P&W-funded Jo Scott-Coe is an associate professor of English and creative writing at Riverside City College in Southern California. Her memoir in essays, Teacher at Point Blank (Aunt Lute), was listed as a “Great Read” by Ms. Magazine. In 2009, she won the NCTE Donald Murray Prize for writing about teaching. Her nonfiction and interviews have appeared in many publications, including Salon, the Los Angeles Times, and Narrative. She is currently at work on a collection of lyric meditations about American public performances of violence since the UT Austin shooting in 1966.

We’re all grabby. It’s a healthy part of the self-respecting writer’s condition in a real way. We want our writing to be better. We want readers and good reviews. We want help and friends in high places. We want book sales. We want a thousand “likes” or “favorites” or shares of our latest FB post or Tweet. We want fair contracts. We want editors to value our work. We want bylines, prestigious prizes, and $1.50 per word. We want a room of our own. Of course we do!

But too much grabbiness can often come off as myopic, desperate, and frankly ordinary. Despite all those late nights and early mornings crouched alone at the computer, this writing and publishing deal is, in the end, a highly social activity. How to keep from being just another pair of grasping hands? Here are a few suggestions, based on my own observations and missteps over the past two decades.

When you attend somebody’s reading, plan to buy the book or e-book. If you read alongside someone else, trade books or links or cards—trade anything that creates reciprocity. I don’t care if you “just don’t like his aesthetic.” I’ve attended way too many sad events where everyone has a book or chapbook to sell, and no one buys or exchanges any work. Any! If you can’t afford a book this time, make a plan for when you will. Figure out other ways to circulate literary capital. Then, when you can afford it, buy a book and give it to someone else.

If you’ve been invited to read as a guest, especially if you receive an honorarium, consider donating one or two copies of your book to the organizers to give away or auction off at their discretion.

For every one time you talk about your own project, talk up someone else’s latest thing. Sprinkle that love everywhere. This is easy and fun. I’m thinking right now about two first books by two great poets on my winter reading list: Kevin Ridgeway’s All the Rage, and Jeffrey Graessly’s Cabaret of Remembrance. I’m also looking forward to the upcoming issue of Chaffey Review, a biannual journal that this week won an award for the best multi-genre two-year college literary magazine. Hooray for all of them!

Write “charming notes” on real stationery—or in thoughtfully composed emails—to people whose work you admire, at every level of the achievement spectrum. Don’t calculate an outcome, just move onto the next charming note. In the late 1990s, I sustained a several-month exchange of long letters with my literary crush at the time, but the exchange ended and he let me down easily when I eventually inquired for an interview. The interaction left me feeling both green and clumsy. Later on, during my MFA program at UC Riverside, novelist Susan Straight made sure all of us students read Carolyn See’s book, Making a Literary Life. See elaborates the finer points of the gratuitous charming note, emphasizing brevity, timing, and the lack of a mercenary agenda. I’ve never regretted sending one of those notes. Ever.

Not to get all Downton Abbey about it, but have some grace, for God’s sake. Consider your approach. We all have to compete with strangers for gigs and offer proposals in a changing literary marketplace, and we all need to request favors now and then. It’s understood. Still, don’t Tweet, IM, or DM an offhand request for a blurb to a person you’ve never met. Put some actual thought into the request. (How are you different from the spammer selling weight loss supplements?) Also don’t be the guy or gal who only reaches out to literary friends and allies for a letter of recommendation, free editorial services, or career advice. (See “charming notes” again.)

Subscribe or donate to a literary journal that rejected you. This balances out the ironic expectation you may have that all content should be available for free (everybody else’s content, that is). This subscription thing is easy if you enter one contest a year, because most contest fees include a year’s subscription.

Here’s one that’s practically a cliché: Accept a compliment. This is a big problem for me, not because I receive so many compliments all the time, but because like lots of people, I was not socialized to accept praise very well. At a reading several years ago, a co-performer said something spontaneously generous as she introduced me, and I felt awkward and undeserving. As I took my place at the mic, instead of saying, “How kind of you,” or “Thank you for saying that,” I actually said (cringe, cringe, cringe!), “That is a little horrifying.” Here was this lovely person saying something benevolent and off-the-cuff, and I had rebuffed her effort. There’s no way to take the moment back now, but I can do my darnedest not to repeat the icky performance.

Develop an internal validation system that allows you to share problems without raining on anybody else’s parade. I had a bizarre, frankly violating experience with an editor at highly desirable venue several years ago, and it led to a mutual termination of my acceptance contract. I was disappointed, but I was also actually proud of the resolution and glad to walk away. When I shared this story as a cautionary tale with some other writers, one of them (who had a piece under consideration with the same editor) asked if I was advising them not to submit to this publication. I shook my head. “Heavens no. If it works out for you, that’s fantastic,” I said. “But if something gets weird in the exchange, you don’t need to feel bad about that either.” The writer’s brilliant story did get accepted and published by the editor without incident. My piece was published elsewhere. Win win.

Last but not least, just say “no” already. You’ve agreed to contribute to another blog? And proofread a friend’s manuscript? And teach a ten-week workshop for free? And learn html so you can retool your own website? All while completing your own taxes in January, and schlepping the kiddos to school, writing query letters to agents, and preparing to host the birthday party? Give it a rest already. Give yourself room to be selective, and let your “yes” mean something energizing for everybody.

I offer these imperfect suggestions realizing that not all will apply to everyone, and that every writer could add more ideas to the list. In fact, the more inventive we get with offering modest gestures of sincere enthusiasm and good will, the more tempered all our necessary assertions of self-interest become as we bump into each other around the literary water cooler. There are real advantages to that kind of energy, and the beginning of a new year is a great time to assess this aspect of our writing lives.

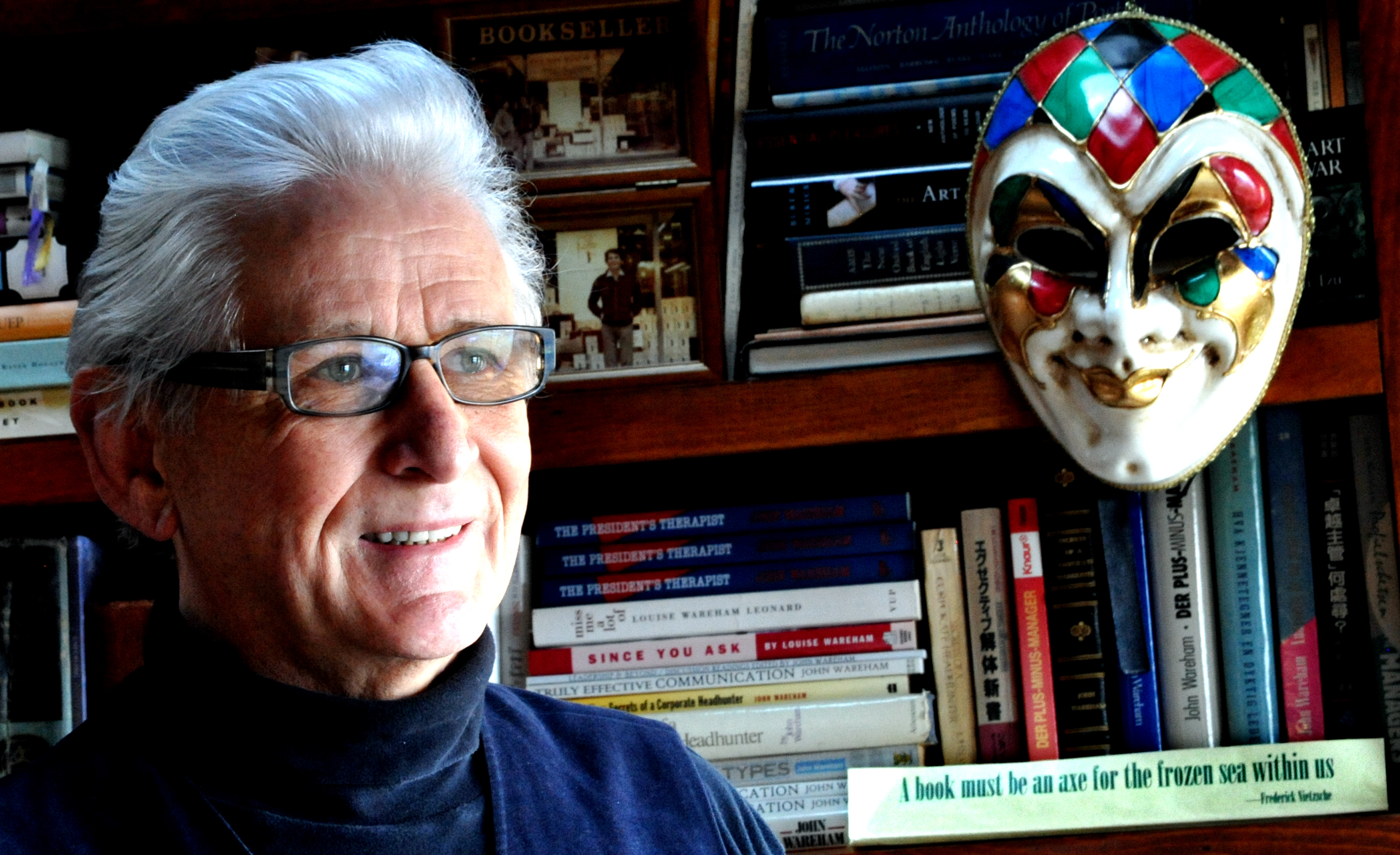

Photo: Jo Scott-Coe. Credit: Wes Kriesel.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

I have spent a lifetime advising corporations how to select and develop winning teams and leaders. One day nearly twenty years ago, an aspiring executive client with a drug habit wound up in Rikers Island, and gravitated to a rehab program.

I have spent a lifetime advising corporations how to select and develop winning teams and leaders. One day nearly twenty years ago, an aspiring executive client with a drug habit wound up in Rikers Island, and gravitated to a rehab program.