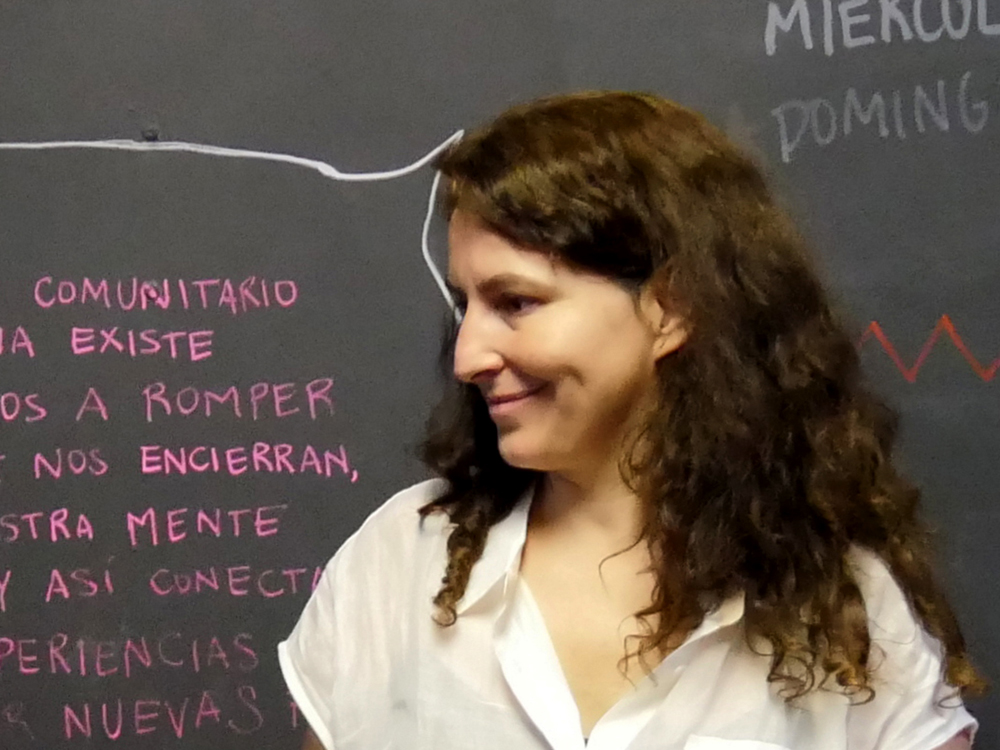

Claudia Prado is an Argentinean poet and documentary filmmaker. She is the author of three poetry collections: El interior de la ballena (Nusud, 2000), which won the third Fondo Nacional de las Artes Poetry Prize in 1999, Aprendemos de los padres (Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, 2002), and Viajar de Noche (Limón, 2007). She has codirected the documentaries Oro Nestas Piedras, about the poet Jorge Leonidas Escudero, and El Jardin Secreto, about Diana Bellessi. Prado is the recipient of grants from the Fondo Nacional de las Artes in Buenos Aires, Argentina and the Queens Council on the Arts in New York, as well as a participant at the NYFA 2018 Immigrant Artist Mentoring Program for Social Practice. She facilitates creative writing workshops in Spanish in New York and New Jersey, some with the support of Poets & Writers.

How did your work with the National Domestic Workers Alliance begin? What drew you there?

How did your work with the National Domestic Workers Alliance begin? What drew you there?

I’ve been running writing workshops for fifteen years. When I lived in Argentina, as part of an organization called Yo no fui, I ran a writing workshop in a women’s prison where I learned that, in very difficult situations, writing can be an especially valuable and meaningful practice. After arriving in this country, I kept organizing workshops independently, always in Spanish. I wanted to offer workshops that would be accessible to the entire Spanish-speaking community, most of all to those who felt an urgency to express themselves and to share their experience but who couldn’t afford to pay for a workshop. I believe that the opportunity to write in our own language and revisit the possibilities and beauty of it makes us feel at home.

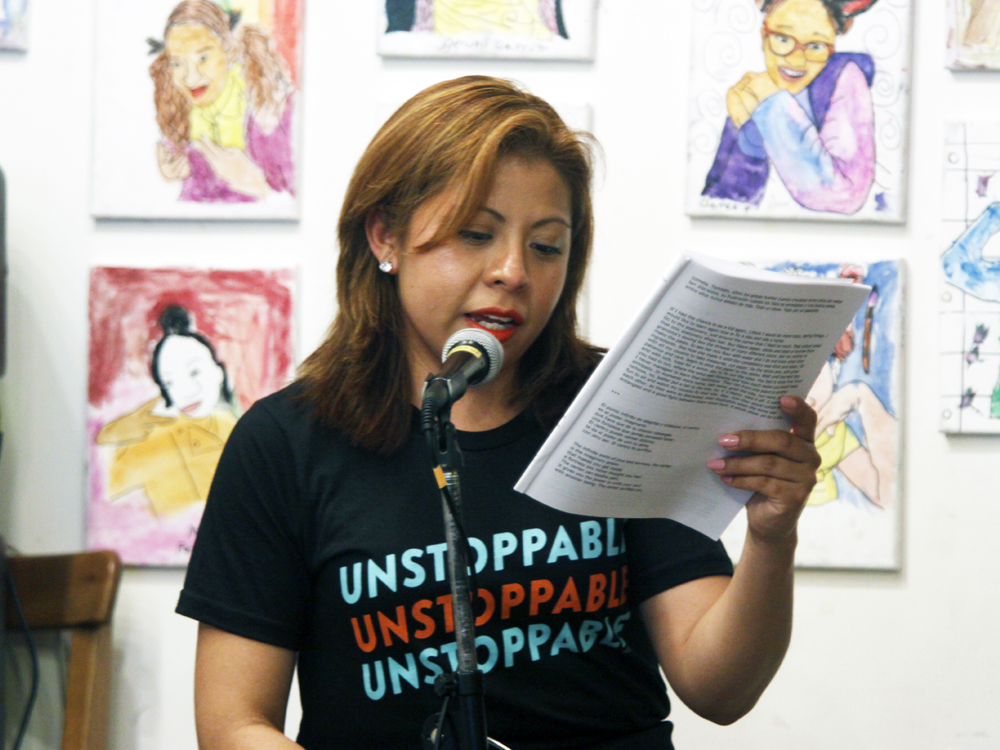

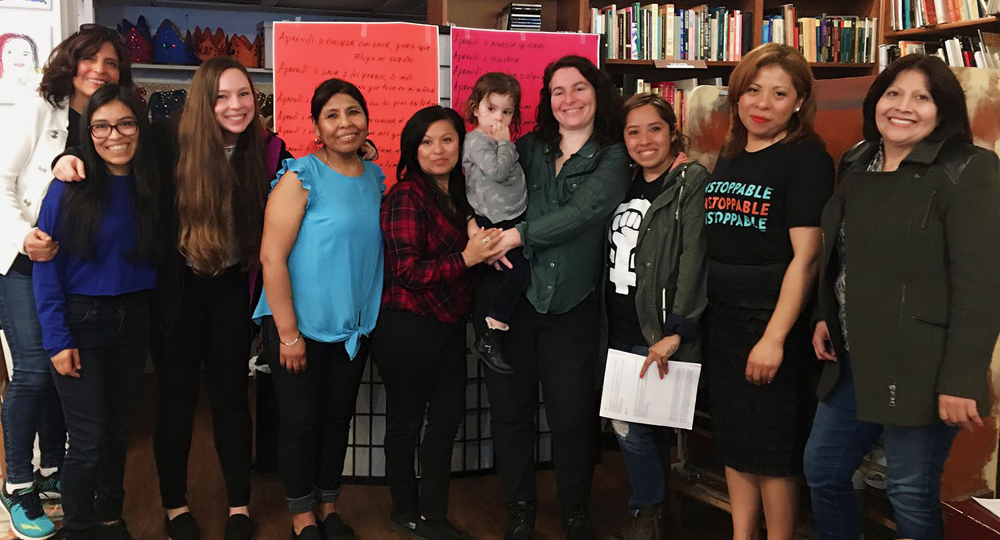

I began organizing free workshops at Word Up Community Bookshop, a beautiful bookshop run by a collective of volunteers. It was through Word Up that I learned about Poets & Writers’ Reading & Workshops program supporting workshops like the one I was running. At the same time, an artist friend of mine, Sol Aramendi, contacted me about the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA). I worked with them for the first time in 2016. It was a very good experience, which we decided to repeat in the years that followed. This year, we’d like to print a bilingual anthology of the writing produced throughout the last three years of the workshop.

Are there any techniques or exercises you use to encourage shy or reluctant writers to open up?

I choose the readings for my workshops very carefully. I try to bring texts that I myself enjoy very much, and that can speak to a wide range of people, including those who aren’t in the habit of reading literature. During the workshop session itself, I dedicate whatever time is needed to the reading and discussion of the texts. For example, if we read a poem, we tend to do so several times. This way of reading tends to bring us to a shared place, separate somehow from everyday life. I also spend time thinking about prompts that invite writing about what is closest to us: what one did that morning, one’s own childhood, one’s language. Often, in the first few sessions, I think of exercises separated into parts: first, simply note your perceptions, memories, possible interlocutors, etc., and second, create a text from those notes.

We talk about how the ability to create with words isn’t something alien to us—something that belongs only to those who had the privilege of studying and spending time reading—but rather something that we all do when we speak to each other in everyday life. We also talk about how writing is generated starting with a draft and then through multiple rewritings, not in one shot and then set in stone. These conversations also help us get writing.

We talk about how the ability to create with words isn’t something alien to us—something that belongs only to those who had the privilege of studying and spending time reading—but rather something that we all do when we speak to each other in everyday life. We also talk about how writing is generated starting with a draft and then through multiple rewritings, not in one shot and then set in stone. These conversations also help us get writing.

In addition to working with NDWA, you’ve recently begun working with the Hour Children/Hour Working Women Reentry Program. How did that collaboration begin? Have there been differences between programs?

Ever since I moved to New York, I’ve thought about the possibility of continuing to work with women who are in prison or have recently been released. This year I was able to do this work thanks to the collaboration with HC/HWWRP and the support of Poets & Writers. The women I worked with were dedicated readers and had writing experience. One particularity of this group was that, even though Spanish was the language they spoke as children and with their families, currently they live their lives primarily in English. As a result, they experienced the workshop as a return to something familiar and very personal, which they had set aside. On the other hand, the moment when a woman is released from prison and is trying to rebuild her life is extremely difficult. These circumstances also made for a different working dynamic and meant that the texts created and shared in this group would be unique to their experiences.

What has been your most rewarding experience as a teacher and as an artist?

One of the happiest moments I have experienced is seeing how a person discovers that she enjoys reading and writing, how she begins to see it as something of her own and to dedicate time to it. Seeing how her expressive possibilities grow and how the texts become a way for her to think about herself and to relate to others—it’s very moving. When the workshop becomes a space that allows for such writing that can only come from a particular reality and a particular experience, we can all feel and see how it is so valuable.

Support for the Readings & Workshops Program in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Frances Abbey Endowment, the Cowles Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Photos: (top) Claudia Prado (Credit: Eduardo Piovano). (middle) NDWA reading (Credit: Neshi Galindo). (bottom) NDWA workshop members (Credit: Adriana Mora).