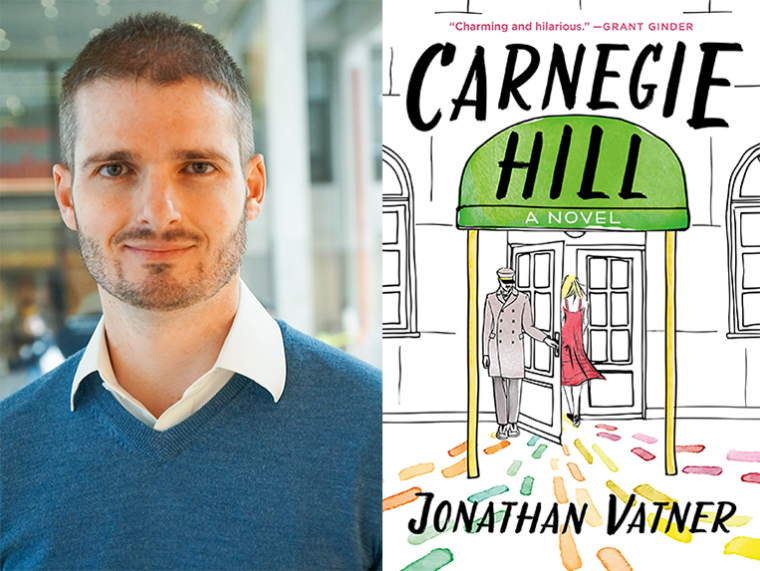

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jonathan Vatner, whose debut novel, Carnegie Hill, is out today from Thomas Dunne Books. Ushering the reader inside the world of New York City’s wealthy elite—the upper-crust denizens of Carnegie Hill, to be exact, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan—Vatner constructs a narrative web of deception and secrecy through which Penelope “Pepper” Bradford, who is having second thoughts about her financier fiancé, is forced to navigate. “You won’t envy these people for a second but you’ll have a great time watching them undo and fix themselves,” writes Joan Silber. Jonathan Vatner is an award-winning journalist who has written for The New York Times; O, The Oprah Magazine; Poets & Writers Magazine; and many other publications. He has an MFA in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College and a BA in cognitive neuroscience from Harvard University. He lives in Yonkers, New York, with his husband and cats.

Jonathan Vatner, author of the novel Carnegie Hill. (Credit: Smiljana Peros)

1. How long did it take you to write Carnegie Hill?

I started writing it in the summer of 2013 as linked stories that all took place in the same apartment building on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. I finished a draft in January of 2015. Some of my readers told me it wasn’t working either as short stories or as a novel, so I spent another year making it more novel-like, stretching a few plots throughout the book. I signed with my agent in early 2016, and we had trouble selling it—true agony!—so before he sent it out again, I spent another eight months reworking it. We sold the book in early 2017, and I spent another year revising it with my editors at St. Martin’s. I think I finally stopped tinkering with it in September of 2018. So, five years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I struggled a lot with character likability. I’ve long bristled at this demand placed on writers: It’s not enough to make characters lifelike; readers have to like them too! The truth is, though, I’ve put down plenty of books because I hated the characters so much I stopped caring what happened to them.

In Carnegie Hill, a lot of characters were acting out and didn’t know why—their blindness turned off readers. I worked really hard at not softening the most shocking scenes but instead preparing the reader with backstory and context. And then placing those characters in situations where they could be their best selves.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I wrote most of Carnegie Hill in two places: after hours at my job, and on weekends on my couch. Maybe six or seven times I carved out a week for a residency, either something I applied to or a friend’s house or a little vacation with my writing group.

Last year, however, I moved to Yonkers from New York City, and I ride a commuter train forty minutes each way to work. That’s when I write. Having to come to the page twice a day for short bursts gets me writing very fast; there’s very little wasted time. I’ve never been so productive in my life.

4. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

A legion of readers shaped Carnegie Hill in important ways…it’s very humbling to accept that I could not have written this book on my own. Of everyone who read it, I think I trusted my husband’s feedback more than anyone else’s. He’s very psychologically attuned, and he understood what I was trying to do, so I took his advice on how to get there. Another reader I trust in a different way is my friend Phil, who is also not a professional writer and who always reads my chapters first from a place of pure appreciation. Knowing that the work has value from the outset helps me weather the criticisms that inevitably follow.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m halfway through a bunch of books. On audio I’m listening to Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips, which is such a sophisticated and complex novel I can’t believe it’s her first—and I can feel the gut punch waiting for me at the end. I’m loving Very Nice by Marcy Dermansky—it’s like eating candy that happens to satisfy all your nutritional needs. On my nightstand I have two excellent books of poems by LGBTQ poets, Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith and High Ground Coward by Alicia Mountain. And on a completely different note, I’m reading an advance copy of my friend Christy Harrison’s Anti-Diet—it makes you realize just how pervasive and unnecessary dieting is. When it comes out in December, I think it’s going to change the national conversation about diet culture.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

At AWP a few years back I picked up a pocket-size book, published by A Strange Object, called Misadventure by Nicholas Grider. It’s a collection of intricately crafted and mysterious short stories about bondage. I found the craft of those stories and their subject matter deeply compelling, and I think about them all the time.

Also: A truly legendary professor at Sarah Lawrence, David Hollander, published a novel straight out of grad school and, because it didn’t sell through the advance, he had trouble finding another publisher willing to take a risk on him. And his writing is virtuosic and funny and surprising, like a David Foster Wallace or a Stanley Elkin. Almost twenty years later, his second novel, Anthropica, is coming out next spring from a new imprint called Dead Rabbits. I am mightily looking forward to it.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

The thing that seems scariest to me is the likelihood that if you’re with a major publisher and you don’t have success right out of the gate, you won’t get another book deal. I recognize that there are lots of fantastic independent presses—and self-publishing, to boot—but the financial prospects of those routes are generally unsustainable. Not only does the specter of commercial failure keep me up at night, the idea that one book could end a career implies that all of an author’s output over an entire career is basically interchangeable, that an author is what people buy, rather than a book.

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I was thrilled with the program at Sarah Lawrence College from beginning to end. It helped me take myself seriously as a novelist and an artist, it connected me with other serious writers who are publishing great work, and it sparked a growth trajectory in my craft that has continued to this day. It also greased the wheels of the publishing process: My fellow alumna, novelist Christine Reilly, recommended me to her agent, and my professors wrote bighearted blurbs to help promote my novel.

One reason the MFA was the right choice for me, I think, was that I was eight years out of college, and I’d had time to: A) get some life experience, and B) crave school again. I wouldn’t recommend the MFA to people who don’t know for sure that they want to be writers; there were some of these people in my program, and I watched them struggle. I think one would get more insight into questions of career by working in a few different industries.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Having to make a living! But I also think that if I didn’t have a job—at least a few days a week—I wouldn’t know how to fill my days, and I’d be depressed.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It came from my thesis advisor at Sarah Lawrence, Brian Morton: Don’t be subtle. After hearing that advice, I began noticing that even in classic literature, authors make their points explicitly, again and again. Obviously there are times when subtlety is called for, and readers usually appreciate the challenge of connecting a few dots. But for the most part, I’ve found success by telling readers what I want them to know.