Last spring, while touring with my new essay collection, Shelter and Storm: At Home in the Driftless, I accidentally assembled an anthology that changed the way I look at literary events. The project began with a bookmaking workshop I had attended on the Saturday before my essay collection’s launch. Eight students and our teacher, a professional bookbinder, met in a small, chilly classroom in the corner of a factory turned makerspace in Madison, Wisconsin. The other students arrived with concepts and intentions. One man was making a journal for his college-age niece. He chose beautiful scarlet book cloth and embossed her initials in gold on the cover. Another woman was making an emerald and violet volume for her memories of a trip to Ireland. In the crush of prelaunch publicity, I’d neglected to imagine a purpose for my homemade blank book.

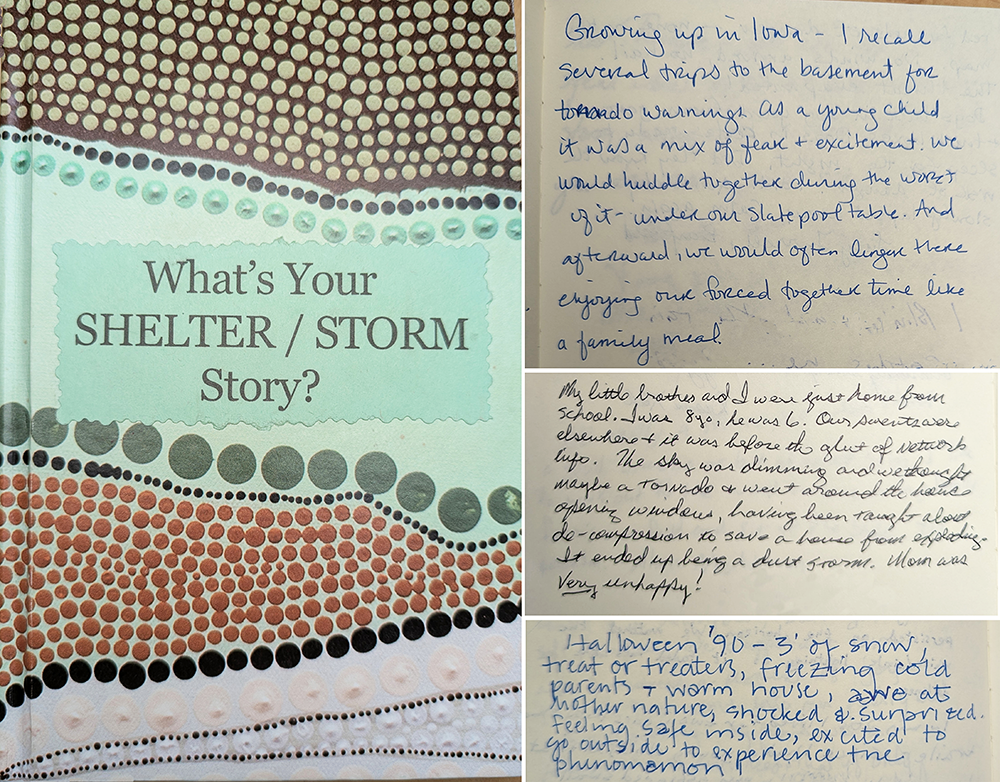

Moments before leaving the house for the workshop, however, I grabbed a wallpaper sample I’d ordered long ago. I hoped it would make suitable book-cover material. Featuring an Aboriginal design by Kija Bardi artist Kamilya Lowana-White, the wallpaper depicts what looks like rolling hills composed of green, brown, and henna-colored dots. According to the product description, “Each dot represents a footprint and, cumulatively, the creation of journey track[s] over time.” If I’d read that before the workshop, I didn’t remember it. But the design’s echoes of a landscape spoke to me. Shelter and Storm collects my tales of trying to live lightly on the land while facing climate-change disasters in rural Wisconsin.

When the instructor asked about my project, I improvised: “It’s a guest book. For my book tour.” A memento, I thought. I would bring it to readings and ask people to sign it.

No, I decided as I measured, razored, pasted, and pressed wallpaper onto book boards. I wanted more than people’s signatures and good wishes. I wanted to read their stories of finding shelter and weathering storms.

On my mind was another story-collecting project, one that friends and I from the Driftless Writing Center in southwest Wisconsin had initiated after one of the worst floods in history engulfed our region in 2018. Recognizing the power of storytelling to help people heal from trauma, we invited hundreds of flood survivors to tell us what they had experienced. As I recorded survivors’ stories, I was honored by their trust and astonished by their strength. The witnessing changed me. I had survived the flood too. After a dam crumbled, a 500-million-gallon reservoir drained downstream, toward our house. Water filled our valley and marooned us, stopping just twenty feet from our back door. Only after hearing what others had endured could I acknowledge my own anxiety—and resilience—that the disaster left me with.

The writing center published excerpts from survivors’ narratives in a booklet we distributed at a community gathering where we also invited people to share their stories aloud. As we’d hoped, community members began to feel more empowered, less alone. The project amounted to not only a record of an event in a particular place and time, but also a testament to collective healing.

Five days after the bookmaking workshop, at my essay collection’s launch party, I stood before an auditorium filled with friends and welcomed them to add their stories of shelter or storm to my homemade book. Participating was optional, I emphasized. Writing quality didn’t matter. I was grateful for anything they chose to include.

During the Q&A following my presentation I glimpsed the book circulating through the crowd. But I lost track of it as I was signing copies of my essay collection. Thankfully, someone found it and set it with the rest of my things at the end of the evening.

I introduced and passed around my homemade book at seventeen subsequent readings. My guidance grew clearer. I stopped calling it a guest book or a book-tour memento. I reiterated that any tale of calamity or refuge had merit. If people looked perplexed or hesitant, I tried a simpler ask. “I’d love to read your story.”

Not everyone contributed, but many did. People wrote while I read aloud, answered questions, or signed books. Some filled more than a page. Some flipped back to previous pages to read what others had written. A few told me more stories after the event—about the loss of their family farm, or a dead, pregnant garter snake they’d found with thirty-eight babies inside it, or the alarming disappearance of bumblebees in their county. My request for stories seemed to heighten engagement at my events, although that hadn’t been my aim.

Given the busyness of book promotion, months passed before I found time to read all the entries. When I did I was touched by the heartfelt congratulations and compliments. I was amused that every contributor but one had added to the book in order, filling the next available page rather than jumping ahead. Some left off their names, while others signed and dated their entry and named the locale. Without those details, though, I could usually tell from the incidents they described where people had been when they wrote.

Then, because I relish data, I tabulated, categorized, and analyzed the book’s contents. Nearly half of the 176 entries—with higher proportions in my current or previous hometown—were general good wishes or greetings. For some it was an opportunity to let me know they were present when they hadn’t said hello personally. Some reminded me that we had worked together decades ago or that they had taken one of my classes. One recalled surviving a storm with me. In another entry, an author promoted her own book and website.

I was most interested, though, in the personal descriptions of storms and shelters. What had people survived? What stood out from those difficulties? Where had they felt safe?

As when I listened to the flood survivors, I was grateful for and captivated by the narratives people shared in my blank book. A common thread is that childhood storms are much less terrifying in retrospect. Memories of tornadoes in particular evoke excitement or nostalgia.

Some entries are humorous. A few occur in distant places, where the authors had grown up, but most reflect the character of the Upper Great Lakes region, where my readings took place. Tornadoes, floods, snow, and ice storms are prominent (while some storms, as in my essays, are figurative). Farmhouses, kitchens, and cellars provide refuge.

What comes to mind for me are the times our family spent in the basement when tornadoes were looming around us. When I was a small child, those were scary nights, but I also look back on them fondly as family bonding times when we played games and just spent time together.

My little brother and I were just home from school. I was 8 years old, he was 6. Our parents were elsewhere, and it was before the glut of network info. The sky was dimming and we thought maybe a tornado and went around the house opening windows, having been taught about de-compression to save a house from exploding. It ended up being a dust storm. Mom was very unhappy!

I moved to the driftless after I got divorced and left my farm in Illinois. I felt a resonance with the ups and downs of the topography mirroring my own life experience. I was welcomed with the warmth and generosity of local people who instantly grounded me and helped give me a sense of home. Forever grateful to the driftless for welcoming me during a time of transition.

Halloween ’90 – 3' of snow, trick or treaters, freezing cold parents + warm house, awe at mother nature, shocked & surprised. Feeling safe inside, excited to go outside to experience the phenomenon!

Three writers mentioned the dark clouds gathering and thunderstorm warnings issued even as they listened to me read. A handful said that books and bookstores were their shelters in difficult times. About 20 percent of the stories collected in the book portray the writers finding shelter during a storm. After I reread those, what stood out to me is how people equated shelter with the presence of those they cherished. Shelter was never only a structure. It was the reassuring presence of family, friends, or kind strangers.

Growing up in Iowa—I recall several trips to the basement for tornado warnings as a young child. It was a mix of fear + excitement. We would huddle together during the worst of it—under our slate pool table. And afterward, we would often linger there enjoying our forced together time like a family meal.

A simple collective shelter—driving in a storm on the highway and pausing with other cars beneath the underpass until the worst of it had blown over. Even though we couldn’t see each other, the comfort of others was there!

Shelter and storm stories, I started to realize, are love stories. That same message emerges from the essays in my collection. As one reviewer pointed out, they are “a love letter to the joys and griefs of living on the land.” They also depict my love for my partner, David, our neighbors and friends, and the land’s inhabitants, human and animal, past and present. I hadn’t planned that when I wrote the book. Yet inevitably it’s the larger story that all our tales of shelter and storm reveal.

The cover of the author’s handmade book, which now holds a collection of handwritten personal narratives (right) by attendees of her book tour readings. (Credit: Tamara Dean)

I believe in the power of collective storytelling to create a chronicle whose significance is greater than the sum of its parts. All our personal narratives matter. And in this time of climate upheaval, we benefit from sharing how we have confronted and survived disasters—together.

Svetlana Alexievich, the Nobel Prize–winning author who has gathered, edited, and published stories from Russians who survived war, Chernobyl, and political turmoil, writes: “I believe that in each of us there is a small piece of history. In one, half a page. In another, two or three. Together we write the book of time. We each call out our truth…. And it all has to be heard, and one has to dissolve in it all, and become it all.”

I regret that I can’t decipher two authors’ handwriting in the book. But I believe that even their truths are contributing, if covertly, to a greater whole.

Half filled now, the anthology of stories has become a memento of my book tour, too, as I had first conceived it during the bookmaking workshop. It answers the promise of its cover image, marking the cumulative tracks of my journey as I crisscrossed the Midwest, reuniting with old friends, making new friends, and exchanging stories.

It is also the account of a shared journey. We readers and writers are fellow travelers huddled under a bridge or in a basement. With care, during life’s travails, we make shelter for one another. And if stories are gifts from the heart, as I believe, then collaborating on this homemade book amounts to a communal act of love.

I’ll keep bringing it to events and calling it a story collection, not a guest book. I’ll highlight its power as a chorus of voices about our contemporary crisis with ideas for optimistically moving forward together. And I’ll urge people to write legibly, so their stories can be read.

Tamara Dean is an author, instructor, and audio producer whose latest book, Shelter and Storm: At Home in the Driftless (University of Minnesota Press, 2025), invites readers to consider how we tend the earth in times of uncertainty, what we owe our neighbors, and ways we thrive in community. Her award-winning essays have appeared in the American Scholar, the Guardian, the Georgia Review, Orion, the Southern Review, and elsewhere. Her website is tamaradean.media.