FRIDAY 1:30 PM

Maysville

17 West 26th Street

Avocado egg salad sandwich: mixed greens, crispy shallots

Cobb salad: romaine, grape tomatoes, avocado, hard-boiled eggs, blue cheese

Cajun spiced nuts: garlic, rosemary

Diet Coke, ginger ale

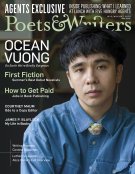

Kent Wolf (Credit: Laura S. Wilson)

My first full-time job in New York, after months of freelance proofreading and temp jobs, was at W. H. Freeman, an imprint of Macmillan. On my first day, when I walked through Madison Square Park to the black skyscraper that held my modest cubicle thirty-seven stories above Madison Avenue, across from the iconic Flatiron Building, my heart did a little somersault. I had made it. It didn’t last long—I left that job after eight months or so—but it was still a great moment. I’m in a hurry as I walk through Madison Square Park this afternoon, but every time I’m in the neighborhood I can’t help but look up at that black building to find the window—not mine, I never had one—through which my former boss, Erika Goldman (now the publisher of Bellevue Literary Press), saw the city’s skyline. After a quick look I pick up the pace, fast-walking a couple of blocks west to the restaurant at which I’m meeting Kent Wolf, an agent at the Friedrich Agency. When he suggested Maysville for lunch, I had to look it up to see whether we needed a reservation. It took me thirty seconds to discover that we would be eating lunch two days before the Southern-inspired eatery and bar that boasts 150 different American whiskeys is scheduled to close, for good. Two questions: Does this mean the place will be empty or crowded, and does the drink menu suggest I’ll get a taste of those inebriating publishing lunches I’d read about?

The first question is answered the moment I step inside: It’s neither packed nor deserted, which is not a great sign for a Manhattan restaurant on a Friday afternoon, hence, I assume, the closing. The answer to my second question takes longer, but in the end: No, those days appear to be over. It’s a couple cans of cold soda for me and Kent, who is from Illinois—he attended Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington—and has a delightfully sly sense of humor. At one point in the conversation he directs my attention to a gentleman wearing an impressive mullet (business in the front, party in the back), a hairstyle we both recognize from our days in the Midwest.

Before moving to the Friedrich Agency, Kent was an agent at Lippincott Massie McQuilkin. He got his start in publishing on the editorial side, at the independent press Dalkey Archive, before working as a literary scout at McInerney International, then moving to Harcourt, for which he was the subsidiary rights manager until 2008, when he lost his job as a result of Harcourt’s merger with Houghton Mifflin.

“This is a very relationship-based business,” Kent tells me after we get settled and I ask him if agents are a particularly competitive bunch. “Whether it’s me or somebody at ICM or somebody at, God forbid, the Wylie Agency, we’re all good at our jobs; we all have the same relationships, but sometimes authors look for different kinds of experience, and some prefer being at a boutique agency like the Friedrich Agency because we’re very hands-on, and you don’t have to go through layers of nameless assistants—you know, like binky urban assistant at icm dot com—to get to me, Lucy Carson, Heather Carr, or Molly Friedrich,” he says, referring to the sole members of the Friedrich Agency team. “But some authors prefer someone in accounts payable who processes their checks, or the allure of a foreign-rights team, or an agency that has their own book-to-film division, and those are things we can’t provide as an agency. But if you look at our track record, it speaks for itself.”

This is true, and among the agency’s impressive roster of clients, one in particular jumps off the page: Carmen Maria Machado, who is represented by the guy sitting across from me.

Just as Julia Kardon reached out to Brit Bennett after reading an essay she had published online, Kent got in touch with Carmen in 2015 after reading a piece she’d written for the Rumpus. Throughout our conversation Kent drops a number of references to literary magazines—Ploughshares, Guernica—that he scours, looking for new talent. I ask him if he can list more of his favorite journals. “If I tell you, then other agents will start reading them,” he says, which makes me think my earlier question about competition among agents was on point. Saturdays and Sundays, he says, one can find him in the reading room of the Center for Fiction, just around the corner from where he lives in Brooklyn, reading stories and manuscripts. He found another of his clients, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, after reading a story of hers in Guernica. Her debut novel, Fruit of the Drunken Tree, was published by Doubleday in July 2018.

Doubleday, of course, is a part of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, which is itself a part of Penguin Random House, the multinational conglomerate formed in 2013 from the merger of Random House, owned by German media conglomerate Bertelsmann, and Penguin Group, owned by British publishing company Pearson.

Carmen’s story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, did not find a home at Penguin Random House, or any of the other publishers comprising the Big Five that currently dominate the commercial publishing market. As a matter of fact, close to thirty publishers, including some small indies, declined before Kent found an editor and a press willing to take a risk on the debut story collection. “Graywolf was our last port of call,” Kent says. “It’s difficult to say what would have happened if Graywolf had turned down the book. Maybe another small press out there would have taken it. The independent presses are the ones that can take risks because they don’t have shareholders to answer to.… The big trade publishers are just notoriously risk-averse, and they’re getting increasingly so.”

The initial response from publishers to Carmen’s debut reminds me of what happened with the first book by Nathan Hill that Emily Forland was unable to sell. “It’s cliché now, but you hear it all the time,” Kent says. “It’s this exact sentence: Stories are hard. And they say it in this soft, apologetic way—gentle. ‘Send us the novel when it’s ready.’ I was in a meeting with a scout, and I was talking about Carmen’s collection, pitching it for foreign sales. And the scout, that was the first thing she said: ‘Mmm, stories are hard.’ She was like twenty-two. What do you know? Your boss says that, so now you’re parroting it. I told her she was never allowed to say that to me again,” he says, grinning.

In the end, Ethan Nosowsky at Graywolf Press bought Carmen’s story collection, and it was published in October 2017. The book that was passed on by the New York publishing establishment went on to be named a finalist for the National Book Award, the Kirkus Prize, the Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction, the Dylan Thomas Prize, and the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. It won the Bard Fiction Prize, the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, the Brooklyn Public Library Literature Prize, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Award. Last year the New York Times listed Her Body and Other Parties as one of “15 remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write fiction in the 21st century.”

“There was a lot of revisionist history going on in New York” once it was clear what all those editors had passed on, Kent says, then adds: “You can write that my eyes rolled so hard my irises disappeared.”

When I ask him to elaborate, he gives me a kind of side-glance, grins, and says, “This is a risk-averse industry, unless they can see an audience for something. That’s why they’re always insisting on comps.” Comps, by the way, is short for “comparable titles,” which are standard ingredients in any query letter or proposal. Agents and editors want to know the titles of some recently published books that have proved successful (but not too successful) and that share some characteristics with what you’ve written. “A book doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” Kent says, repeating what a couple of the other agents said earlier in the week. “So if [editors] can point to this particular recent success, or something that recently won an award or was turned into a movie or whatnot, if they can see that there is an audience for something, then they can more comfortably get behind that.”

On the other hand, writers often hear publishers and editors talking about how they’re looking for the next new thing: something exciting, something they haven’t read before. There is an inherent contradiction at play here, and it triggers one of Kent’s biggest complaints about the industry. “Here is one thing I hate about this business: publishers massively overpaying for debut fiction. It’s the worst. Two or three million dollars for a debut novel and everything else on that publisher’s list gets eclipsed by that book; they put all of their efforts behind it,” he says. “They circle their wagons around one, two, three books a year, and everything else is getting lost. This is not a sustainable model. It’s bad for publishers, it’s bad for authors, it’s bad for readers.”

Carmen’s second book, a memoir, In the Dream House, will be released by Graywolf in November, and despite the early rejections of her debut, it is difficult to see how her career would have been launched any better at one of the bigger publishers. “With Graywolf, it’s a smaller list, and the attention they pay to each book is noticeable,” Kent says. “What’s nice for an author being published by a press like Graywolf is that they’re more part of the process. And I think authors are given more agency, or at least they are able to be part of decisions in a way that a [larger publisher] couldn’t offer because of the layers of bureaucracy.”

![]()

MONDAY 1:00 PM

Taylor Street Baristas

28 East 40th Street, between Madison and Park Avenues

Granny’s chopped salad: romaine, cucumber, avocado, tomato, feta, smoked salmon

Smoked tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich

Nishi Sencha tea, filter coffee

I was warned that Taylor Street Baristas would be loud, and as I make my way through Grand Central Terminal and walk two blocks south on Park Avenue to the specialty coffee shop and café, I take Emily Forland’s advice to hope for the best and expect the worst. Unfortunately, my fears are realized when I walk in the door. I believe clamorous is the word. So many people talking so close to one another (the Midwesterner in me will never get used to tables positioned this close) that I worry I won’t be able to hear my lunch companion, Marya Spence, an agent at Janklow & Nesbit. As I wait for her at a corner table in the second-floor dining room, music is added to the din. I would be annoyed if not for the playlist (sweet sounds of the 1970s, “Running on Empty” by Jackson Browne, followed by Steely Dan’s “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” offer an appropriate soundtrack for this rainy day), and soon enough my ears adjust and Marya arrives.

Having studied literature at Harvard, followed by an MFA in fiction at New York University, during which she had paid internships at the New Yorker and Vanity Fair—she also wrote reviews for Publishers Weekly and taught undergrads—Marya seemingly could have had her choice of careers in the editorial or academic arena. Toward the end of her time at NYU, she began to look into teaching, a profession that was familiar to her. (She grew up on college campuses; her father is a prize-winning professor and administrator who taught at schools across the country). But while Marya was applying for adjunct teaching jobs, the writer David Lipsky (Although of Course You End Up Being Yourself: A Road Trip With David Foster Wallace) suggested she look into agenting. “I really had no idea what agenting was at that time,” she says, but Lipsky knew someone at Janklow & Nesbit, an agent who specialized in young adult fiction and is no longer with the firm, so she sent her résumé, which floated down the hallway to another agent, PJ Mark, who brought her in for an interview. “I came in, wrote an editorial response on a manuscript, and we were off to the races,” Marya says. She started as PJ’s assistant while doing what many assistants do: try to build their own list of clients. “I was working on some projects of my own…doing that thing young people have to do in publishing, which is working double triple time. I was my boss’s assistant during work hours, and then I would stay late editing some manuscripts that I hadn’t formally signed yet. But that’s how you get your foot in the door.”

One of the books that landed on her desk in those early days, in January 2015, to be precise, was Goodbye, Vitamin, a novel by Rachel Khong, then senior editor at Lucky Peach, the irreverent food magazine that would shutter two years later. The novel, about a thirty-year-old woman who returns home to Southern California for Christmas and ends up staying to care for her ailing parents, made an immediate impression.

“I read Goodbye, Vitamin overnight, and I cried on the subway and I cried at my neighborhood bar, where I would sit in the corner and they would pour me tea—it was very romantic, my life then,” Marya recalls. “And I walked into PJ’s office and said, ‘Look, I haven’t asked to sign anyone yet, particularly one that came to both of us, but [she pauses] this is my book. It has to be.’ And PJ was drowning, as I am now, and was like, ‘Please, you have more than my blessing.’”

So Marya sent Rachel an editorial letter—she calls them love letters—in which she put all of her thoughts and visions and desires for the book, comparing her work to Renata Adler (Speedboat) and Jenny Offill (Dept. of Speculation), and explaining some of the editorial work she thought the manuscript needed, including tightening the pacing in some places and building up some of the characters. “I will admit I’m a sucker for romance or a crush story, so I wanted that to be built out a little bit more too,” she says.

Rachel happily agreed, and for the next ten months or so, the agent and author worked together on the manuscript. Meanwhile, Marya made her first sale: Jaroslav Kalfar’s Spaceman of Bohemia to Ben George at Little, Brown, in a six-figure preempt—not a bad way to start an agenting career. When Goodbye, Vitamin was ready for submission, it too received an “overwhelming response,” attracting more than a dozen interested editors. Before the auction, Marya scheduled what she describes as “a week of back-to-back, on-the-dot forty-five-minute phone calls” between Rachel, who lives in San Francisco, and her suitors.

I ask Marya what exactly happens during these kinds of phone calls—or typically, if the author is in New York, in-person meetings—before an auction begins, and whether the conversations are primarily for the editor’s benefit or the author’s. “First and foremost it’s for the writer,” she says. “Editors’ responses to a manuscript can range from ‘I’m interested but with some qualifications,’ in which case a talk is really important for them to just speak directly and get a sense for each other’s styles and personalities, to ‘I’m just freaking out, I’m losing sleep over this book, and I just want to tell this person how much I’m dying to work with them,’ which is also good for a writer to hear.”

In Rachel’s case the responses were similarly varied, so it was important for her to get a sense of where each editor stood before the auction began. As a result of one of the phone calls, an excited editor made a preemptive offer. “With all of the interest, we didn’t take it,” Marya says. “It was a really nice preempt from an amazing editor and house, but I wanted Rachel to know where some of these other houses and editors were coming from.” Instead Sarah Bowlin, a senior editor at Henry Holt, won the auction and the rights to publish Goodbye, Vitamin.

Fantastic news, but then what? I’ve always been curious about the moments, days, and weeks following such a momentous decision. Here’s a debut novelist whose life has just been changed by a series of e-mails and phone calls on the other side of the country. What’s the next step?

“The next step is getting on an e-mail chain together, and there’s lots of exclamation points,” Marya says. “I think it’s really important to celebrate. This is a moment where everything has gone right. Cherish that.” This is solid advice. But an agent doesn’t just raise a glass, then hand over the keys and wish the writer well. There are a number of things that require her attention: The finer points of the contract need to be settled—the formats and markets in which the book will be published, subsidiary rights, payment schedule, due dates, options, and so on—and the publisher’s contracts department likely needs a little nudging. And then there’s getting everyone together—the author, the editor, the publicity and marketing team—so they can draw up a game plan for publication.

Still, on some level there is a handoff that happens naturally after the author and editor have been introduced. “I like to be looped in on everything, but I also want writers to have direct relationships with their editors,” Marya says. “As much as I would love to be a part of every step of the editorial process, I just can’t be, so they need to get comfortable as soon as possible. I think of it sometimes like a relay race. Up until that point, for months or maybe years I’ve been working with my writer on a super-familiar basis; now the ball is more in the editor’s court, and they might step into that role of editorial and creative collaboration.”

But then sometimes, as was the case with Rachel, the unexpected happens: Sarah Bowlin left Holt. As a matter of fact, she left editing altogether: She moved to Los Angeles and is now an agent at Aevitas Creative Management. “So then the book was reassigned to Barbara Jones, who is wonderful,” Marya says. “I could think of no better editor to take up the mantle than her. She had said that she was the first person to raise her hand to take it on because she read it and cried during submission.”

Marya calls the departure of an editor mid-process “very disruptive,” but in this case it didn’t spell disaster. The publisher was already fully behind the book, and it had already been edited, but there were still many things to be done before publication, including finalizing the cover. Marya stayed on top of the situation. “I think authors need to hear, ‘Don’t worry, I’m on top of them. I’ll make sure that these balls don’t get dropped.’”

Agents, of course, are good at juggling, and after Goodbye, Vitamin was published in July 2017, it was named a best book of the year by nearly a dozen major publications, including O, the Oprah Magazine; Vogue; Esquire; Entertainment Weekly; and BuzzFeed. It went on to win a 2017 California Book Award and was a finalist for the Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction.

I ask Marya if she has any advice for authors in the middle of the publishing process, who may be juggling a bit of anxiety themselves. “Recognize that there will always be surprises along the way,” she says, “and know that we’re on your team.”