.” Jenny Xie, author of Eye Level, says that when she reaches an impasse, it feels “completely necessary to lower the stakes, to restore some sense of play, or to build just for the sake of chasing a question, a sound, or the mind’s movements, wherever it leads.” Other poets describe it as the willingness to experiment—Clark discusses toying with different forms and syntax when she’s stuck—and other poets present it as daring: Diana Khoi Nguyen, author of Ghost Of, advises writers, “Dare to take on ambitious, large poetry projects that terrify you.”

Whether it’s through mischief or experimentation or rebellion, through anger or pain or the process of recovery, the ten poets featured here all seem to seek the freedom to write without expectation, to eradicate feelings of obligation, and to proceed with a sense of possibility. And this, after all, is what we hope for most from a debut book of poetry: that we might meet language spoken in ways we haven’t previously encountered, that we might, as Xie says, find “wilder forms.” And perhaps the work of these poets might inspire you to play with new forms and move, as George says, “without attachment in a purposeful direction toward what it is you don’t know.”

Tiana Clark, Jenny George

José Olivarez, Jenny Xie

Justin Phillip Reed, Analicia Sotelo

Diana Khoi Nguyen, Mario Chard

Tacey M. Atsitty, Fatimah Asghar

Tiana Clark

I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood

University of Pittsburgh Press

(Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize)

I think about patience and its stupid song.

I can’t wait— Yes, I’m always looking back.

at my dead.

—from “After Orpheus”

How it began: Survival. The seed of this collection is about poetry as a means of persistence, Black persistence: the extreme hyperbole of Black persistence itself, a tenacious ontological resolve, built and bred from struggle and resistance.

This collection emerged from my MFA thesis. However, after I graduated from my master’s program, I didn’t look at the book for four months. I needed a fallow season. I needed some voices to disappear. I am a deep people pleaser, and I lost my sense of control during the first draft of the book. So many edits were made to make my professors happy and to survive workshop. When I was finally ready to come back to the collection, I had clarity and freedom. I had learned to trust my own imagination again. The book revealed itself to me, and thousands of revisions ensued.

Inspiration: I’ll never forget the advice I received from Ross Gay when he visited Vanderbilt University for a reading and craft talk. I knew he had been a judge for several first-book contests, so I asked him what he looked for in a debut collection. He paused for a moment and said, “Broken shit.” He elaborated that he was interested in a collection that wasn’t highly curated but rather took great risks; even if some of the poems failed, he loved seeing new poets make magnificent attempts. My body slackened—and I took the deepest exhalation of my life. I’m paraphrasing his thoughts, but this notion that I didn’t have to have everything figured out provided a great sense of relief. It gave me permission to be audacious and messy with my work, to make mistakes, to risk making and breaking received forms, modulate my line breaks for speed and surprise, to split a sestina in tercets, to add air with caesuras to a sonnet, to reinterpret “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” as my own, to add another epigraph to a poem despite what anyone has to say about too many epigraphs and so on—I say to you: broken shit.

Influences: Terrance Hayes, Natasha Trethewey, Nina Simone, Sharon Olds, Li-Young Lee, e. e. cummings, Kendra DeColo, Geffrey Davis, Bill Brown, Kate Daniels, Danez Smith, Donika Kelly, Hanif Abdurraqib, Natalie Diaz, Elizabeth Bishop, Mark Jarman, Phillis Wheatley, Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, June Jordan, Robert Lowell, Robert Duncan, T. S. Eliot, Muriel Rukeyser, Rita Dove, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ross Gay, Ada Limón, Gabrielle Calvocoressi, Patricia Smith, Nikky Finney, Amiri Baraka, Kaveh Akbar, Dr. Houston A. Baker Jr., Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Fatimah Asghar, Louise Glück, Robert Hass, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, Arthur Mitchell, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Maggie Nelson, Claudia Rankine, Rihanna, Nella Larsen, Audre Lorde, Federico García Lorca, and the list goes on and on.

Writer’s block remedy: I allow myself to take a break. I don’t force myself to write when the poem is breaking down or dissolving. I pivot. I read, often in another genre. I listen to music, sometimes the same song over and over (for this collection, it was mostly Nina Simone’s “22nd Century”). I clean or cook; accomplishing a simple task helps me feel like I’m still moving forward, especially when I feel like I’m failing. I take a bath. I watch TV with pleasure and without guilt.

For me, it’s crucial to let my writing ferment often in darkness and without my incessant need to revise and fiddle and fix. After a few hours or days, I’m excited to meet the poem again like a long-distance lover. All this anticipation has built up, and I’ve forgotten what has annoyed me about this person—I mean poem, ha!

When I’m stuck I try to let my poems reveal themselves to me by experimenting with different containers. I will throw my poem in couplets, then tercets, or a ghazal. Sometimes I’ll employ what Carl Phillips calls the “grammatical mood” by changing tenses or adding a command or a question. With each costume change I’m weeding and slicing my syntax, and the poem can start to tell me what it wants from me. If I’m patient and attentive enough, the momentum of the poem swells and the shape starts to click into place like pushing down on matching puzzle pieces, satisfying.

Advice: Trust your imagination. Be on your own timetable. Ask yourself what you want out of this first-book process. Demand and determine your desires. Some advice from David Baker: “There is no hurry.” Some advice from my therapist: “Everything you want is not upstream.” Have a vision for your work before and after publication. Control your own narrative. Redefine what success means to you. Read or reread first books from your favorite poets. Write your own introduction to your collection. Ask a friend for their marketing questionnaire and fill it out. Trace your literary ancestry. Remember the last poem in your book is the entire book (I learned this from Nancy Reddy). Be kind to yourself and others. Keep submitting. Oh, and read this stunning excerpt from Heather Christle’s poem “Shelter in Place,” from the Harvard Review:

When you write a book you must not

forget to build a door you can use

to get out or else you will die there.

It is very exciting to make a new mistake.

Finding time to write: Due to teaching full-time and traveling for readings, I try to make the erratic and irregular nature of my schedule work for and not against me. For example, I often come up with poem ideas or lines in my car, so I’ll grab my phone and start recording. The major trick, for me, is to not only chase the impulse when it strikes, but to follow up on those notes whenever I can. My writing happens in a lot of intense bursts, so if an idea comes to me in the middle of a movie or during a conversation, I must stop and write it down. I’ve been woken up by a poem rattling through my body a few times too. I allow a new poem to take over my day, my weekend, all through the night when possible.

I also try to give myself buckets of grace when I feel I’m not writing enough. I remind myself that paying intense attention to the world is also writing. Revising is writing. Resting is writing. Loving myself through my failures is a way into writing. Defining my own relationship to writing is writing.

Putting the book together: It took me about a year to organize the collection. My amazing thesis director, Kate Daniels, gave me the idea for the title, which comes from a line in my poem “The Rime of Nina Simone.” Once she voiced the idea, the bones of the book coalesced in my mind. Instantly, I knew wanted to organize the manuscript as a triptych from the title:

“I Can’t Talk”

“About the Trees”

“Without the Blood.”

This triad structure helped to define the themes and movements of each section and to guide the flow of the book. From there, I decided to shape each section into its own thematic collection like three mini chapbooks.

I wanted to bookend the collection with two poems that dealt with a racial epithet being hurled at the speaker. I began with “Nashville” as the prologue poem because I wanted to set the tone with this frantic chase between Apollo and Daphne, coupled with the speaker feverishly searching the mob repeating, “Who said it? Who said it? Who said it?” The hunt for an answer is at the seam of every poem in this collection. I then chose to end the triptych book with my triptych poem “How to Find the Center of a Circle,” a poem that circles back to the origin of the speaker, as a child, being called a “n—” for the first time by two white boys on roller skates. The wound at the end is raw, yet permanent. The trauma is in the past—indelible—but always fresh in the speaker’s mind, a wound that resists healing.

After the structure was set, I commenced with the floor stage. I printed out every poem and spread them out on the floor, shuffled papers in each section until an order and pattern revealed itself to me like a giant Magic Eye picture. I read the intros and outros of each poem out loud like musical arrangements, and then I addressed aesthetic concerns. I often think about the eyes and ears of the reader. After a long poem, I want their eyes to rest on shorter poem, but I want to maintain a satisfying balance between fulfilling and thwarting expectations. I think of bookmaking as curating a new exhibit in a museum, as deciding how much access I want my readers to have to each poem. Some poems want to be touched, others have a ten-foot velvet rope.

What’s next: I am working on my second book of poems, which is invested in transcending pain and exploring length. I am fascinated with reading and writing long poems at the moment. I am trying to take up as much space as I need on the page and not apologize for myself.

Similarly, I’ve also begun to write essays. The dilation from poetry to prose—letting my mind unspool without compression—has been a wonderful surprise. I have a new essay out from Oxford American, an immersive homage about Nina Simone. I was fortunate enough to visit her birthplace in Tryon, North Carolina, and also conduct an oral history with my family who live nearby in Lenoir, North Carolina, reckoning with the damage that made me.

Age: 34.

Residence: Edwardsville, Illinois.

Job: Assistant professor at Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville.

Spent writing the book: Six years. The oldest poem in the collection, “The Ayes Have It,” after Trayvon Martin, is from 2012. In some ways, the book started after that tragic tipping point, which intertwines with my origin story in the South.

Time spent finding a home for it: About a year.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: If They Come for Us (One World) by Fatimah Asghar, Citizen Illegal (Haymarket Books) by José Olivarez, Refuse (University of Pittsburgh Press) by Julian Randall, Indecency (Coffee House Press) by Justin Phillip Reed, Virgin (Milkweed Editions) by Analicia Sotelo, A Cruelty Special to Our Species (Ecco) by Emily Jungmin Yoon, Perennial (Coffee House Press) by Kelly Forsythe, and Ceremonial (Orison Books) by Carly Joy Miller.

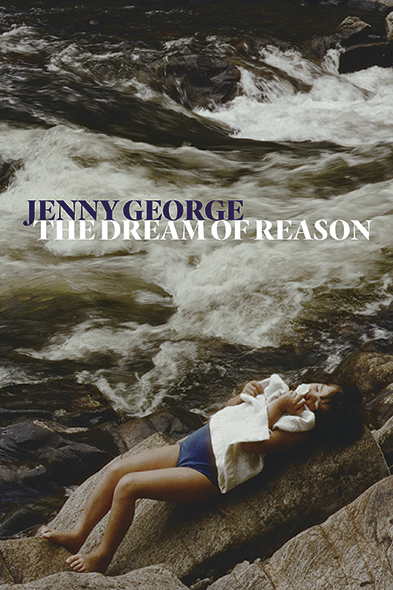

Jenny George

The Dream of Reason

Copper Canyon Press

This is the afterlife, but

I’m not dead. I’m just

here in this field.

—from “Death of a Child”

How it began: The inquiry in these poems is shaped by the question: How much of our aliveness can we bear? Another way of asking that is: How much of our own capacity for violence must we tolerate in order to be fully awake? At the same time, I was very interested in humans’ complex, emotionally charged dependence on animal life and in the relationship between animal consciousness, dream consciousness, and childhood. These threads met in my work.

Inspiration: Fields and rivers; pigs and cows; object relations theory; Texas Hill Country; silence and solitude; Carl Jung; farming manuals; mystic traditions; conversations with my sister; dreams.

Influences: I grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts, the town where Emily Dickinson lived her whole life. Dickinson’s language was some of the first poetry I heard; that musicality and compression is still very much in me. I love Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich for political work with beauty and formal rigor. And Brigit Pegeen Kelly for restraint and mythic intelligence. I also read a lot of psychoanalysis. I read it like it’s poetry, in other words: to be moved, arrested, brought into relationship with my own interior.

Writer’s block remedy: I remind myself that language isn’t my job. Writing a poem isn’t my job. My job is the human job of waiting and listening, and language is just what poets use—like wind chimes—to catch the sound of the larger, more essential thing. Wind chimes themselves are not the point. The point is the wind.

Advice: All the best advice I’ve been given is some form of the same advice: A writing life is a long process, and engagement with the work itself is the antidote to fear and to anxiety around your career. The practice is to move without attachment in a purposeful direction toward what it is you don’t know.

Finding time to write: I have a quiet and minimal life, and I work part-time, so I have space for writing.

Putting the book together: I shuffled my poems around fruitlessly for a long time before I realized there was content missing, which was why the book wouldn’t cohere. But I didn’t know what that content was. My mentor Louise Glück gave me some very good advice: She suggested that I discover the missing material by pushing myself to use new syntax, by writing different kinds of sentences than I typically do. Over time, the new sentences led to the new material that fleshed out the book. Then I sat down and tried various orders for the poems. At some point, the poems just clicked into place, down to the final poem—suddenly there was a deep, precise feeling, like a voice saying “Done.” That was an immensely satisfying moment.

What’s next: I am working on being more courageous. I’m starting to write poems again after a period of several years when I wasn’t writing at all because I was caring for my life partner who was sick with cancer. She died last year. Now I find myself asking: What is really crucial for me to write? What is my artistic responsibility—to my own lived experience, but also to the grave, raw need of the world in these times? Who must I be now as a writer?

Age: 40.

Residence: Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Job: I work in social-justice philanthropy.

Time spent writing the book: Eight years.

Time spent finding a home for it: One year.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Eye Level (Graywolf Press) by Jenny Xie, The Lumberjack’s Dove (Ecco) by GennaRose Nethercott, Ghost Of (Omnidawn Publishing) by Diana Khoi Nguyen, Refuse (University of Pittsburgh Press) by Julian Randall, and Half-Hazard (Graywolf Press) by Kristen Tracy.