I don’t know that there’s been a time in my life when there was not a genocide happening,” Donika Kelly tells me, her deep voice, redolent of her youth in Arkansas, flattened by grief. Or, no, not grief. Despondency.

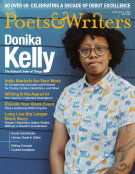

Donika Kelly, author of The Natural Order of Things. (Credit: Michelle Kay Photography)

We’re speaking over Zoom about her third and latest poetry collection to come out from Graywolf Press, The Natural Order of Things, published in October. As in many conversations among writers during these dark days, we have shifted from craft to the perplexing question of what, in the face of the world’s ongoing and advancing horrors, is the point of writing in general, and writing poetry in particular. Though celebrated for her previous collections—her debut, Bestiary (Graywolf, 2016), received the 2015 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, among other distinctions, and her sophomore collection, The Renunciations (Graywolf, 2021), was a finalist for the 2021 National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry—Kelly is not immune from such existential questions. If anything, as a talented poet with a preternatural sensitivity to the world, her place in it, and her emotions, and as a political and community-oriented thinker committed to justice, she is more apt than most to wrestle with the ethical conundrum of making art at a time of collapse and dystopia. “The move forward into fascism that we’re experiencing right now?” she tells me. “It’s like they said, let’s take the hoods off. Let’s just do this thing. It’s hard to make sense of the kind of work that my book could do or is doing in the face of that.”

She pauses for a moment, bright eyes focused on something in the near distance only she can see. “I know I like the book and these poems, but why now?”

This is a question that the collection itself answers. In a time when escapist fantasies dominate the fiction charts, The Natural Order of Things is not a book written outside of the world but one that engages with it and that dares to ask: Trauma has happened and is happening before our eyes, and healing might not be a place but a never-ending, nonlinear journey, so, then, why laugh? Why make art? Why make love? With this collection Kelly says to the reader, Come close, listen, let me tell you why, and let me tell you too why we fight, why we write, why and how we have survived and will keep surviving.

The answer? In a word: joy.

![]()

The first thing one notices about The Natural Order of Things is that it’s a slim volume. “I decide on a page limit before I start,” Kelly says. “I like a short book with a structure that feels somewhat apparent, intentional, meaningful. That feels like a poem.” In this case she set a sixty-page goal for herself at the outset and came in a few pages shy, with a collection that isn’t too tight but has a holistic quality to it. There are no distinct sections—Kelly thought that would imply a discreteness she didn’t want—but the book has a clear sense of movement from poems about family and land to ones about new love and sex, to art and politics, to community and, again, to love, but in a different register than before, a love rooted in home and self.

Delight guided Kelly in this organization. She relishes when images recur in collections, when a later poem sends her riffling back to find the earlier poem or poems in which that image or phrase appeared. “These moments are associative; there’s a relationship between them,” she says. “There’s pleasure in that. Not narrative pleasure, just vibes.” As the title implies, images of nature are consistent throughout the collection, along with an exquisite and rhythmic use of language born in part of the poetic but also conjuring the music of embodied speech, the cadence of the shorthand shared among family, friends, and lovers. These are poems you’ll want to read aloud.

Much of that language, particularly in the book’s first movement, has its origins in Arkansas, where Kelly’s family is from. She spent the first thirteen years of her life in Los Angeles, Compton to be specific, which during the nineties was a site of frequent gang violence as well as the 1992 civilian uprising and militarized response by police, National Guard, and federal troops after the acquittal of the LAPD officers who brutally beat Rodney King. Kelly experienced and witnessed all of this. Shortly thereafter her parents, both from the South, moved the family to Arkansas, a place Kelly describes as peaceful, green, and “very sticky, incredibly sticky, in terms of language.” Because she had been around Southern accents all her life, this new environment felt very familiar to her ears. “I love the sounds down there. The variations inside that accent are really beautiful. And the things that people say? The figurative language? It’s so rich.”

Kelly moved to Iowa City about five years ago to teach in the English department at the University of Iowa. The dry, undramatic accent of the Midwest had her longing for the slow, thick drip of Southern speech, so creatively she leaned into the soundscape of her youth, bringing her family forward as characters and voices within her poems. In “Its gone be what it is,” Kelly directly quotes her sister, “you got me bent, / buddy.”—a line her sister said in conversation when describing a relationship with a troublesome man. “The way she said it,” Kelly tells me, shaking her head in awe, “I’ve never written anything as good or evocative as that. I told her later, after we had done the emotional work, ‘I’m gonna steal that.’”

“Its gone be what it is” includes numerous family quotes and references, including one of the most delightful recurring figures in the collection, Juel Lee, the poet’s great-grandmother. Born in 1919, Lee was old by the time Kelly met her at the age of seven. During a summer between college semesters at Southern Arkansas University, when Kelly wasn’t on speaking terms with her parents and needed a place to live, Lee took her in, something people believed Kelly was doing as a favor for elderly Lee, when in fact it was a blessing Lee gave to the young poet. “We spent a lot of time together,” Kelly says, “just sitting outside on the porch, being hot, not doing anything. She was really funny, super sharp, and so cute. I miss her.” Lee didn’t ask Kelly to pay bills or do anything other than just be there to run errands, cook together, and share space. In “Tell It Short,” Kelly writes of this time:

… I was little and lost

the season I learned to be still, to pass

a piece of time with remembering—a comfort

to remember now, to make present, for a little while,

to bring her, as from a great distance, closer.

To some extent, putting these recollections on the page was a surprise to Kelly and will be as well to readers familiar with her work. Pieces in her earlier book The Renunciations directly address the trauma of Kelly’s sexual assault at the hands of her father. To this day, maintaining good boundaries with her immediate family is a necessity. But her extended family? People like her great-grandmother, as well as her aunt, her sister, and her niblings, have been generous to her. The Natural Order of Things celebrates that spirit of sharing, of storytelling, and of languaging. Her voice ringing with gratitude and a touch of pride, Kelly tells me, “Whatever I’m doing as a poet is a natural extension of my family.”

![]()

Two poems serve as tonal bookends to The Natural Order of Things. The first, “Brood,” evokes the darkness of The Renunciations, as the speaker churns with memory “For slow months at rest in the hole / I’d made in myself / A frozen ground.” And yet a thaw is on the way. By the book’s end, that darkness has transformed and transferred into lighter material. Though the final poem is titled “Suicide Watch: Spring,” the piece is a celebration of life. This capstone sings the themes of the entire book in miniature, from memory (“So much has happened / that I would never have known / I could remember”) to land (“the hills scraped with rust before white / before petal before green”) to love (“loving you in the dark—some small / animal in the grand scheme”). It ends with a simple acknowledgement: “I’m happy, sometimes, to be alive. / That such happiness could have happened at all.” This happiness, though tempered by that “sometimes,” is powerful, radical, for a Black, queer poet, a survivor of family trauma with one foot in the violence of inner-city Los Angeles and the other in the historical tensions of the South, to declare.

“When Kelly first sent me the early manuscript of The Natural Order of Things, she said on the phone, ‘I think I wrote a happy book?’” Jeff Shotts, Kelly’s editor at Graywolf, tells me. “The question her voice made of that statement says a lot—that happiness is uncertain, that at times we can’t easily recognize it, that it is often hard-won.”

That happiness is political as well, particularly in this time of openly white-supremacist oligarchy. In the poem “Major Arcana,” Kelly name-checks the poet and intellectual Audre Lorde. When I ask her about Lorde’s idea of joy as an energy for change, as a form of resistance to oppressive power structures, Kelly says, “Audre Lorde is a writer and thinker who has been important in my growth as a person, primarily around being present and creating space to be a complex person who has lots of different kinds of feelings and many ways of knowing.”

![]()

Kelly talks with me from a bright sunroom where trees wave in the breeze in the window behind her, around which grow potted plants of various sizes with vibrant leaves reaching toward the glass. She admits that though she cares for them, they are the verdant wards of her wife, the author Melissa Febos. This is Kelly’s second marriage. Her first led her to believe that partners needed to be together as much as possible and that her desire for solitude was detrimental to the relationship. Febos has helped her understand that, as an artist, solitary time is not only valuable, but also necessary. They explicitly navigate their disparate requirements for solitude—Febos, for instance, enjoys going away on residencies, while Kelly likes to write at home—as well as their need for feedback. “Once I finish drafting something and it feels good enough, I’m like, ‘Are you ready to hear my new poems?’ And Melissa is very much available for that.”

She continues: “Some of that is me just wanting to hear how the poem sounds when I read it aloud, and some of it is wanting to share in the excitement that I made something.” At this early point in the process, Kelly typically wants to hear about what is working in the poem, what sounds interesting, what captures the listener’s attention. “And I like being told I did a good job!” Kelly adds.

“I love how being her early listener has helped me be a good listener overall,” Febos tells me. She appreciated how Kelly made clear, early on in their partnership, what kind of feedback she found most helpful. “This encouraged me to define exactly what I want from readers at specific stages of writing,” Febos says. “It can be so disruptive to get feedback before one is ready and so wise to cultivate the ability to discern whether you need encouragement or critique. I don’t need critique until quite far into the process, but I didn’t always know that.”

Their intellectual and artistic collaboration isn’t only a formal one; it is baked into the foundation of their love. Febos says they talk about poetry, memoir, publishing, various obsessions, teaching, at “any old time: when we are eating or cleaning or driving to work or about to fall asleep. Because of her my domestic life is threaded through with conversations, my own thoughts intercepted and deepened by hers.” The artistic result of this connection, Febos continues, is that their books “are in conversation with each other, which is a mirror of the ways that we are always literally in conversation with one another.”

Kelly makes an appearance at the end of Febos’s most recent memoir, The Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex (Knopf, 2025), about a period of celibacy after decades of consecutive relationships, and Febos appears in numerous poems in The Natural Order of Things, some of which sing of their love and some that celebrate their passion and sex life, such as “Self-Portrait as a Woman Who Kneels over Her Beloved’s Face.” When I ask Febos, long celebrated for her unflinching and visceral writing about sex and pleasure, what it was like to read about herself as an erotic muse in Kelly’s work, she said, “Absolutely delightful. Just desserts. I love seeing her observe herself and me through her craft.”

Kelly echoes this note about observation when she tells me that one of the most special aspects of their literary romance is how they view each other’s entire body of work in ways that, individually, they themselves are unable to do. For instance, even though Febos’s celebrated essay collection Girlhood (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021) covers a period of her life after The Dry Season, Kelly was the one who recognized that she needed to write the former book in order to pen this later one. Similarly, she says, “I had to write my other two books before I could write a book that, I think, feels as warm as this one. I needed to move through some pretty big experiences, do some processing both outside of the work and in the work, to figure out what it is that I wanted to do. The poems in The Natural Order of Things feel like I’m actually moving in the direction that I’ve been saying I wanted to go for some time.”

![]()

The new book came together similarly to Kelly’s first book, Bestiary, in that it began as a big stack of poems. However, with Bestiary, Kelly was in what she calls a “less connected” place in her life, “working toward becoming more integrated, present, and self-aware.” Writing the poems in Bestiary helped her with that, and yet it was a process that was ongoing through the book’s composition, which meant that the book often changed shape while Kelly sent out various drafts of the book for years. These days she feels more confident and approaches this book as an artifact, carefully considering its form and how it moves.

The oldest poems in the collection were composed at the same time she was writing The Renunciations, while the most recent were started in 2023. Early that year Kelly printed out poems she had accumulated and began organizing them, looking for pieces that spoke to one another and grouping them into what would become the movements of the book while setting others aside for use in later projects. By September she had a draft she deemed solid, but she preceded to sit with it, letting it percolate, wanting to be sure, before sending it to Graywolf in December. The book was accepted in early 2024, at which point she began working in earnest with Jeff Shotts, who has edited each of her collections.

“Jeff is patient with me because I’m very specific, and I don’t like line-edits,” Kelly tells me. “He’s had to figure out how to help me understand the poem in a different way, with queries that lead to a line-edit or inform a line-edit.” With a laugh she admits there have been times that she’s had absurd, outsize reactions to his ideas. With The Renunciations, for instance, he suggested Kelly include section breaks “an outrageous number of times” before she finally considered it and came around to the idea. When she did, he suggested she number the sections and says she replied that the idea made her want to vomit. “Finally, I thought, this man has not asked me to do very much in my books, and he keeps asking me to do this one thing. Why might that be?” Shotts doesn’t rush Kelly on the production of a book, which means they’re able, over time, to think carefully and get to a place where they agree the collection is where it needs to be.

For his part, Shotts says, “I love the moments when Donika pushes back or tells me she needs to ignore certain edits and suggestions because, even if I look a little foolish in that moment, it means she is rightly defining and protecting her poetic voice. I live for that kind of confidence that draws necessary lines to say, ‘Thank you, but I have to sound like this.’”

“I’m the only one who can figure out my work,” Kelly affirms. But Shotts is instrumental in collaborating with her. “In this book,” the editor says, “we discussed how to justly convey the feeling of finding one’s way and the shock of realizing one’s natural place in the world, especially when that has previously felt impossible or out of reach. It meant for me, as editor, to listen to Donika and to the poems and to strive to enhance what the poetry is already working toward.”

![]()

Everyone who speaks about this collection, including Kelly herself, notices a through-line but also a stark difference between The Natural Order of Things and Kelly’s previous work, a move into new, necessary territory for the poet. Shotts says, “Donika’s first book, Bestiary, sets the conditions for the reader to glimpse and track the profound trauma that is then confronted and survived in The Renunciations, after which The Natural Order of Things becomes a reimagining of possibilities, a recalibration of life’s trajectory, after the one who survived comes to understand that she has survived.”

The poet and filmmaker Ladan Osman, a friend from Kelly’s grad school days at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas in Austin and an early reader of the collection, says that if the first two books revealed Kelly’s seed bank of ideas, “The Natural Order of Things is the seed bank in bloom. The portraits, voices, and scenes in these poems are so carefully faceted, their brilliance is piercing and undeniable.”

Today we are surrounded by the oppressive mechanisms of destruction, degradation, injustice, and corruption by the most wealthy and powerful in our global society, and at times our implication in this, and our powerlessness, overwhelms. As Kelly writes in “I never figured out how to get free,” referencing the catastrophes we witness online daily:

The war was all over my hands.

I held the war, and I watched them

die in high definition.

Many of us feel daily traumatized and despondent. And yet to not love, to not make art and appreciate it, to not spend time with family and friends who enhance and support us, to not remember the past and dream of the future, to not see the world and marvel, to not love, would be to give in, to give up, to bow down. Evie Shockley, a poet and fellow member of the collective Poets at the End of the World, a group of five Black women poets and activists, nods at this when she says, “The Natural Order of Things is trained more on beauty than on pain.”

As Kelly puts it, “I have a high capacity for sensitivity to the sublime.” She sees joy in the ridiculousness of poets who love nothing more than to wax on about the moon or a herd of deer grazing in the woods. What a wonderful thing, she thinks, the way poets as a community observe the world, the way they attune to pleasure, the way we all can, if we choose to. As Osman puts it, “This book is right on time because one antidote to despair is presence.”

Earlier this year, on a glacier cruise off the coast of Alaska, Kelly witnessed sea otters rafting together in the water, with young on their chests. She was moved by this. “I was like, they’re alive, I’m alive, and part of what comforts me is that we are not at the center. You. Me. Humans. We affect them, imperil them even, but we are not at the center of the sea otters’ lives in a way that’s legible to them. We live on a beautiful planet, interconnected, in proximity to and alongside so many different beings.”

The poems in this collection recognize our individual smallness in the natural order of the world and its history and locate within that tininess a massive and abiding presence, awe, stillness, strength, and joy, a way to survive through the most traumatic of times. What a gift Kelly has given us. Or, no, not a gift. A blessing.

An excerpt from The Natural Order of Things

I found myself careless in the crossing

I grew, a young conifer evergreen in sorrow, yes,

but in summer too: yellow from bark to heart,

bound east or west by rivers red with clay

or blood or both. I was careless with my saplings,

my seeds carried on the wind or in the gut

of some ruminant bound to bank and the water’s

wandering. Silt in the water and the missing too.

My grandparents, on all sides, drawn west,

breaching one river, another, until no river,

bank or crossing, but finally an ocean

of sun they could die in. Each body returning

to the source. The river of my mind

running clean through the estuary of my mind:

my own return, a watershed scaled to loss.

“I found myself careless in the crossing” from The Natural Order of Things by Donika Kelly. Copyright © 2025 by Donika Kelly. Reproduced with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota. graywolfpress.org

Brian Gresko is a writer and illustrator based in Brooklyn, New York, who co-runs Pete’s Reading Series. Gresko is a founding member of Writing Co-Lab, a teaching cooperative.