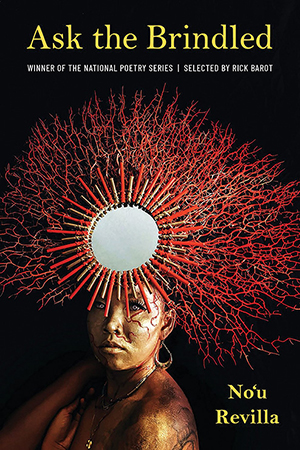

The feeling of green. Shapeshifters. Pina Bausch. These are among the sources of inspiration the poets in our eighteenth annual feature shared regarding their yearslong journeys toward the publication of their debut collections. Each of the following ten books offers a new lexicon for us to explore the human experience, where language is stretched, and a poem can become “a ghost, caught between reality and longing,” as James Fujinami Moore puts it. Expanding the concept of what constitutes a poem, Maya Salameh’s How to Make an Algorithm in the Microwave transforms poetry into coding, data, a mathematical function, part of software; Courtney Faye Taylor’s Concentrate utilizes collage, photographs, and found text to hold polyphonic states of feeling and thinking; and No‘u Revilla gifts us vertical language with words falling down the page like droplets of rain and growing up like saplings in Ask the Brindled. In Earth Room, Rachel Mannheimer writes an ekphrastic book-length poem with tonal aplomb; in Prescribee, Chia-Lun Chang tackles the immigrant experience with ferocity and vulnerability; and Nicholas Goodly’s Black Swim pours forth lyric poems both magical and muscular.

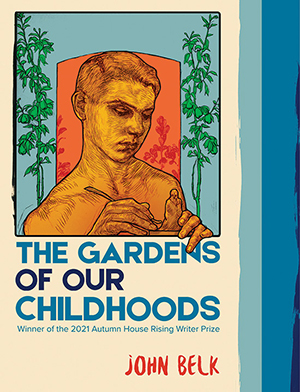

The breadth of content covered in these collections mirrors the equally wide range of tones and forms. Shelley Wong celebrates queer women of color in As She Appears; John Belk parses masculinity through the lens of pro wrestling in The Gardens of Our Childhoods; Katie Marya meditates on motherhood, marriage, the female body, and desire in Sugar Work; and James Fujinami Moore reckons with brutality, death, and tenderness in indecent hours. These authors decenter overly accustomed narratives by (re)centering their own perspectives on living, their personal and cultural histories, their chosen and biological families. “To write of being and not merely being against,” as Wong says, is the overarching project at play.

For some of these poets the path to publication was a matter of four months, while others landed with their press after six years and thirty-three tries. Though the timing may be different for each writer, several of them mention literary community as the backbone of their collections and writing practices, and dance, allowing the improvisational language of the body, as the impetus for poetry and the cure for burnout. Nature and its untamable ways also prove fertile ground for these poets. Belk draws inspiration from how “[g]ardens are nature we try to curate and script, but it never really goes according to plan—wildness always finds a way in.” In this vein, Taylor recommends fellow writers “act wild on the page. Don’t erase the risks your creativity wants to take.” In honoring the beauty of being and engaging in life’s complexities and multifaceted truths, its aches and pleasures, we present ten shimmering poets whose influences, pathways, and advice are as nourishing and distinct as their debut works. Chang’s recommendation for writers looking to unleash their creativity: “Write something honest and rebellious. Be vulnerable and miserable. Allow the language to thrive outside your body.”

Courtney Faye Taylor | Maya Salameh

John Belk | James Fujinami Moore

No‘u Revilla | Katie Marya

Chia-Lun Chang | Nicholas Goodly

Rachel Mannheimer | Shelley Wong

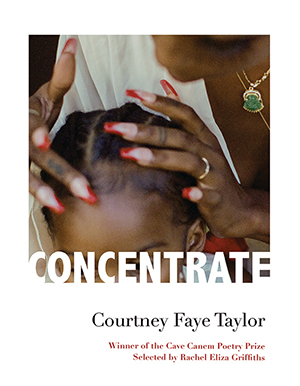

Courtney Faye Taylor

courtney_faye_taylor_final_white.png

Concentrate

Graywolf Press

(Cave Canem Poetry Prize)

I crept to mom ’n’ pops where bells above doors snitched to mention my entrance.

But I tolled them bells. I was toys to be bothered. I had made such toyish mistakes.

In any Black sentence, you’d love nothing more than to had made no mistake.

—from “So far”

How it began: Most of the poems in Concentrate were initially part of a different manuscript about my upbringing. I don’t think I was ready to write that book, but I was happy with the poems I had in there about Black girlhood. I took those poems and started building a new manuscript around them. At the same time I was thinking about the murder of Latasha Harlins, who was killed by a Korean shopkeeper during a dispute over a bottle of orange juice in 1991. I can’t remember when I first heard about the killing, but however Latasha came into my consciousness, it was in a secondhand way. Latasha would’ve been forty-seven years old this year. There’s something so heartbreaking about that math. The tragedy that she died at fifteen but also the tragedy that she was refused forty-seven, refused the long, sweet trek to Black womanhood. I had all these wonderings about Latasha, wonderings about the risks and wounds of Black girlhood, wonderings about myself.

Latasha then led me to considerations of Black and Asian American relations. My first understanding of tension between our communities was in the context of Black beauty supply stores. It was easy to understand white racism, but coming to terms with white supremacy between communities of color was difficult. I was curious about this dynamic and what’s behind it, what’s fueling it, what’s misconstrued about it.

Inspiration: I handle complex subject matter in Concentrate—including the manifestation of white supremacy between communities of color and the precarity of Black girlhood under sexually and racially charged violence. While writing the book I sometimes felt like what I needed to say about those concepts couldn’t be held by a traditional poem. The emotion was too big or too oddly shaped. My remedy was an interdisciplinary approach, calling on essay, playwriting, photography, and collage as coconspirators to the poetry. Embracing different forms meant Concentrate became polyvocal, speaking various artistic tongues to convey those unwieldy truths. So I’d say form experimentation was a big inspiration for the writing.

Influences: In 2016 Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon visited my MFA program to give a talk. She opened with this quote from Toni Cade Bambara: “What are you pretending not to know today, Sweetheart? Colored gal on planet earth? Hmph know everything there is to know, anything she/we don’t know is by definition the unknown.” I’m thankful to Van Clief-Stefanon for bringing that passage into my life. I keep it close. It reminds me that my knowledge as a colored gal is infinite, that I’m already equipped with truth.

When it comes to the influences for Concentrate, there’s Anna Deavere Smith, playwright of Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992. It’s a one-woman show based on interviews Smith did with folks who experienced the L.A. uprising. There’s also Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, which helped me consider the ways Black and Korean American women navigate a similar terrain of vulnerability in this country. Then Dr. Brenda Stevenson, author of The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the L.A. Riots. I can’t think of another book that dedicates as much attention and care to the details of Latasha’s life prior to the morning of March 16, 1991.

Concentrate enters a lineage of poetry collections like Bodega by Su Hwang and Imperial Liquor by Amaud Jamaul Johnson. These poets write with such vulnerability, reflecting on the cultural impact of Los Angeles in the 1980s and 1990s.

Writer’s block remedy: I love reality TV—The Real Housewives, Married at First Sight, etc. Sometimes I do this exercise where I’ll listen to a scene from one of those shows and start writing down what I hear—not every word, but the words and phrases that seem interesting. What I end up with is this jumbled, often senseless transcription of dialogue. That found language has given me some unique images and lines that conjure poems.

Advice: You want your work in caring hands. I’m grateful for the thoughtfulness Graywolf has shown my book and the support they’ve offered my career. Early on I tried to figure out which presses might be best for my work so I could focus on submitting to those places.

Submit your manuscript even if it’s not “done.” If it gets picked up, you’ll have time to edit.

Play. Experiment. Act wild on the page. Don’t erase the risks your creativity wants to take.

Finding time to write: I write in pockets of the day where I have free time in my schedule. I’ll go to a coffee shop for a few hours, sit at a table by the window with a vanilla latte or an iced chai (a new favorite). Most of my writing days focus on revision. I’ll go through old poems and see if I have something beneficial to offer them. Eventually, I’d like to start a practice where I sit down to write something brand new on a consistent basis. I tend to only write new things whenever the feeling strikes. It’s an unpredictable spark. But when it happens, I drop whatever I’m doing to capture it. I never silence that impulse.

Putting the book together: When Concentrate won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, it’s organization was really scattered and haphazard—intentionally so, because I wanted the book to read as a clash of inseparable ideas. In a way, I’m asking the reader to “concentrate” in the midst of this wild collage, to trust where I’m leading them, to release the expectation of cohesion because none of this—the beasts of white supremist violence—is sensible or easily digested.

But at the same time, I still needed the book to be readable. My editors, Chantz Erolin and Kiki Nicole, helped me maintain the collage while instilling some order. I added more section titles since there aren’t poem titles. I added the section “Four memorials,” which was an opportunity to step back from the collage feel and speak straight-forwardly. I think of this as the moment where I’m looking in the eye of the camera. So, the editorial process was about the balance of wildness and order.

What’s next: A couple months ago, I found a copy of Grambling State University’s 1991–1992 yearbook at Savers Thrift Store. The yearbook opens with a mention of Rodney King and the L.A. Riots. Having just finished Concentrate, it felt particularly meaningful to come across this artifact. I used images and text from that book to create a visual poem. I’d love to do a series of visual poems based on historically Black colleges and universities’ yearbooks, so I’m on the lookout for those.

My mom is digitizing all the home videos from my childhood, so I’m getting to see this footage for the first time. She just shared a video of me at six-years-old, dressed as Glinda the Good Witch. I can already anticipate the kind of writing these videos may bring out of me.

Though Concentrate has personal elements, it’s largely me analyzing events that happened two thousand miles away and two years before my life began. Maybe my next book will be more of a direct look at myself. Maybe I’ll return to that manuscript I wasn’t ready to write.

Age: 29.

Residence: Kansas City, Missouri.

Job: I’m a senior writer at Hallmark Cards and I also teach creative writing.

Time spent writing the book: I’ve been considering the topics I address in my book since I was a child. Because thought, feeling, and experience are where a poem begins, the beginnings of this book go back that far. I think the oldest poems in the book are from six years ago. Those are poems I wrote during my MFA years.

Time spent finding a home for it: I submitted Concentrate for the first time in 2019, but prior to that I had a different manuscript that I started sending out in 2017.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: All the Blood Involved in Love (Haymarket Books) by Maya Marshall. Her lyric meditations on motherhood—both the choice to mother and the choice not to—feel timely, especially as women continue to be unprotected in decisions of motherhood. The book considers the meaning of desire and freedom, and who has access to them. A favorite line, from the poem “An Abortion Ban”: “A fetus without lungs is an unlucky horseshoe. / A fetus in a homeless woman is an empty pillowcase.”

Muscle Memory (PANK Books) by Kyle Carrero Lopez. Kyle’s poetry is so alive and sonic. The chapbook handles the full menacing scope of anti-blackness without flinching, with the kind of language that stares you dead in the face. A favorite line, from the poem “Petty”: “If it’s petty / to take what should already be free, / is pettiness a small revolution?”

I’m excited to read Bluest Nude (Milkweed Editions) by Ama Codjoe. Every poem I’ve seen posted online from this collection has blown me away.

Concentrate by Courtney Faye Taylor

![]()

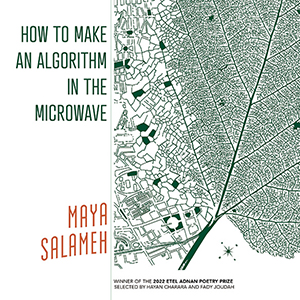

Maya Salameh

How to Make an Algorithm in the Microwave

University of Arkansas Press

(Etel Adnan Poetry Prize)

don’t make

an amenable

saint.

—from “How to Lazarus Yourself”

How it began: I was drawn to writing this book out of a deep curiosity about our technologies, especially the ways we are creating such intimate relationships with supposedly inanimate objects. The phones we lie next to every night collect our medical information, the pills we take, the politicians we believe, the sad poems in our Notes app, our porn, and food preferences. All our lives, interests, and dreams are becoming part of an unwitting archive—but a computer is not a stone pallet simply holding that information; it’s monetizing it. So how do we begin to stare back at these appliances of the surveillance state? How do we begin to say, the computer is not infallible either, the algorithm is riddled with bugs we can pick at and opinions that can be rewritten. Once I started thinking about what it might feel like to play with technological forms in more rambunctious ways, to impose play on the algorithm, it felt like an important space of freedom to explore. And from there came the book.

Inspiration: Some sources of inspiration have included: creeks, chamomile cigarettes, the feeling of green, blinds that don’t come down right, bugs in software updates, bugs in the corners of wooden sheds, spiders in August, August, my sister, blue-light-tinted sleep, my grandmothers, brown suitcases, Amy Winehouse, small pieces of the Bible I’ve read, structure, the defiling of form, white peaches, red grapes, and ceramic soup spoons.

Influences: Some of the poets who have deeply informed my work are Safia Elhillo, whose bilingual experimentation and languaging made me less afraid to explore my tongues; Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, whose collection, Beast Meridian (Noemi Press, 2017), inspired me to play more with what we deem scientific knowledge; Franny Choi, whose delightfully gory, cyborg-woman writing helped me find the beauty and divinity in the uncomfortable; and Khadijah Queen, whose collection I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On (YesYes Books, 2017) remains one of the closest dictionaries for my experience of womanhood I’ve ever encountered.

Writer’s block remedy: I turn to my friends, my television, and my life. I turn away from the poems, so they feel less stage-shy, and turn to writing everywhere else: prose, journaling, even song. In moments of burnout I love being able to access my other mediums, especially dance. I find my body often knows the language my mouth is still forming.

Advice: Don’t force the book to be perfect before you let it see the world. Send it places; that travel will shape it in turn.

Finding time to write: In the corners of time my work allows me, and capitalism forgets—on the bus, in line at the grocery store, and before I go to sleep.

Putting the book together: This was such a difficult process for me because I wanted each poem to fit well in its neighborhood of fellows. I ended up printing out the whole manuscript and moving poems around on the floor for three hours until I’d put together a configuration that felt like it sang well together.

What’s next: I’m resting, allowing myself to digest the completion of this first baby, and letting my poems return to me slowly and with leisure.

Age: 22.

Residence: Champaign, Illinois.

Job: I’m a graduate student!

Time spent writing the book: About a year.

Time spent finding a home for it: Four months.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: How to Identify Yourself With a Wound (Kallisto Gaia Press) by KB and Return Flight (Milkweed Editions) by Jennifer Huang.

How to Make an Algorithm in the Microwave by Maya Salameh