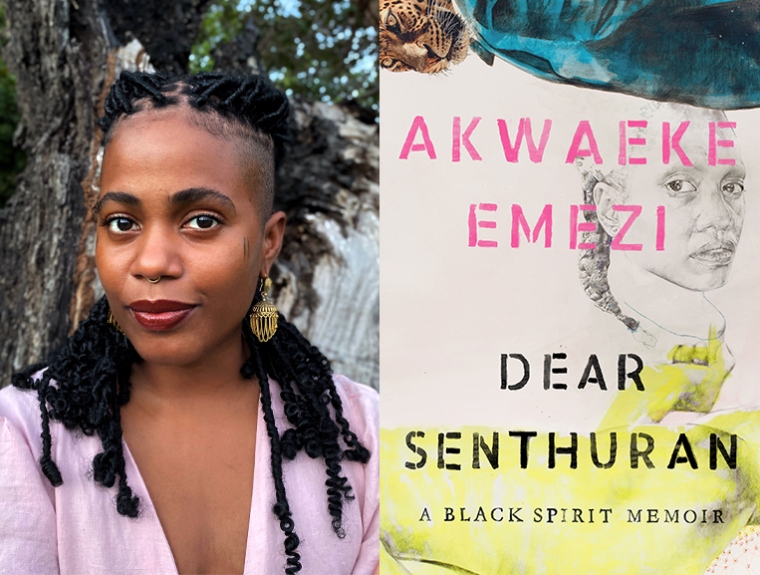

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Akwaeke Emezi, whose latest book, Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir, is out today from Riverhead Books. In Dear Senthuran, Emezi tells their origin story through a series of letters. They reflect on enduring challenges—their struggle with depression, for instance—but also describe coming into their own power. In an early letter, they write, “We can, I promise you, bear much more than we predict.” And in the many letters that follow they chart those moments of perseverance: They undergo surgeries that bring a “shift from wrongness to alignment,” they fend off predatory men who seek to leech off their literary talent and celebrity, and they survive heartbreak. This is a searing and intimate memoir about choosing to live despite the many sacrifices and pains of living. Akwaeke Emezi is also the author of The Death of Vivek Oji, which was a New York Times best-seller and longlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize, and Freshwater, which was shortlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize, a Lambda Literary Award, the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, and the PEN/Hemingway Award. Their novel for young adults, Pet, was a finalist for the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

Akwaeke Emezi, author of Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir. (Credit: Kathleen Bomani)

1. How long did it take you to write Dear Senthuran?

I started writing Dear Senthuran sometime in 2019, but I was in the middle of rolling out Pet, so it wasn’t until that fall that I really sat down to finish it. That time was very much a blur—a lot of the traumatic things I wrote about in the memoir had just happened, so the exact timeline escapes me, but we submitted the manuscript to my editor in January 2020.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

There’s a moment I write about in the memoir, about e-mailing Senthuran Varatharajah, who helped translate Freshwater into German, and how I liked the sound of his name with a dear before it. Composing those e-mails would be the earliest memory tied to the book.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Holding my center. It was hard enough to do while writing, worrying that it wouldn’t be received well, but it was also incredibly difficult to go through the editing process because it felt like my fear that centering a work in Black spirit would come with violent repercussions was proven right. Having to insist on that center and refuse, over and over again, to compromise the work in service of a white gaze was one of the most brutal experiences of my career.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I no longer have any kind of regularity or structure around my writing, unfortunately. I get it in where I can fit it in. I do have to write in my office because my health issues mandate that I now work in an ergonomic setup—farewell to my laptop—but occasionally I write on my phone in bed at night and hope it doesn’t decimate my body too much.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m about to catch up on two of Zen Cho’s books, Black Water Sister and The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water, which I’m really excited about because she’s one of my favorite writers. I will read anything she publishes.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Definitely Chinelo Okparanta. We have so many writers working in queer Nigerian literature now, including myself, but she was the vanguard, and the work she did to open the road for us should be recognized. Her craft is brilliant, and she has an incisive intelligence that I’m excited for even more people to engage with once her next novel, Harry Sylvester Bird, comes out in 2022. It’s a satire of white liberalism, so I think it’s going to ruffle a few feathers, which should be delightful to witness. Chinelo is also an amazing member of the literary community—she’s taught at multiple workshops, advocated tirelessly for young queer Nigerian writers whose lives were quite literally at risk back home, and donated so much of her time to judging awards. I think how you move with your platform as an author is as important as the work you make.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Dear Senthuran?

I learned to respect myself as a thinker. I used to believe that because I wasn’t in academia, I wasn’t qualified to engage with theory, but now I understand how much I am a spirit, not a scholar, and how working in Black spirit theory is my pocket.

8. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

I don’t think I’ll miss anything. After I completed the book last January, I wrote three more books in 2020 and I’m working on another book now, so I’m always in a writing process that has its own particular joy.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

It’s never one particular person. With my manuscripts, I have a community of trusted readers, and they each bring something specific to the table, informed by what their centers are. They are people I think with and write with, so for me, making work is really a community effort.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Octavia Butler said it wonderfully: “First forget inspiration. Habit is more dependable. Habit will sustain you whether you’re inspired or not. Habit will help you finish and polish your stories. Inspiration won’t. Habit is persistence in practice.”