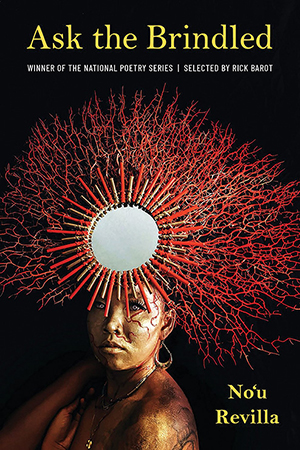

No‘u Revilla

Ask the Brindled

Milkweed Editions

(National Poetry Series)

…we listen to grandmother talk about shedding.

And for the dark pit of her mouth, we have reverence.

—from “About the effects of shedding skin”

How it began: Hawaiians have been writers and lovers of poetry for centuries, and I wanted to show up for my ancestors. I also wanted to show up for other queer ‘Ōiwi women who know how to jimmy-rig care and connection out of wreckage. Our abundance is worth a lifetime of poems.

Inspiration: There are two central figures in Ask the Brindled: my grandmother and the shapeshifters I come from, who are called mo‘o. In Hawaiian culture, mo‘o are water protectors who take the form of lizards and women. I’m lucky to have access to the different kinds of stories that surround these figures, in oral traditions and written texts, in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i and English, in family knowledge and historical archives.

Influences: Haunani-Kay Trask is a beloved ʻŌiwi poet and activist. She taught me how to swallow colonizers while I build what she called a “slyly / reproductive” life.

Writer’s block remedy: I go to the water, whether river, ocean, or muliwai. E ola i ka wai.

Advice: Practice gratitude and uplift others. Earning your community nourishes your writing.

Finding time to write: I’m learning how to say no to things in order to protect what I say yes to, like my writing. Indigenous women are often expected to say yes to everything, as if we aren’t taking care of our people unless we’re on the brink of burnout. I’m learning how to say no like it’s a complete sentence—because it is. I believe in generative refusal.

Putting the book together: Ask the Brindled begins with two seeds and ends in a grove. My dear friend Rajiv Mohabir, an intelligent and generous writer, taught me a lot about shaping a manuscript. This book would not be here without his guidance.

What’s next: Collaboration is an important part of my practice. Right now, I’m lucky to be dreaming and creating alongside two other Indigenous Pasifika women who are visual artists.

Age: 36.

Residence: I was born and raised in Wai‘ehu on the island of Maui, and I currently live in Pālolo Valley on O‘ahu.

Job: I am an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Hawai‘i in Mānoa.

Time spent writing the book: Most of the book was written between 2018 and 2019. The next two years were spent revising and being honest about what I wanted to do with the work.

Time spent finding a home for it: I submitted the manuscript in March 2021 and heard the good news from the National Poetry Series in August 2021.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: Read Julian Aguon’s lyric essay, No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies (Astra House)!

Ask the Brindled by No‘u Revilla

![]()

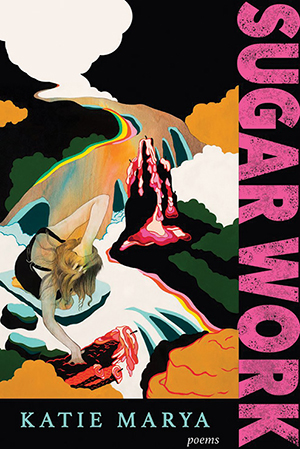

Katie Marya

Sugar Work

Alice James Books

(Alice James Award Editor’s Choice)

There is no country for me except the body.

And my mother’s body.

—from “Exaltation”

How it began: Oh, who knows! My lived experience. A burning desire. I know I got serious about the oldest poems in this book while I was teaching high school Spanish from 2012 to 2015. I had been writing in my closet when I could find the time. To nudge myself toward some kind of self-care during my second year of teaching, I took a poetry class in the evenings at Austin Community College. I compelled myself to write this book—and my fellow, beloved writers from that class compelled me.

Influences: In terms of poetic form, Natasha Trethewey. Reading her work taught me everything I knew about fixed forms at the time. Louise Glück and Lorna Dee Cervantes are the poets I read over and over while writing Sugar Work.

Writer’s block remedy: Food prepared with care. Going outside. Riding my bike. Wanting to leave a legacy of thoughtfulness and artistic knowing for my niece and nephews. I listen to a lot of music. I trust that what I do every day contributes to the work of writing. I don’t worry much about the impasse—it is a signal to give things time.

Advice: Get out of your own way. Spend time with people you love. Work hard. I maxed out a small credit card on submission fees. If you can, don’t pull any punches about what it costs to get a book of poetry out there.

Finding time to write: I have been in a PhD program the last six years, which has allowed me to exist alongside brilliant writers. Even in my busiest semesters, being a part of an artistic community has felt like “time to write.”

What’s next: I am working on a second manuscript about grief. It hinges on a study of the history of drumming, the drum kit, and fentanyl. My dad is a drummer. It’s part elegy, part homage to the artistic collaborations we could have had but didn’t. It’s a love song for my brothers.

Age: The tail end of 34.

Residence: Lincoln, Nebraska.

Job: I am a graduate student right now. My hope is to land a tenure-track professorship in an English department sometime soon, though I know the market is rough. I have taught some form of language and writing since I was 23. I started as a high school Spanish teacher. Of course, I’ve worked all kinds of odd jobs, too. Right now I work a few hours a week at a bicycle shop to make ends meet. It’s a beautiful place.

Time spent writing the book: I started in 2014, so eight years altogether.

Time spent finding a home for it: Three years.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: Earth Room (Changes Press) by Rachel Mannheimer. I am looking forward to Brother Sleep (Alice James Books) by Aldo Amparán.

Sugar Work by Katie Marya