This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Oliver Baez Bendorf, whose second poetry collection, Advantages of Being Evergreen, is published today by Cleveland State University Poetry Center. A vessel of both memories and dreams, Advantages of Being Evergreen documents and mends fractured relationships—between humans, between humans and nature—amid political and climate crises. “These are poems that never shy from the shocking violence and cruelty of the world,” writes Gabrielle Calvocoressi. “I don’t know when I’ve read a book that is so gentle and ferocious at the same time.” Oliver Baez Bendorf is the author of a previous poetry collection, The Spectral Wilderness, which Mark Doty selected for the 2013 Stan and Tom Wick Poetry Prize at Kent State University Press. His poems have also appeared in American Poetry Review, Poetry, BOMB, and the anthology Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics. Bendorf is currently an assistant professor of poetry at Kalamazoo College in Michigan.

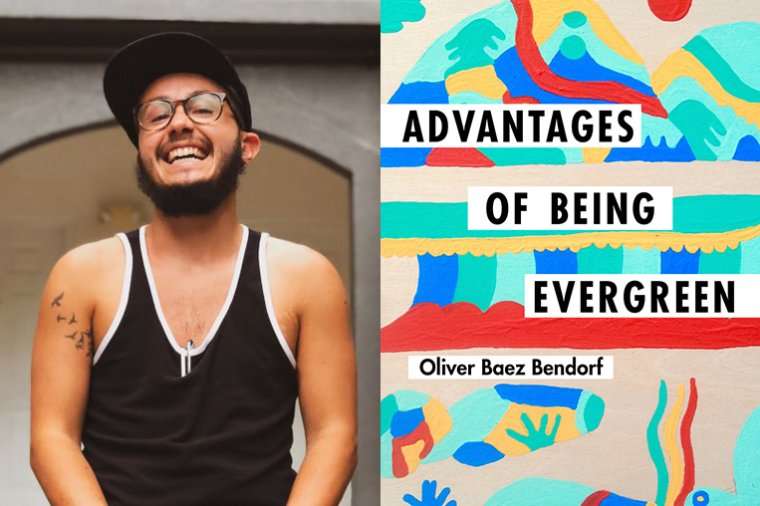

Oliver Baez Bendorf, author of Advantages of Being Evergreen. (Credit: Faylita Hicks)

1. How long did it take you to write Advantages of Being Evergreen?

I’d say my whole life. Another way of putting it is that I sat down and wrote the poems over a three-year period. Then I revised my butt off during my fellowship year at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing (2017–2018). I’m grateful for that time, which made so much possible.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Nearly everything about writing a book is hard. The hope is that it’s harder, in some way, not to. But revision and letting go were the most challenging parts for me. I kept dragging my feet during the final round of line edits because I knew that once they were done the book would be out of my hands. Once I printed out the manuscript, though, and leaned into those “final moments” with each poem, that stage of the process became a blessing, and it felt good. I was also really grateful to have supportive and smart editorial help from my press, Cleveland State University Poetry Center. It seems to me that the interval between letting go of a manuscript and having a book “forthcoming” can invite all kinds of gremlins. All the fears, doing their dance.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in a composition notebook as often as I can. I also have a typewriter, which is useful for moving things from my notebook onto a typewritten page without the endless distractions of the internet. These days, every Sunday by noon, I owe one hundred words to my e-mail writing group. Usually I write those at my desk in Michigan, looking out into the backyard, but I write them wherever I am on Sunday mornings. A few weeks ago I wrote them from my friend Alex’s house in Charlotte, North Carolina.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

That I could love the way the book looks and feels so much. I wanted a really beautiful tangible object for these poems and I’m so happy that I got it.

5. What are you reading right now?

Too much news. I like to stay informed but there’s a saturation point where I have to back away. I read a bunch of books at the beginning of the summer, and wrote about some of them for Tarpaulin Sky. The new critical edition of The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions from Nightboat Books is incredible and life-giving. I’m starting to work my way through a stack of things for some updates to my fall syllabus. And I’ve been diving back into historical accounts and records of the Community of True Inspiration, which became the Amana Colonies in Iowa. My ancestors on my father’s side were part of that community and it’s been amazing to learn more about the history as an adult.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Rane Arroyo, 1954–2010. I only came to his work a few years ago myself, so I’ve been working to spread the word. He was a gay Puerto Rican poet and playwright who was raised in Chicago and lived and taught in Toledo for many years. His voice is so present, generous, warm, and full of joy even when incisive and unbearably sad. That’s such a queer combination to me—how wonder and play continue after loss. A lot of his work is in conversation with Emily Dickinson and Pablo Neruda, through direct address. Also, the preface he wrote to his The Buried Sea: New and Selected (2008) is one of the best writers’ statements I’ve ever read.

7. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I have a handful of close friends and mentors whose ways of looking at my work teach me how to see it more clearly for myself. Some of those people are poets but not all are.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

E-mail and fear of failure.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I keep thinking there must be a better way to do Q&As after readings. Q&As sometimes feel like being back in grade school ducking dodgeballs. So many writers I know, and I’ll say that marginalized writers seem to bear the brunt of this, field oddball and careless comments and questions during Q&As. Often these seem to come from a belief that someone is entitled to more: more trauma, more background, more details, more emotional labor, just more. But to give a good reading, a writer has already given a lot. And these kinds of questions take without necessarily acknowledging what’s already been given. I think many would agree that it’d be absurd to expect a musician to do a Q&A after a live show, yet the Q&A after an author reading remains ubiquitous. Giving a good reading is hard work and it’s the live show. If people want more from a particular writer, I hope they will turn to the words that are on the page, to what’s been written: buy their book, then buy their other books. Read their work online; read interviews they’ve given. If someone wants to buy a book and ask a question as the writer signs it, that seems like a fair exchange, if they are respectful. I’m happy to talk about my work on my own terms, like in this interview, or when I’m visiting a class where students have read my work and prepared for a great conversation. If Q&As must continue, here are some ideas. For starters, never surprise writers with a Q&A after a reading—always ask in advance. They’re not neutral, innocuous, or easy for all. I recently read some other ideas that I thought were great as far as reforming the Q&A. The first: to take a very short break after the reading ends and before the Q&A starts, so that people don’t ask questions just to release steam or break the silence. Another was to have people write down the question they plan to ask, and turn to the person next to them to ask for feedback on whether the question is decent and respectful. That might sound ridiculous, but a little peer review goes a long way. I personally don’t mind the notorious “question that is actually a comment,” because it gives a break from having my brain picked, which is a grotesque image and also how it often feels. I love giving readings and I love meeting readers. So how can we have the most humane connections and treat each other with care?

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

So much of the writing advice that’s changed things for me came from my teacher, Lynda Barry. Here’s one: “Don’t forget to start it all by writing by hand. Your hand! It’s right there!”