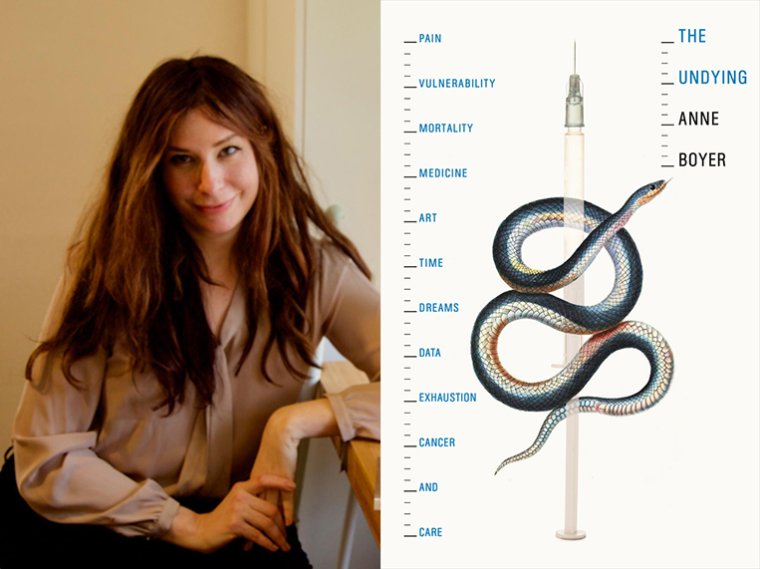

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Anne Boyer, whose memoir, The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In incisive prose, Boyer documents the diagnosis and treatment of her highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer and critiques how “the ideological regime of cancer”—as much as the malignant cells—determines the experience of illness. In the face of overtreatment, pharmaceutical greed, and the expectation of survivor heroism, Boyer turns to the long lineage of women writers examining illness with intellect and vulnerability for company: Kathy Acker, Eve Sedgwick, and Audre Lorde, to name a few. Boyer also articulates the possibilities for care in friendship—the present-day relationships that carried her through an otherwise compromised and corrupted social world. “Anne Boyer’s radically unsentimental account of cancer and the ‘carcinogenosphere’ obliterates cliché,” writes Ben Lerner. “By demonstrating how her utterly specific experience is also irreducibly social, she opens up new spaces for thinking and feeling together.” Anne Boyer is the recipient of a 2018 Whiting Award for poetry and nonfiction. She is the author of the essay collection A Handbook of Disappointed Fate and several poetry collections, including Garments Against Women, winner of the 2016 CLMP Firecracker Award. She was born and raised in Kansas and currently teaches creative writing at the Kansas City Art Institute.

Anne Boyer, author of The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care.

1. How long did it take you to write The Undying?

The Undying took around four and a half years from first word to last edit.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Cancer was, including the devastating effects of its treatment, its disabling aftermath, and its crushing ideological and social weight, felt both individually and collectively. The diminishment of life under our present conditions makes cancer—around which all the other ordinary problems of life gather and heighten—almost too much to bear thinking about without collapsing in sadness or rage. It would have been easier to survive and turn away and try to forget. I had lost my strength and much of my capacity to think when I needed both the most, and I had to learn the humility of writing a difficult book while often weak, upset, and confused. But I had made a bargain with myself that if I lived, I would give a book of what I learned back to the world in return—an act of gratitude and sometimes vengeance—and I made it through.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When everything is going okay, I like to write every morning on my sofa until around lunchtime, but in times when things are more stressful and erratic, I write whenever I can steal the time away from my paid work and my obligations to the people around me. When things are at their best and there are few demands on my time, I write from morning to night, and being able to write like that is my perfect day.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

I marvel at all the production and post-production work, the teams of brilliant and devoted people required, not just the editors and agents and publicists, but everyone else, paid and unpaid: reviewers, booksellers, assistants, teachers, interns, event organizers, designers, warehouse workers, librarians, and the people who do the infrastructural and maintenance work of all the places devoted to literature, the people who deliver books, maintain databases, clean rooms, and the people who care for all the people doing all of the above. It comes together in a way that foregrounds the name of the writer, but every book on the shelf is there because of all of these efforts, and the efforts of everyone around the writer, too, and all the other writers and the people who helped them who came before, and the people involved with the social movements and struggles that made it possible for so many of us to write and publish. A single name on a book is a ruthless abridgement of the facts.

5. What are you reading right now?

Edith Grossman’s translation of Don Quixote, which is the perfect novel of middle age.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Bhanu Kapil, Lisa Robertson, Verity Spott, Ryan Eckes, Precious Okoyomon, Joshua Jennifer Espinoza, Wendy Trevino, Jackie Wang, Nat Raha, Diana Hamilton, and Nikki Wallschlaeger are all poets or poetry-allied writers making fantastic work right now. As far as nonfiction, I am eager to read a book by Chloe Watlington. Her recent piece in Commune Magazine was astonishing.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Both of them have told me this in so many ways, which is why I work with them: Write what you need to and don’t worry about it being strange.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Capitalism, which continues to devour the living world that we need as our home and to consume the hours of everyone’s lives for the profit of the very few, setting people against each other for the mere preservation of life and pressurizing gendered and racialized forms of oppression. There’s no writing without time, without air to breathe and potable water, without a body and earth that supports life, without each other.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Capitalism.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Clement of Alexandria: “To write all things in a book is to put a sword in the hands of a child.”