This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Saeed Jones, whose memoir, How We Fight For Our Lives, is out today from Simon & Schuster. Raised in Texas, Jones begins his story in Lewisville, Texas, where as a twelve-year-old boy he discovered his mother’s copy of James Baldwin’s Another Country. “Holding Another Country in my hands, I felt that the book was actually holding me,” he writes. “Sad, sexy, and reeking of jazz, the story had its arm around my waist.” Tracing his journey of finding and fighting for a life of his own—from Lewisville to Memphis and across the Atlantic and back again—Jones describes necessary distances and cleavings, but also pays tribute to home and particularly the love and labor of his single mother, who died in 2011. “Both love song and battle cry,” writes Jacqueline Woodson of the memoir. “Brilliant as fuck and, at times, heartbreaking as hell.” Saeed Jones is also the author of a poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise, winner of the 2015 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award and a Lambda Literary Award. A graduate of Kentucky University and Rutgers University in Newark, Jones currently lives in Columbus, Ohio.

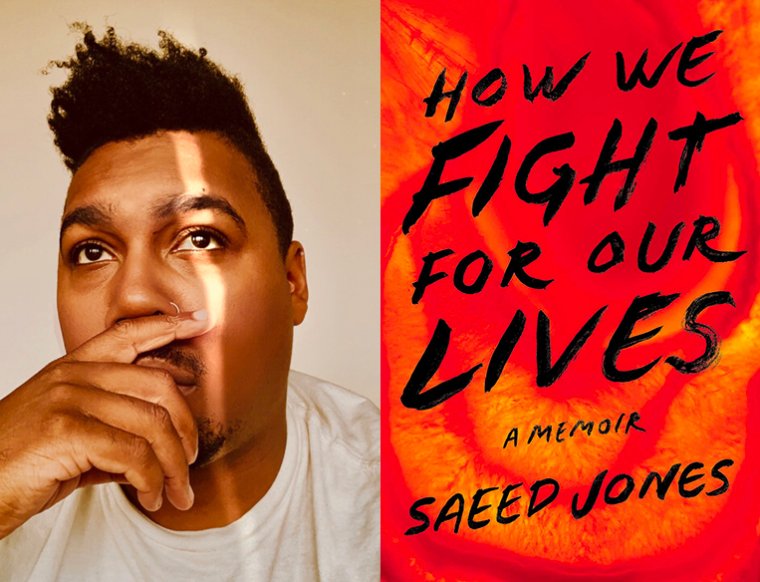

Saeed Jones, author of How We Fight For Our Lives.

1. How long did it take you to write How We Fight for Our Lives?

The earliest iteration of the book was an essay about the most beautiful man I’ve ever kissed trying to kill me. I started writing it a few days after it happened in January 2008. I wrote what eventually became the first chapter of the book when I was in graduate school. I think I always knew this book was coming, one way or another. I started writing in earnest in 2011, sold the book on proposal in 2015, and finally finished it at some point last year. Now I find myself in the bizarre position of having to figure out who I am without this book’s writing process being a part of my daily life.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Because the book is about me, whenever I was struggling with a part of the book I’d begin to wonder if I was struggling because I don’t really know who I am. I thought that surely, if I knew who I was, writing about myself would’ve been easier. It was a vicious loop and very depressing. The process of writing a memoir can swallow you whole if you aren’t careful. I started therapy in 2017, which helped tremendously. I thank my therapist in the Acknowledgements for that reason.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When I’m home in Columbus, I wake up around 8:00 AM, listen to a podcast while I drink coffee, and then write until I’m hungry around 11:00 AM or noon. I probably write five or six days a week. My desk is up against the window; there is a lot of light, which is important to me, and good views of shirtless men jogging up and down the street, which is also important to me.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino. I keep highlighting every other paragraph and then reading what I’ve highlighted out loud. Experiencing her work with my eyes just isn’t enough; I want to hear it too. And this morning, I plucked Michael Lee’s chapbook Secondly, Finally from my shelf. The first poem is so good, it made me mad. Like, how dare you? That’s my version of a starred review. I’m excited to read his new book, The Only Worlds We Know.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I will not rest until every person in America has read The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. She’s hardly an unknown writer, and that book, rightfully, has received a great deal of praise. But look at what’s going on in our country. Clearly every American hasn’t read it yet, which frankly is traitorous.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I think it’s essential that we get more comfortable talking about money, contracts, and the business that enables our art to reach readers wherever they might be. The idea that it’s rude to talk candidly about book deals and contract negotiations serves the publishers very well but endangers writers, especially emerging writers. A healthy discourse about money would expose just how much publishing depends on the scam of white privilege, which is why gatekeepers work so hard to delay and derail the conversation.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Honestly, what sticks with me the most is what my editor and agent didn’t say. They never said “Where is that damn book?!” or “Why is it taking so long?” My editor only gave me concrete deadlines when I would ask for them. They protected me and allowed me to do what I needed to do. I was so anxious about finishing the book but I couldn’t rush the process. A quickly written memoir is a memoir full of lies. At one point, I was at a literary gala and someone at my table made a joke—“Oh, so you’re the writer who is taking so long.” I cried when I got home that night. And even now I picture his face every time I’m within striking range of a punching bag.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

White people.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My editor Jon Cox is, simply put, the most intelligent reader I’ve ever had the privilege of working with closely. I always marvel at the insight in his notes. He’s also incredibly handsome and nice. It’s very overwhelming. Anyway, I trust him with my writing almost as much as I trust myself.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Rigoberto González helped me understand that my success as a writer would hinge on my success as a reader. I’ve translated that advice into a ratio. For every poem or page I write, I try to read three times as much work by other people. I don’t have a ledger or anything but you get the idea.