Every year since 2005 we have highlighted a group of writers who have published their first full-length poetry collections in the prior twelve months. We ask the poets to describe what set their books in motion, what keeps them returning to the page, and how they live as writers. When we inquire how long it took to write their books, every year several reply, “My whole life.” And this makes sense—a book is not the work of a moment or simply a product of the time the poet was setting down words on the page. Many of the poets have been writing poems—or the poems that helped them get to the ones in their books—for decades. Many have been fashioning their relationship to language, their manner of responding and speaking through and about their concerns, their entire lives. They have been going through, as poet Taylor Johnson says, “the process of articulation and learning my own language.” Or, to use Chad Bennett’s words, the “eccentric, vitalizing process” that makes up “a life in poetry.”

Clockwise from top left: Anthony Cody, Taylor Johnson, Leila Chatti, Destiny O. Birdsong, Chad Bennett, Roy G. Guzmán, Tommye Blount, Chessy Normile, torrin a. greathouse, and Claire Meuschke. (Credit: Eugene Smith)

So this year, like every year, we want to spotlight ten debut collections and the ten lives in poetry that led to those books. We want to celebrate Anthony Cody’s inventive, visually sprawling Borderland Apocrypha and his practice of writing lines in a phone book. To celebrate Chessy Normile’s humorous, vulnerable Great Exodus, Great Wall, Great Party, and the four friends who read her manuscript and urged her to see it for what it was. To celebrate the taut and visceral poems in Tommye Blount’s Fantasia for the Man in Blue and his habit of sitting by Walled Lake near Novi, Michigan, to write. To recognize the books of the poets featured here who write while balancing multiple gigs, who write while contending with trauma, illness, and great change.

In their replies the poets offer a broad range of advice for writing through impasses and publishing a collection. Common ideas surface: Many recommend writers take their time and take ownership over their work, like Destiny O. Birdsong, who says, “Time made it better because I got better at being myself as a poet, at hearing my own voice and following my own instincts.” Several suggest focusing not on public recognition, but on sharing your book with your community and, as Claire Meuschke says, “leaning toward the select few who enjoy your work.” And threading through all the poets’ replies is a sense of how joyful and how hard writing can be. “You are doing difficult, vulnerable work,” says Leila Chatti. “Language is such a complex and unwieldy technology, capable of profound softness and unfathomable violence,” says torrin a. greathouse.

Many authors and publishers have noted that 2020 has been an unusually difficult year to release a book, especially a debut. “You’re going to face challenges beyond your control,” Roy G. Guzmán says. Public health precautions have precluded many in-person book gatherings, and many writers have likely found releasing a book to be removed from, or secondary to, the demands of caring for themselves, their families, and their communities. So in a year when it might have felt strange for anyone to draw attention to their debuts, we are glad to fete these poets a little, these authors whose books have emerged from a committed and sustained engagement with poetry.

Anthony Cody, Taylor Johnson

Leila Chatti, Destiny O. Birdsong

Chad Bennett, Claire Meuschke

torrin a. greathouse, Chessy Normile

Tommye Blount, Roy G. Guzmán

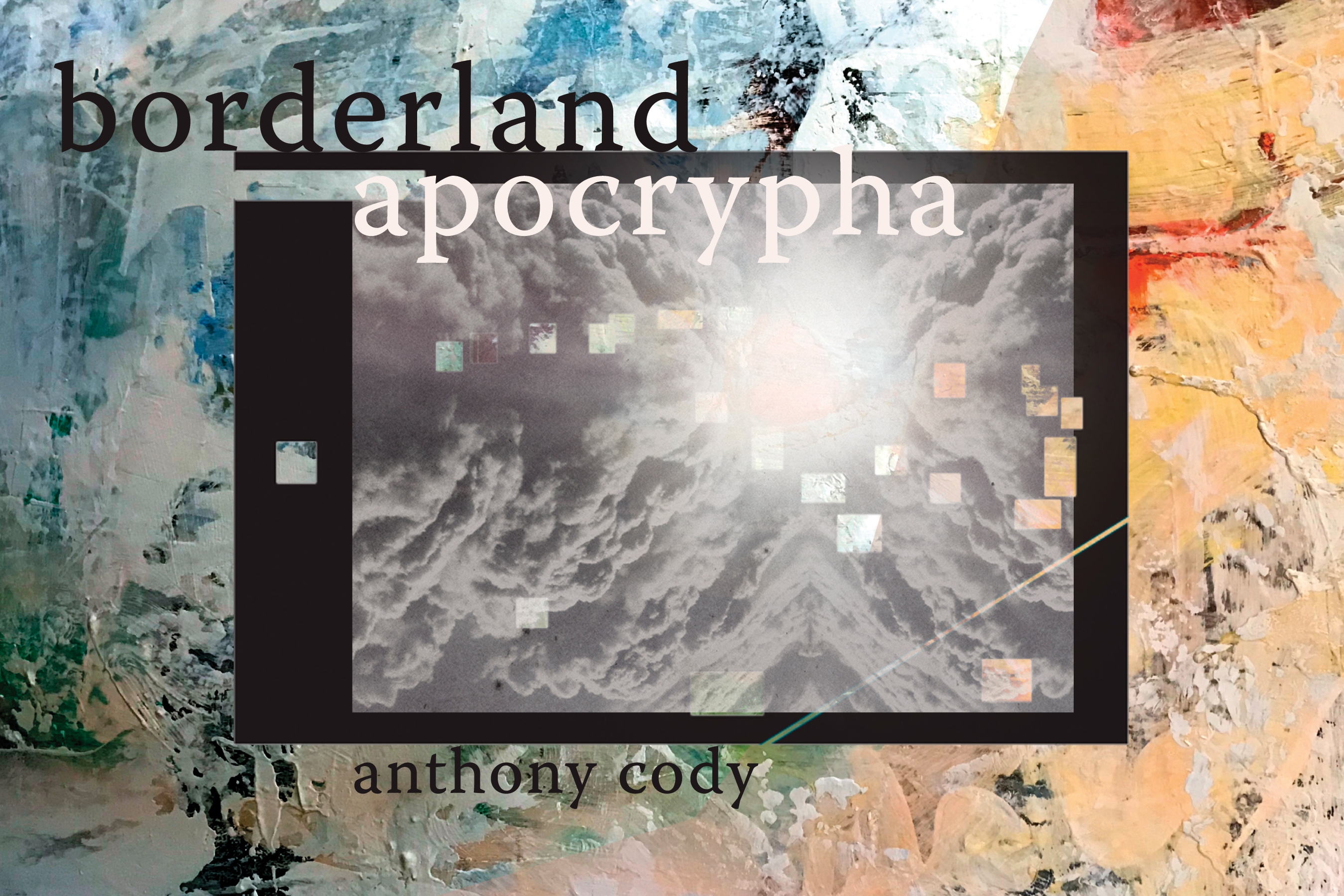

Anthony Cody

Borderland Apocrypha

Omnidawn Publishing

(Omnidawn Open Poetry Book Contest)

To narrow a body, excise.

—from “Bracero(s) & The Ice Car”

How it began: I was preparing to leave the country on a trip and had to take a passport photograph at a local drugstore. While I was in line an older white man stood uncomfortably in my personal space and made a joke—in reality a microaggression—asking me if I was afraid of the current president and trying to flee the country. Perhaps it was milliseconds, perhaps it was minutes, but in that provocation all the scenarios of what could happen next played out in my mind. Would I confront him? Would I laugh it off? Would I say anything? Ultimately I took a half step toward him and looked into his eyes without expression. He backed away and left. This moment sat with me for months, and I ended up writing a poem about the event. As time went on I began making more connections between that poem, which would become the opening poem of Borderland Apocrypha; the archival research around the period the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed; and the subtle, and not so subtle, histories that had built up to the moment.

Inspiration: Being in community with other poets, writers, and artists. The act of writing feels like a meditation in loneliness and often a study in rejection, so community feels vital. To talk, collaborate, share your work, manifest, dream, and support one another in the struggle helps keep me grounded and focused. The Hmong American Writers’ Circle, CantoMundo, El Taller Latino Americano, and the Laureate Lab Visual Wordist Studio are very specific sources of inspiration in my life. Within these communities, I have encountered others whom I have learned from and created alongside. They have nourished me, and I approach every day trying to put that cariño and energy back into the universe.

Influences: One day Juan Felipe Herrera said to me, “Abandon the left margin.” It was a new liberation to my practice and process. He is also the author of Akrilica (Alcatraz Editions, 1989), a collection that after almost three decades still reaches into the imagination of the possibilities of Latinx poetics. Even to this day, he still gathers others, dreams, and seeks. Witnessing him in action now, and throughout my life, reminds me to stay working toward honoring him as both a mentor and friend in everything I do.

To read a collection from M. NourbeSe Philip is to feel as though I am being invited into the sacred. A space I must read and enter with a care over the next several weeks. Her work re-synapses my understanding of language and navigation of the field in a way that requires me to turn off all other distractions and devote my full attention to her writing.

When I opened The Black Automaton (Fence Books, 2009), my life changed. Douglas Kearney’s ability to have a multiplicity of voices, textures, and histories—all within a visual deconstruction layered in complexity—created something that was new to me. This book made me realize I had to start over and ask more from my writing.

I return to Muriel Rukeyser’s U.S. 1 (Covici Friede, 1938) year after year. More than a primer in docupoetics, her collection delves into the experimental and grounds me with a deeper understanding of how a poem and a collection can be both a reckoning and a path toward truth.

So much of my life involves community that my list could go on and on. Bernardo Palombo, the founder of El Taller Latino Americano, has helped expand my mind. I spent nearly three years in New York City learning about language, art, music, and literature from the entirety of the Americas from Bernardo, an educator, an artist, as well as a songwriter and musician of the Nueva Canción movement. His passion to make space for others; his attention to languages, sounds, and voices; and his ability to scheme and dream against all obstacles astounds me and makes me a better person and poet.

Writer’s block remedy: I walk away. The internet, the algorithm, and capitalism want us to go as hard as we can until we are spent, only to start over again. If I can’t push a project any further, I change mediums or do something else entirely. I write inside a phone book. I break down cardboard and sketch and build. I read and read and read or dive into the internet and research or obsess over a song that I loop and dissolve into for days. Writing is often more about listening than it is about the act of writing, so if the writing ceases, I know it is time I stop what I am attempting, listen more, and reimagine the path.

Advice: Poetry is not a competition or a race. For many years I did not write regularly. I worked. I read. I wandered. For much of my twenties, and even a portion of my thirties, I engaged in a variety of creative projects all while working at nonprofits, as well as at a wastewater reclamation and recycling plant. I did everything except write poems. All those friendships, experiences, and time gave me a chance to slowly understand the book I wanted to write into this world. So feel urgency, but do not confuse that urgency with the need to rush into publishing your first book before it is at a place that you can accept.

The other piece of advice: Find yourself two or three friends, poets or not, you can text a poem to at 3 AM and who will unflinchingly tell you the truth: “Nope” or “This is good, keep grinding” or even “You’ve lost your way.” All the aforementioned replies have helped save me from myself. Without those people in my life, I am unsure what kind of book Borderland Apocrypha would have become, or if it would have even become a reality.

Finding time to write: I have learned that I cannot physically force myself to write, so setting time aside does not necessarily help me write more. Instead, I am often scribbling, sifting through the internet, listening to music, or sitting with an idea, a line, an image, or a concept. As a result, I may not be “writing” while doing a variety of other jobs and things, but I feel I am always mentally drafting and constructing in preparation to write.

Putting the book together: The second and third sections that center the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the subsequent lynchings, hate crimes, and traumas against Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the southwest United States are predominantly in chronological order. The series that begins the collection became the opening section after I realized I was writing a group of poems that created a divergence of pathways, both personal and not, related to my research. Initially I believed I was drafting two separate manuscripts. For the closing of the manuscript, I had at first titled all the poems with the ending clause “as Borderland Apocrypha.” While this maneuver did not make the final manuscript, the dissonance between the title and the subject matter of the poems did help me understand that the poems were steadily drifting from the harms of the past and present, beyond survival, and toward resistance.

What’s next: Immediately after finishing the final draft of Borderland Apocrypha, I returned to the MFA program at Fresno State—I had deferred the last two years of the program. Rather than use the book as my thesis, I made the decision to dive into my paternal grandparents’ experience in the Dust Bowl; make sculptures, both tangible and sonic; create mural-sized poems and scrolls; and assemble a new body of cross-disciplinary work that examines the Dust Bowl, climate change, complicities of whiteness, and annihilation.

I am grateful that this current work is steadily appearing in the world, and the best way I can describe the new work is as an escalation into the borderless aesthetic that I am exploring in Borderland Apocrypha.

Age: 39.

Residence: Fresno, California.

Job: I am currently shifting from my MFA in creative writing at Fresno State to looking for a full-time job. In the meantime I serve on the volunteer communications staff for CantoMundo and as an associate poetry editor for Noemi Press.

Time spent writing the book: Outside of research that began several years ago, the majority of the collection was physically written and revised over thirteen consecutive months. This was an intense period of time during which I simultaneously researched, drafted, drew, constructed, and built poems at all hours of the day and night.

Time spent finding a home for it: It was about a year between when I first thought I was finished with the manuscript but continued tightening the collection to when I heard I had won the Omnidawn Open Poetry Book Prize.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Each year poetry gives us a staggering number of debut voices. Some of the collections that left me in awe to share a debut year with include Tommye Blount’s Fantasia for the Man in Blue (Four Way Books), Monica Sok’s A Nail the Evening Hangs On (Copper Canyon Press), Alan Pelaez Lopez’s Intergalactic Travels: poems from a fugitive alien (The Operating System), Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions), Michael Torres’s An Incomplete List of Names (Beacon Press), Jihyun Yun’s Some Are Always Hungry (University of Nebraska Press), and Ricardo Maldonado’s The Life Assignment (Four Way Books).

Borderland Apocrypha by Anthony Cody

![]()

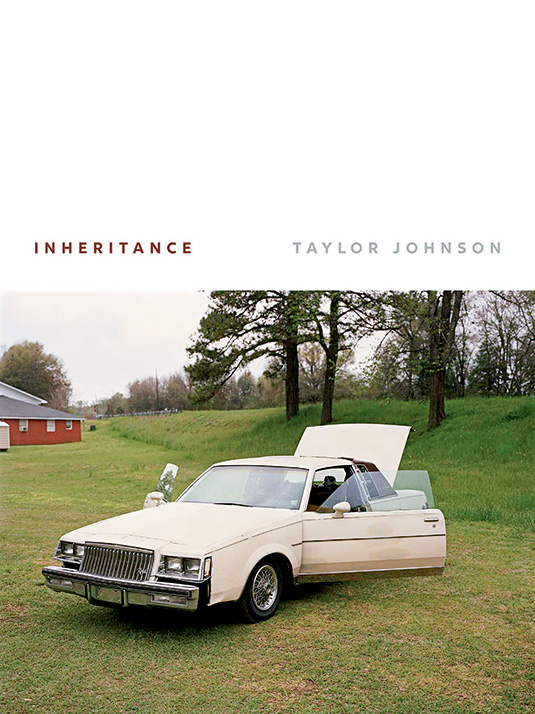

Taylor Johnson

Inheritance

Alice James Books

No name in the city of undoing

I lengthen beyond what I know

—from “self/hood”

How it began: I don’t know if I was thinking about the poems I was writing as something that would be a book. The poems in Inheritance were formed while I walked around D.C. or had conversations with friends and lovers, or as a response to a theoretical framework I was trying to understand. Each poem has its own sense of time and reality, and I wasn’t considering other poems that I’d written when I was in the process of writing a new one; I let the sounds emerge as their own. Ultimately the compulsion was to respond.

Inspiration: Riding public transportation in D.C., walking Georgia Avenue, walking Fourteenth Street, laughter, the Greyhound bus, The Poetics of Space (Presses Universitaires de France, 1958) by Gaston Bachelard, Fred Moten’s consent not to be a single being trilogy, go-go music, Roland Barthes’s essay “The Grain of the Voice.”

Influences: Christopher Gilbert’s Across the Mutual Landscape (Graywolf Press, 1984) found me in a used bookstore in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and when I read it, it seemed as if we’d always been in conversation.

When I was twenty-one I was fading out of school and I found Fred Moten’s In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (University of Minnesota Press, 2003) and his collaboration with Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Minor Compositions, 2013). Both texts changed how I understood critique, which is adoration, and study, which is connection.

I first applied to Cave Canem when I was sixteen after reading Dawn Lundy Martin’s poem “Negrotizing in Five or How to Write a Black Poem.” In the moment, the poem reached me where I was, which was inside the process of articulation and learning my own language—“phonemic struggle,” as Martin says in the poem.

Writer’s block remedy: Lately, listening to Keith Jarrett’s concert in Köln, Germany, has kept me going. I’m moved by his vocalizations and foot-stomping in the first part of the improvisation. If I’m at an impasse it means I’m stopping myself. When I stop myself it’s because I’ve reached an emotional impasse, for which I take a walk to try and work it out. Sometimes if I’m at an impasse in writing, I’ll watch a film; it’s been Cléo From 5 to 7 these days.

Advice: I think it’s important to find silence and to be periodically defamiliarized with your voice and your sense of saying things.

Finding time to write: I write everyday, usually notes that may become a poem, or some other thought that expands into maybe a drawing or an idea for something more physical.

Putting the book together: I listened to John Coltrane and his quartet playing “India” live at the Village Vanguard in 1961. I listened to the poems I had and realized that I had a series of consistent sounds throughout. At the time of putting the manuscript together, I was in Paris and would walk around the Jardin du Luxembourg saying the poems to myself and figuring out the kinetic sense that I wanted to convey with the poems.

What’s next: Right now I’m looking for two telephones booths to work out an idea I have. I’m interested in experiences with art that are immersive and require the participant to step into a new reality in some way.

Age: 29.

Residence: New Orleans.

Job: I engage my mind for a living. I write poems and have begun exploring creating installations and expanding my sense of a poem into something physical and immersive.

Time spent writing the book: Four years.

Time spent finding a home for it: I didn’t try to find a publisher. I felt that when I was ready to share the poems, there would be someone who would want to collaborate with me on that project of sharing. I took about three months to decide on whom I wanted to collaborate with.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Semiotics by Chekwube Danladi (University of Georgia Press), Horsepower by Joy Priest (University of Pittsburgh Press), and A Nail the Evening Hangs On (Copper Canyon Press) by Monica Sok.

Inheritance by Taylor Johnson