Leila Chatti

Deluge

Copper Canyon Press

...All night I listen

for you listening. If there

is something you need

to tell me, God you must

tell it to me

yourself.

—from “Annunciation”

How it began: I first became sick—or realized I was sick—in 2012, the year I applied to MFA programs. The entirety of my MFA overlapped with the illness at the center of Deluge; I would go to class, then to the hospital, and then return home to write my poems for workshop. I wrote the initial poems in Deluge not because I imagined I was writing a book, but because I was learning how to write and because I desperately wanted to understand my experience; poems were how I processed and grieved. It wasn’t until a year after my graduation, when I was living with my mentor Dorianne Laux, trying to sort out what to do next with my life, that I realized, with her insight, I had begun a book. What compelled me to finish the book were the questions writing unearthed for me and the understanding that my specific experience of misogyny—in faith, medicine, and literature—was part of a larger, urgent problem I couldn’t look away from.

Inspiration: I read a good deal of scripture and religious texts while writing the book—the Qur’an and the Bible, hymns and hadiths, as well as other spiritual texts such as Saint Hildegard of Bingen’s Scivias and Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love. I also spent a lot of time in museums looking at the religious artwork, particularly the depictions of Mary.

Influences: Sharon Olds is a major early influence on my work. Her poems emboldened me to write audaciously about the female body and sexuality. I was stunned when I came across her poems in college—I didn’t know a person could write about menstruation, desire, and the body quite that way. Her work opened a crucial door for me, and I am eternally grateful; I wouldn’t have written these poems if hers had not come first.

Louise Glück is another significant influence on my work. I first read “The Untrustworthy Speaker” as a high school student and thought, “Okay, this is poetry. I want to do this.” Glück’s Poems 1962-2012 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012) is never far from me; I keep it on my desk, and take it with me when I travel. I admire her frankness, the clarity and concision of her language, and her unflinching self-examination. I strive to scrutinize the world, starting with myself.

Margaret Atwood is a writer whose work I also first encountered as a teenager and immediately became enamored with. The Handmaid’s Tale (McClelland & Stewart, 1985) engaged with themes I had already begun grappling with as an adolescent—faith, power, and the female body. After reading it, I hunted down the rest of her work in the library and devoured it. This thorough fixation lead me to discover Atwood’s poetry, and hers were the first full-length collections of poetry I ever read. Power Politics (House of Anansi Press, 1971) blew the top of my head off.

Writer’s block remedy: Form is something that helps pull me out of wordlessness. It’s like a rope I can hold on to and inch my way forward. I love rules and restrictions—I’m sure this is a vestige of my religious childhood—and I love puzzles. Often my impasses in writing arise because I am afraid or I am bored. Puzzles cure the boredom, and rules create a scaffold that’s comforting, secure. I feel less afraid when I know I won’t open up and spill uncontrollably all over the page, that there’s a shape to contain it. I also know what’s expected of me: Rhyme here, repeat there, wrap it up in x lines or syllables.

Something along those lines, but a little more flexible, is the use of prompts. I keep word jars and lists, and will sometimes pick fifteen words at random and challenge myself to write a poem with them in fifteen minutes; I also include rules here, such as “a question must appear in the fourth line that is not answered” or “use a non-English word in an end rhyme,” because I find requirements generative. I read all the time and take notes on what I read, and flipping through these journals often sparks an idea.

Regardless of how the individual poems start, what really is essential is that I keep to a daily writing schedule. I know this doesn’t work for everyone, but I’ve found I need to maintain momentum or else writing becomes much more arduous to pick up again; I experience it as a runner might, feeling winded and exhausted if I try to run a marathon without practicing consistently. A little every day keeps me from stalling when I look at a blank page, and often I discover my best ideas not from a bolt out of the blue, but through chipping away at something long enough and consistently enough.

Advice: The first thing: Protect your heart. You are doing difficult, vulnerable work. There are many factors along this path outside of your control, but you can control how you spend your energy and how you care for yourself. My friendships with other writers have been immensely nourishing and encouraging. Surround yourself with people who truly want you to succeed, and protect your heart so you can genuinely reciprocate. Be mindful of how much time you spend online; if it’s a source of negativity and incites feelings of anxiety, insecurity, and discouragement, you’re better off spending those hours reading a book or, of course, writing. Read a lot, widely, including some books published more than five years ago. If possible, try to work on another project (or three) while sending out your manuscript—this can help distract you during the insufferable waiting period, and reduce the stress you put on this one project. Have a trusted handful of people read it, and then have faith. It can take time for the right circumstances to line up—the right readers, the right judge or editor, the right moment—but have faith that this will happen if you keep showing up for your book, keep sending it out. Keep going.

Finding time to write: Usually I write every day. I fell off of my routine for about a year, however, after my book got picked up and I became distracted with new, ever-changing responsibilities. I believed, falsely, that I needed to first take care of everything else—work and life tasks—or else I wouldn’t be able to focus on my creative work, but there was always more to be done, and so writing got less and less of my time. I wrote right before bed, on my phone, tiny snippets, but I was miserable. Finding time, I realized, was a fantasy—I have to make it. I’ve now resumed my original routine, scheduling it in and taking it as seriously as I would a teaching or speaking engagement. I write first thing in the morning, at 7:30 every morning, no matter where I am, and I write for at least two hours. Instead of hoping my writing would squeeze in somewhere, now I find time to squeeze in my other assorted tasks. Writing is my priority, so I have resolved to give it my first and best attention each day. One tip that’s helped too: I check my e-mail only when I am prepared to respond. Cutting out random checks during the day on my phone or computer drastically cut down on wasted time and added anxiety. Those extra minutes add up, and I’d rather open up a document I’ve been working on and fiddle with that when bored or antsy.

Putting the book together: I’m hyper-organized and obsessive, so I created a fairly complicated system of charts to track various aspects of the book and to have a clear overview of its threads, how things were balanced, and where I might need to write more poems. I also printed the poems very tiny and glued them onto notecards; on the other side of the card I had a system of symbols and colors representing themes and formal or structural elements in the poem. I scattered these across my living room floor and then moved them around, making connections through the randomness I might not have otherwise. I then kept these in a plastic bag and flipped through them during my commute, reading through them and tweaking the order.

I also spoke with Gregory Pardlo about how to order a manuscript, and he gave me a great bit of insight. He said the “reveal” of the book, its dramatic climax, is not that I survive—that’s obvious, because I lived to write the poems. So, he pushed me to consider what understanding or revelation was the book working toward? This helped me to think outside of “sick then better, the end” as the book’s arc and chronological fidelity as the sole ordering principal. Breaking the book into sections—the version it exists as now—happened about six months after I finished the first draft; I realized the book felt very heavy uninterrupted, and I wanted to add in some space for breath. This also helped me to escape some of the constraints of linearity.

What’s next: I’m currently working on a project that I began this fall for a manuscript workshop for my PhD. The poems are all in form; I’m coming off of a long silence—the pandemic knocked language out of me, and before that, I was preoccupied with pre-publication work on and for Deluge—and the challenge of form is generative for me, keeps me pushing into the unknown. This project is much more playful than Deluge, which I think is good for me. My father always says, “Everything in moderation.” I find comfort in balance. Deluge is very serious, and I was very serious while writing it. Now I’ve wandered in another direction, playing games with language and ideas, loosening my grip, letting in some surprise and wildness. Unlike Deluge, for which I had very clear vision and aspirations, I don’t know what I’ll do with this project; at the moment I’m just having fun.

Age: 30.

Residence: Cincinnati.

Job: I am currently pursuing my PhD in creative writing at the University of Cincinnati. I also teach online writing workshops, which I love.

Time spent writing the book: The oldest poem in the book—“14, Sunday School, 3 Days Late”—was written in 2013. The last poem added to the manuscript, “Haemorrhoissa’s Menarche,” was written in 2018; I think of the book as having been finished in late 2017, but I wrote this teensy poem in a workshop led by Alicia Suskin Ostriker as a challenge to write a poem in under a minute. So, five years, technically, though the vast majority of the writing was concentrated between 2015 and 2017, during a heightened burst of creativity and production when I also wrote my chapbooks Tunsiya/Amrikiya (Bull City Press, 2018) and Ebb (Akashic Books/African Poetry Book Fund, 2018).

Time spent finding a home for it: About a year. I was very cautious about sending the book out for a whole range of reasons, many of them silly. I first sent it to a few contests in the fall of 2017. I mustered the courage to submit my manuscript to Copper Canyon’s open call the following summer, as well as to another press whose editor invited me to send it their way. I was even more timid about sending my book to these presses because a no from a press felt absolute; I could always re-enter a contest, but if a press rejected the book, I figured (perhaps erroneously), that was that. That fall was silent and nerve-wracking. I finally broke one night and wrote my mentors these painfully despairing e-mails asking how to keep heart and expressing my doubt and dejection (to which they responded kindly, with encouragement, compassion, and stories of their own). I stayed up all night after this outpouring working on an impromptu research project tracing the lives of women writers I admired, mapping them out on timelines—education, books, prizes and other markers of achievement, marriages and children—to see if there was a pattern, and was relieved to see there was not, that there was a multitude of paths. This discovery filled me with great calm. The next day, January 14, 2019, I received the phone call from Michael Wiegers saying Copper Canyon wanted to publish the book.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: I loved Philip Matthews’s Witch (Alice James Books), Jessica Abughattas’s Strip (University of Arkansas Press), Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions), and Jameson Fitzpatrick’s Pricks in the Tapestry (Birds, LLC). I’ve moved a number of times this wild year, so I’m still waiting to get my hands on books I had sent to different addresses—Marianne Chan’s All Heathens (Sarabande Books), Sumita Chakraborty’s Arrow (Alice James Books), and Allison Adair’s The Clearing (Milkweed Editions) are among them, and I can’t wait to read them!

Deluge by Leila Chatti

![]()

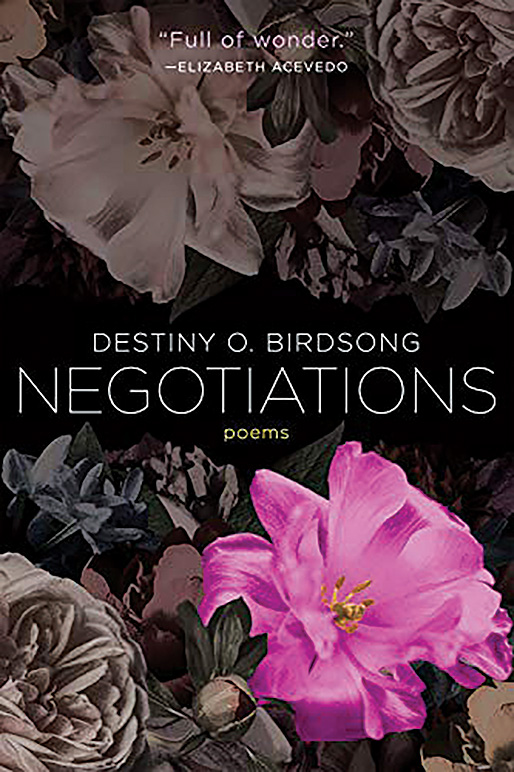

Destiny O. Birdsong

Negotiations

Tin House

This is a singular, decadent life, a truth

I know would kill her,

or make her murderous in its knowing.

—from “Her”

How it began: It was a few things. Rage at a hate crime I experienced in 2016. The fear that if I didn’t write it right then, I’d never finish a book that was good enough to publish. Sorting through trauma. Wanting to tell a very particular truth I wasn’t seeing in the world. A real sense that writing was the one thing I was supposed to be doing and the suffocating realization that I was wasting my life by not doing it because I was afraid of the work I knew it was going to take.

Inspiration: When I first watched Beyoncé’s Lemonade I was…uncomfortable, and it wasn’t because of the content. As an artist I could tell that Beyoncé had taken inventory of an already-fruitful career and said to herself, “I can do more. I have more to give.” I could tell that she had broken through her own ceiling, and the gifts we got from that breakthrough are incredible: Lemonade, Black Is King, and my favorite, Coachella and its Homecoming documentary. When I watched Lemonade in 2016, I felt called out because I wasn’t even close to a “breakthrough” moment—I was barely writing at all. But three years later, after struggling to write my book through all kinds of emotional crises and health scares, I watched Homecoming and I felt like my struggles made sense. Beyoncé’s journey toward doing something that had never been done before—being a Black woman headliner for Coachella—gave me context for my own, and she sets a bar of excellence that I strive to meet every day. I’m nowhere close yet, but she gives me something to reach for.

Influences: Natasha Trethewey: In graduate school, one of my professors looked at me in disbelief and said, “You’ve never heard of Natasha Trethewey? You need to read Natasha Trethewey,” and when I did, I understood his disbelief. When I think of my calling as a Southern writer, as a Black woman Southern writer, and as a Black woman Southern writer who writes about familial trauma, I think of Trethewey and the contemporary path she paved for folks like me. And when I think of books whose level of perfection I aspire to, I think of Native Guard (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), and how much she accomplished in such a small space: the interweaving of public and private histories, the use of form in service to narrative (and not as a mere stylistic flourish), and the beauty of brevity (which I’m still learning to do). Her work sets a bar—a distinctively Black, Southern, and woman bar. This is important because as rich as the legacy of Southern literature is, it’s also flawed. Some of our geniuses were virulently racist. I can go to Trethewey’s work to savor and learn without having to worry about being lampooned, tokenized, or insulted for being Black when I turn the page.

Lucille Clifton: There are meals that remind me of home—beef tips, cornbread dressing, pancakes with jelly—that are rich in flavor and memory, and that fill me up and sustain me both nutritionally and otherwise. Clifton’s work does that every time I return to it. But there’s a deceptive quality to the plainspokenness of her lines that people often miss. It reminds me of how, now, every gentrified city in the country is overrun with soul food restaurants, not only because the food is good, but also because its flavors are complex, its variations are astounding. That’s what Clifton’s work does for me: I can settle into it, but I always find some new note of flavor I hadn’t tasted before. I try to create work that does that.

Edwidge Danticat: I picked up Breath, Eyes, Memory (Soho Press, 1994) when I was eighteen, and it was the first book I ever read that spoke directly to the complicated but loving relationship I have with my mother; it gave me permission to write openly about it, which I would ultimately do nearly a decade later in my MFA thesis. But the other gift Danticat gave me happened when she visited the Nashville Public Library in 2013 to promote Claire of the Sea Light (Knopf, 2013). During the reading, she said that some of the best advice she ever received was, “When you have a book coming out, start another one.” That way, no matter what that forthcoming book’s reception is, it won’t stop you from writing, and you’ll have something to look forward to. With that advice, Danticat taught me how to write consistently, even when no one is looking for my work. My next book was drafted that way, and it was a luxurious experience. I got to spend as much time as I wanted with it because no one was expecting it, and no one’s opinion was there to shape what I wrote. I also didn’t feel any external (or egotistical) pressure to get it done because Negotiations was already under contract. So I set my own deadlines. It was awesome.

Dolly Parton: I once watched a biography of Dolly Parton, and learned that, in the 1970s, Elvis Presley wanted to record a version of “I Will Always Love You.” The problem was that, according to Presley, he only recorded songs he owned the rights to, and Parton never sold the rights to her songs. So the deal fell through, and at the time it probably seemed like a huge missed opportunity. But fast forward a couple of decades: Whitney Houston records the same song for The Bodyguard, and Dolly Parton boasts that she made enough money from that recording to buy Graceland. I think the influence here is more about protecting the work than about the work itself (and “the work,” can mean anything—from your written words to how you want them represented): Stick to your principles. If you really believe you should retain ownership of something that’s yours, fight to keep it. Some stuff should never be for sale, no matter who’s asking. And finally, time will always reveal the full value of a good decision.

The other thing I admire about Parton is her Imagination Library, which provides free books for kids from birth until they begin school. It’s an initiative she credits in part to her father’s illiteracy. What a way to live as an artist—giving back not only because you can, but because you deeply understand lack of access, so you give out of the memory of a familial wound. I aspire to that, and it may be the most important work I could ever do.

Writer’s block remedy: Music. Talking shit and dreaming with my friends. Naps. Organizing my space. Walks. Recording voice notes of myself hashing out ideas. Outlines. Reading pieces outside the genre I’m working in.

Advice: Time is your friend, and timing is divine. In the words of Ada Limón, I wrote the best damn book I could. But if I’d published it ten, five, or even two years ago, that wouldn’t have been true. Time made it better because I got better at being myself as a poet, at hearing my own voice and following my own instincts. That’s a process you can’t rush. Also, every single time I’ve tried to rush something, it’s done me more harm than good, and set me back farther than I would have been had I left well enough alone. I’ve learned to take opportunities when they arise, but to place the bulk of my focus and energy on preparation. I had a friend who used to say, “If you stay ready, you ain’t got to get ready.” I believe that. Being ready for the thing that’s coming is a way better use of my time than trying to hurry the thing up.

Finding time to write: Theoretically, I should have the whole day, but it doesn’t always turn out that way, and I don’t believe in spending more than four hours a day writing unless there is some huge inspiration or looming deadline that won’t let me go. During the pandemic my friend Claire and I started hopping on Zoom together for an hour or so to write on weekdays, usually in the afternoons. I also sometimes have trouble going to bed at a reasonable hour, and if I can’t fall asleep, I get up to write.

Putting the book together: It happened in two parts: There was the order of the manuscript that got picked up, and the order of the one that got published. When I was ready to send it out I did the traditional thing and spread the pages out on the floor and grouped poems in sections by general theme: sociopolitical poems, poems about illness, poems about sexual violence, and poems about solidarity and joy. After the book got picked up, I had a conversation with my editor, Matthew Dickman, who (very gently) said two important things: 1) The first section was a little disjointed, and 2) you don’t have to try to squeeze everything into three or four sections. And it was like a light bulb came on. I went back to the floor, but this time I let the poems fall into as many sections as they wanted, even though I kept the general thematic order of the outlines above. Some poems left. Some poems were added, and two were written. When I was done, there were six sections, including the title-poem section that opens the book.

What’s next: I recently sold a triptych novel about three women with albinism who live in my hometown of Shreveport, Louisiana, and I’m currently working on a few revisions for that. Also essays! I’ve been writing essays and thinking toward a collection.

Age: 38.

Residence: Nashville.

Job: I write full-time for now, which sounds deliberate, but it isn’t. I lost my job at the end of 2019 and couldn’t find another one, so I said, “Welp, I guess I’ll try this thing out and see what happens.” It’s been good, but I do things to supplement my income, like freelance editing and facilitating community workshops.

Time spent writing the book: Some people say their first book or album took their whole lives to write, and that feels somewhat true for me, but I began writing it in earnest in 2017. Some of the oldest poems date back to 2015.

Time spent finding a home for it: I’ve sent manuscripts out for years, but I started submitting what would become Negotiations in late November 2018. It was picked up the following July.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Aricka Foreman’s Salt Body Shimmer (YesYesBooks) and Monica Sok’s A Nail the Evening Hangs On (Copper Canyon Press).

Negotiations by Destiny O. Birdsong