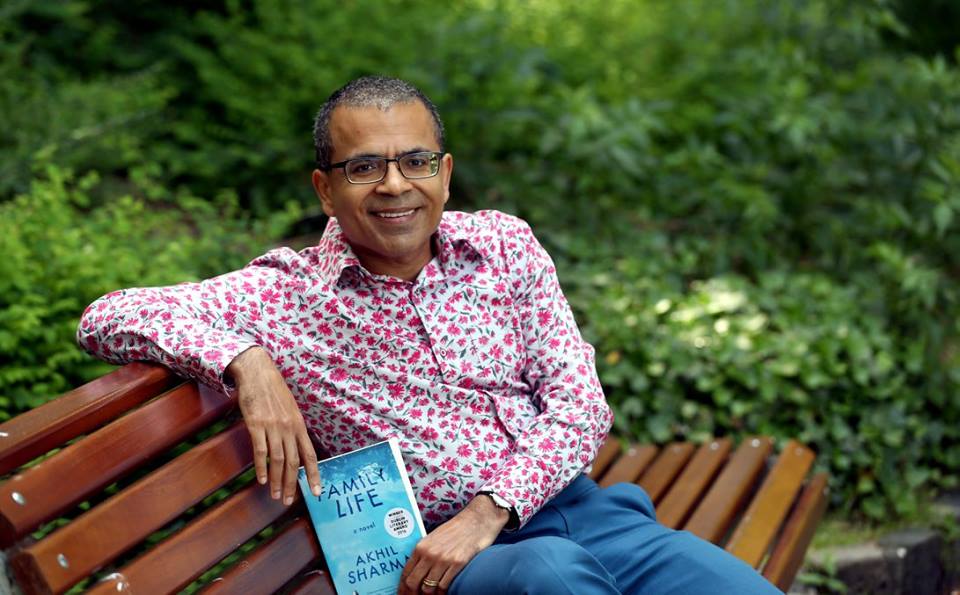

Akhil Sharma Wins 2016 International Dublin Literary Award

The Dublin City Council announced last week that Akhil Sharma has won the 2016 International Dublin Literary Award for his novel Family Life. Sharma will receive €100,000 (approximately $113,000). The annual award, which is one of the world’s largest prizes for a single book, is given for a novel written in or translated into English and published in the previous year.

The 2016 judges were Meaghan Delahunt, Carlo Gébler, Ian Sansom, Iglika Vassileva, Juan Pablo Villalobos, and Eugene R. Sullivan. They selected Family Life (Norton) from 160 titles, which were nominated by libraries in 118 cities in 43 countries. Sharma’s novel, which tells the story of a family that immigrates to America from Delhi in 1978, was nominated by both the New Delhi–based India International Centre Library and the Jacksonville Public Library in Florida.

“Suffering and the struggle to ameliorate suffering are not unknown in fiction but Family Life pulls off the extraordinary feat of showing them in their correct alignment,” wrote the judges in their citation. “Closing the book, having known this mix of light and dark, you are left with the sense that while reading you were actually at the core of human experience and what it is to be alive. This is the highest form of achievement in literature. Few manage it. This novel does. Triumphantly. Luminously. Movingly.”

The 2016 shortlist included Outlaws by Javier Cercas, translated from the Spanish by Anne McLean; Academy Street by Mary Costello; Your Fathers, Where Are They? And the Prophets, Do They Live Forever? by Dave Eggers; The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky; A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James; Diary of the Fall by Michel Laub, translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa; Our Lady of the Nile by Scholastique Mukasonga, translated from the French by Melanie Mauthner; Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill; and Lila by Marilynne Robinson.

Previous winners of the prize include Jim Crace for Harvest, Juan Gabriel Vásquez for The Sound of Things Falling, and Colum McCann for Let the Great World Spin.

Sharma, who also won the £40,000 2015 Folio Prize for Family Life, lives in New York City and teaches at Rutgers University in Newark. “To be acknowledged by people I respect is a strange thing,” said Sharma of winning the International Dublin Literary Award. “I can’t say I fooled them. I feel abashed by this honor.”

Photo: Akhil Sharma. Credit: Jason Clarke.

The awards in poetry were given in three categories: The

The awards in poetry were given in three categories: The