What compels someone to write poetry in the first place—to commit to this nuanced, imaginative, and far-reaching art form? One of the ten authors in our twenty-first annual look at debut poets, John Liles, remarks, “I never understood what it is that so many others seem to know. What makes this life worth it, given everything we, a brief iterant species, have done to others, ourselves, across a planet.” In his search “to know” he found a belief in language, how it can connect us. Another poet, Bernardo Wade, writes about where it all started for him: “When I began writing poems, they were mostly nonsensical scribbles I did in the corner of the seafood joint where I waited tables.” No matter their various origins, the poets in the following pages proceeded to create debut books wherein the delicate ecosystem of the poem is carefully tended to.

Clockwise from top left: Gbenga Adesina, Annie Wenstrup, Chaun Ballard, Esther Lin, Nadia Alexis, John Liles, Kalehua Kim, Lena Moses-Schmitt, Daniel Ruiz, and Bernardo Wade (Credit: Eugene Smith)

Daniel Ruiz presents us with poetry that is defined by a surreal, straightforward, and mischievous philosophy (Reality Checkmate). Lena Moses-Schmitt gives us a poetics of perception, of ruminations and hard-earned insight (True Mistakes). Esther Lin, with such coolheaded, certain language, looks unblinkingly at the life of her parents and herself as a previously undocumented individual (Cold Thief Place). Nadia Alexis shows us the power of witness, survival, and reclamation, in her collection of poetry and photography (Beyond the Watershed). Annie Wenstrup recontextualizes storytelling to find a form that works with the intricacies of her speaker’s needs and being (The Museum of Unnatural Histories). Gbenga Adesina sings us a tender hymn equal parts water and elegy (Death Does Not End at the Sea), and Kalehua Kim’s language becomes a matriarchal chant of longing and living (Mele). Wade offers us mercy in the form of poems that maintain a distinct Southern swagger while moving away from bravado and toward forgiveness (A Love Tap). Liles quietly gathers humans and our more-than-human counterparts, attuning to small and big creatures alike (Bees, and After). And Chaun Ballard presents us with a physical book wide enough to hold the extended titles of his poems, which are both breathless and textured, entirely innovative (Second Nature).

In their responses to our questions, these poets candidly and generously share the details of their creative journeys so far. Some of these collections took decades to write and were overhauled completely before landing with their respective presses. These poets remind us to be patient with our growth and to honor the time it may take for our creative vision to align with our skill set, should we hit a literary impasse. Other recommendations to combat writer’s block include deleting social media apps and getting out of your mind and into your body. Alexis tells us to “befriend self-compassion. Revisit your love of writing and make a home there. … Trust that your day will come, and it will be glorious.” Glorious, indeed. These ten poets not only share real-life stories and advice, but also offer us, with their debut collections, new ways of seeing and understanding our outer and inner worlds.

Gbenga Adesina | Annie Wenstrup

Chaun Ballard | Esther Lin

Nadia Alexis | Bernardo Wade

Daniel Ruiz | Lena Moses-Schmitt

Kalehua Kim | John Liles

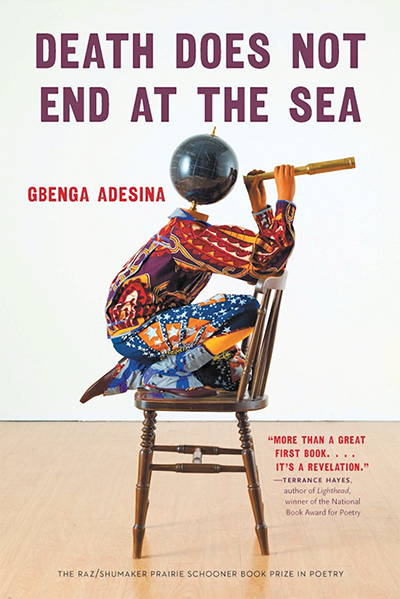

Gbenga Adesina

Death Does Not End at the Sea

University of Nebraska Press

(Raz/Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry)

Look. You must look. You cannot

look away. Their bodies, their torsos, their mouths curve darkly

and arrow down into the water. What do you call a body

of water made of death and silence?

—from “Death Does Not End at the Sea: A Sequence”

How it began: I was haunted by two kinds of journeys. Two life-shifting departures. One was my father’s abrupt death. Every death is a story. It’s that story that haunts. Then, shortly after, I left Nigeria for the United States and began to tick the “immigrant” box, and I wanted to make sense of that in the context of the long and ongoing history of transatlantic journeys, passages, and ruptures. How does grief mutate when it travels across borders? How do you grieve what you left behind? Is fatherlessness the spiritual cousin of nationlessness? There is a line in the long sequence of the title poem that maybe captures it: “We are at the edge / or middle of nowhere, a geography of melancholy, where / no hand of father or nation reach out / to claim us.”

Inspiration: Compulsively rereading Blind Spot (Random House, 2017) by Teju Cole. Samuel Ajayi Crowther’s Yoruba translation of the Scriptures. Reading through years of old notes and journals. Listening to the world weariness in James Baldwin’s voice as he sings “Precious Lord.” Lokua Kanza’s songs. Abderrahmane Sissako’s visually stunning sonnet of a film, Timbuktu. Revisiting old family photographs, especially my parents’ wedding photographs. The pecha kuchas of Terrance Hayes. Reminiscing on the phone with my mother and siblings. Nora Chipaumire’s and Lacina Coulibaly’s dances at Harlem Stage. Passages and their brutal histories. Etcetera.

Influences: Wole Soyinka. I grew up reading his plays and I think some of my ideas about structure come from those works. Aracelis Girmay, Lokua Kanza, and Cesária Évora taught me that a voice can be full of oceans.

Writer’s block remedy: What one might call an impasse or burnout, I would call estrangement, and this estrangement, in my experience, seldom originates on the page. It’s often an estrangement with a root in your spirit. Sometimes it has to do with the multiple masks you are juggling; you are conflicted about who you are and who you think you should be on the page. It’s usually something about spiritual and emotional honesty.

Sometimes it’s an estrangement with a root in your body. You are exhausted. You’re trying to make your body do what your soul has given up on. You need to rest. But sometimes this impasse or estrangement—and this is not a bad one—is because there is a gap between your creative vision and your skills. So, you want to become an apprentice again. In that phase I’m making myself reading lists; I’m waking up earlier or going to bed later; I’m looking for that extra time to see what new muscle or tongue might grow if I dig. What I want to do needs a larger version of me.

And finally, in my experience, sometimes this estrangement has to do with being a poet (or any kind of artist), but operating outside of a poet’s universe of time. Poets don’t do billable hours. Time for us is not linear. The idea of a tangible measure of productivity on a day-to-day basis is sketchy at best. We do our work in a kind of strange clockwork of seasons that is full of circularity and surprises, long stillness and sudden motion. It’s a kind of time that requires a grammar of surrender. But sometimes we are showing up to the page with impatience, with an invisible clock ticking inside of us, with a desperation for completion. We are not thinking of it as language work but as “projects.” We are forcing it. At such times I try to rediscover the discipline of visionary aimlessness. The urgency of witnessing is important, yes, but so is the urgency of play. To get up in the morning and rush to the desk not for any project, but to see what you can do with a cluster of sentences, how far you can extend an image. Language that is less about meaning-making, and more about syntax, rhythm, and spell. You want to give yourself to a kind of work in which the reward originates and is spent within the universe of the work. I find myself teaching with heart, editing other people’s work, translating and marveling at the gaps, bridges, tunnels, and trapdoors between languages. You try to serve language in a way that does not serve any project.

Advice: You must write from a knowing that your life is made of futures. You are going to grow. You can’t tell all the stories in one book. There are books you can’t write now because they are ahead of you. Then write the current book as if it’s the only one you’ll get to write.

Finding time to write: Haha. That’s the hard part. I don’t have a routine. But once there is urgency, I’m trying to write every moment I have.

Putting the book together: I wanted the musical flow and sinusoidal feel my favorite albums have. I wanted the whole thing to feel like a long, brokenhearted prayer—but a long, brokenhearted prayer interrupted by laughter. More practically, I drew an ecosystem of affections and web of my relationships in the book and swung between them. I love alternations. I always have the image of an accordion in my head, expanding and contracting to create music. I tried to do the same with poem length, mood, tone, scale (of history, time, and space), etcetera. I love multiple beginnings and endings within the manuscript bracketed by the fixed beginning and ending at the outer edge—but the seams must not show, it must be subtle—or false endings, where it seems the book can end here and then it revs up again. I kept telling myself this is a dance, a song, and a story. It must have a trajectory and a flow, even a plot—not in a narrative sense, but in terms of emotional motility. To have started the book in one emotional state and arrive, transformed, at another state by the end. I had the order in my head for some time, which was kind of fun but also nearly drove me mad, so I did what I read everyone does, I printed out the poems and spread them on the floor. It helped greatly.

What’s next: A collection of poems.

Age: 36.

Residence: Harrisonburg, Virginia.

Job: I teach poetry and work at the Furious Flower Poetry Center at James Madison University.

Time spent writing the book: About eight to nine years. “Vanishing,” the oldest poem in the book, was written in 2016 and the most recent one was written in 2024. There was some tweaking in early 2025.

Time spent finding a home for it: Four to five years.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: Chaotic Good (Wesleyan University Press) by Isabelle Baafi, FREELAND (Alice James Books) by Leigh Sugar, and A Love Tap (Lookout Books) by Bernardo Wade.

Death Does Not End at the Sea by Gbenga Adesina

![]()

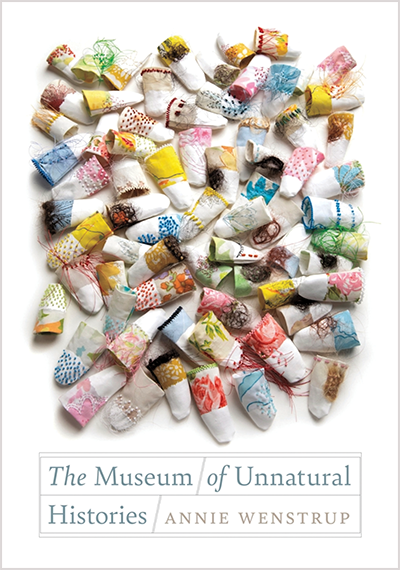

Annie Wenstrup

The Museum of Unnatural Histories

Wesleyan University Press

This is what I learned of the future:

a red salmon, her scale-blushed belly,

her silvered cheeks above her gills.

Her gills like a door in a lift-the-flap book.

Here, hook the crook of your index

finger and pull. There’s the lure.

—from “As Diviner”

How it began: The project was prompted by a desire to understand my experiences of objectification and dislocation. I wished for a way to make sense of my relationships to place, cultural identity, and my body. Instead of providing answers, charting those ruptures led to questions about agency and the gaze: How is being seen different from being stared at? What’s the difference between an object and art? How would I envision an alternate self?

Each individual poem felt like a proxy for the/my body, and the poem’s form reflected a question that I could not answer. I wanted a tangible way to experience the imagined space that those questions inhabited. The book’s conceit fulfilled that desire. It also encouraged me to test if a structure of linked forms could contain an answer to the poems’ questions. I don’t know the test results yet, but the structure did help me work to find the question at the museum’s axis: How did I get here and how do I leave?

Inspiration: For form: DK Children’s books, especially Eye Wonder: Space (2016), and Richard Scarry’s Busytown books. For content: My favorite sections of the book are poems I imagined as responses to something I’d read or heard. Tema Okun’s scholarship, Joyelle McSweeney’s The Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults (University of Michigan Press, 2014), and Daniel Heath Justice’s Why Indigenous Literatures Matter (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018) were generative spaces for the work.

Being part of the inaugural Indigenous Nations Poets Fellowship cohort was a source of inspiration. Our group visited the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian [in Washington, D.C.], and that experience influenced the book’s themes. I don’t think the manuscript would have taken the shape it did without my having seen the Americans exhibit there while also having the benefit of other Indigenous writers processing that experience with me. Hearing the fellows’ and mentors’ critiques of a space that was ostensibly about us reassured me. I felt like there would be other writers who were interested in my questions about the intersections of Indigeneity and whiteness. Equally important, I felt as though I was part of a community that would help me develop a poetics that didn’t replicate objectification. That kind of safety was the precursor to inspiration—it was what allowed me to experience inspiration.

Influences: Emery Blagdon’s [mixed media artwork] The Healing Machine. He made the unseen forces of the world tangible and invited people to move through them and be changed.

Marilyn Nelson’s “Ruellia Noctiflora” from Carver: A Life in Poems (Wordsong, 2001). Nelson’s ars poetica offers a process of re-visioning the world through relationship and wonder. Her work sets a standard for what my poems aim to do.

Sharon Massey’s [copper artwork] Touch (in the time of corona) models how art can be a source of comfort and a source of commentary. It reminds me that touch is the first way of sense-making, and to honor what can be felt and embodied without language.

Tanya Lukin Linklater’s Slow Scrape (Centre for Expanded Poetics & Anteism, 2020) and her multimodal art practice. Lukin Linklater’s book is a smart exploration of how place, identities, and practices are intertwined. I love how her work is concerned with how bodies move through time and locale. I’ve learned so much from how she documents the relationship between environment and body. The event score in the book is modeled after her poem “An Event Score for Kodiak Alutiit 2 (To Aleš Hrdlička)” and the book’s structure is informed by listening to and reading Lukin Linklater’s thoughts on structure in art.

Writer’s block remedy: Peer pressure. The polite term is “accountability partners,” but really, if all my friends are writing, I’ll write too.

Advice: Your first responsibility is to language.

Finding time to write: I schedule my writing and reading time. Once a week I meet with a friend and we work on generative exercises. I read for fun every day, and one to two days a week I read to pursue a question about form, craft, or theory. Reading usually leads to writing, and focusing on how much I’m reading helps me not psych myself out about how much I’m (not) writing.

Putting the book together: As a reader I want to experience text like I did as a kid. The oversized pages, images, and playfulness enthralled me. I wanted my manuscript to have that same immersive feeling.

I also thought about something Dawn Biddison, the museum specialist for the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center in Alaska, told me. She said the value of an object was in its ability to foster meaningful encounters between the viewer and the world. That idea challenged my theory about museum objects as zombies—without life but trapped in the world—and I wanted to explore those two ideas in the text. I tried to place both concepts in proximity to each other in the book.

The outlines of the museum’s structure came together easily, but I labored over the last 25 percent of the manuscript’s order. I’d framed the problem as needing to move the curator out of the museum without letting the visitor leave. I couldn’t let go of that problem until Suzanna [Tamminen], my editor [at Wesleyan University Press], sent me the marketing copy she’d written for the book. It posited the museum as a space that was entwined with the real world. I’m thankful that her reading allowed a re-visioning of what the museum’s structure could be.

What’s next: I’m excited about a project I’m working on with Mary Leauna Christensen and Noʻu Revilla. Together we’re coediting an anthology of Indigenous poetry and craft essays for Wesleyan University Press. I’m also working on new poems and essays—it’s a little daunting to be at the beginning of a project without knowing its outline yet.

Age: 39.

Residence: I live on the lands of the Dena people of the lower Tanana River in Fairbanks, Alaska.

Job: Writing.

Time spent writing the book: I wrote the first draft of my manuscript in two years, it was part of my MFA thesis. After I graduated, my mentor Katherine Larson gave me the best feedback possible: My thesis was not ready to be my first book. Initially it was hard to hear. I felt very dramatic about the whole thing. However, it was also flattering to learn that she thought the project had more potential than I could see. It took another two years of working on the manuscript before I was ready to send the final draft to my publisher.

Time spent finding a home for it: In early 2023 I submitted to a handful of publishers and contests and received rejections. It was so discouraging; I’d spent a year revising the manuscript and really thought it was ready. Then that summer a conversation with the poet Asa Drake changed my perception of what I wanted the manuscript to achieve, and I understood that I would need to complete another revision before I was ready to begin a new round of submissions. While I was working on that revision, Suzanna read one of my poems that had been published in a journal and solicited my manuscript. I feel very lucky, both that the manuscript was solicited and that Suzanna was open to working through the revisions I wanted to pursue but didn’t yet have the skills to complete.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: Forgive the Animal (Cornerstone Press) by Sarah Pape—technically this was released in 2024, but it’s been close to my side all year. I’m drawn in by the book’s formal elements—its careful structure and its language. I’m also moved by Pape’s commitment to tending and attending, how she insists on documenting rupture and repair:

“repairing. Some integral part of him yearned to fix things, to

help, even when the other hand was destroying in darkness.”

Mele (Trio House Press) by Kalehua Kim:

“out of the womb was reason enough to keep trying.”

night myths • • before the body (Red Hen Press) by Abi Pollokoff:

“hungered. against the

birchhymned absence shorn of

breath & bismuth.”

Blue Corn Tongue: Poems in the Mouth of the Desert (University of Arizona Press) by Amber McCrary:

“All my life I tried to forget who I am

and live like a bright clean canvas

unstoried but well kept”

Birds at Night (Texas Tech University Press) by Ibe Liebenberg:

“you. You, reduced to participating transient,

as they continue to remember

you all wrong. Not as a flower on a hillside, wanting”

The Museum of Unnatural Histories by Annie Wenstrup