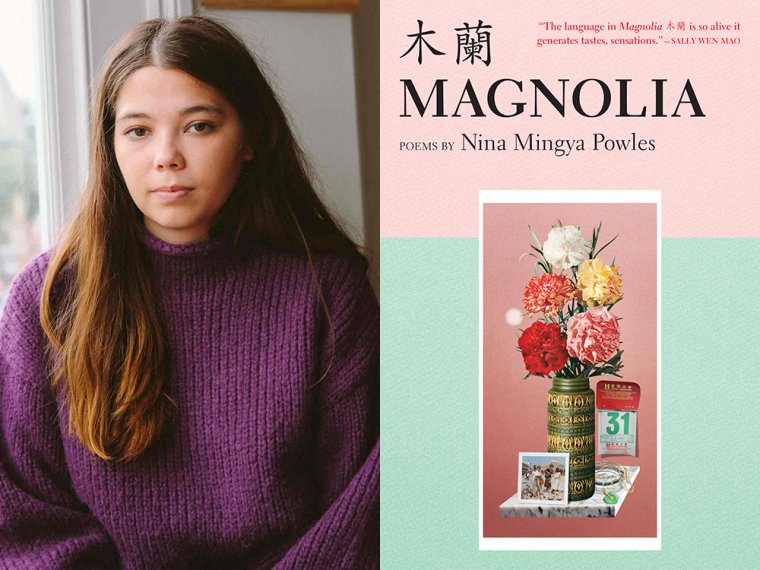

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Nina Mingya Powles, whose poetry collection Magnolia 木蘭 is out today from Tin House. In these evocative lyrics and prose poems, Powles travels among cities in China, New Zealand, and the United States, charting the topographies of exterior and interior landscapes. The collection is rooted in the speaker’s time living in Shanghai, where she savors the tastes, sights, and sounds of a city that feels both foreign and familiar to the New Zealand-born speaker of Chinese-Malaysian descent. The poems interrogate the nature of communication, from the difficulty of learning a new language to the inexpressible feelings that connect loved ones to the way the repeated images and narratives of popular culture form identity. The Disney film Mulan becomes a case in point, as the first movie the speaker watched with a “Chinese character in it” but which also transmitted troubling ideas about the female body, race, and romantic love. Publishers Weekly writes that Magnolia 木蘭 “powerfully juxtaposes moments of social commentary with insights about language.” Nina Mingya Powles is the author of several poetry zines and chapbooks, and her debut collection of essays, Small Bodies of Water, was published in the United Kingdom by Canongate in 2021. Originally from Wellington, New Zealand, Powles currently lives in London.

Nina Mingya Powles, author of Magnolia 木蘭. (Credit: Sophie Davidson)

1. How long did it take you to write Magnolia 木蘭?

From start to finish, it took about three years for the collection to come together. But it’s hard to pinpoint a moment when I started writing this book, because I think a part of me has always known that I would one day write a “Shanghai book.” I lived in Shanghai as a teenager and later returned there to study Mandarin in my twenties. So I felt for a long time that there was a project brewing in me—or numerous projects—exploring my connection to the city. I just didn’t know what form it would take. And it was only after leaving Shanghai that I began to gather the poems and fragments into a coherent collection.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I’m conscious that we write about places differently depending on the distance between us and that place; I’m talking about both emotional and physical distance. I find it hard to write about certain places when I’m in them. There are a lot of poems in this collection about Wellington, the city in Aotearoa, New Zealand, where I was born, that were written when I was far away from home. It was challenging trying to capture this feeling of dislocation while also exploring—or even exposing—the layers of nostalgia and unreality that can blur our memories of a place. I don’t trust my own recollections 100 percent. I’m interested in writing into this in-between space, this slippage of memory.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I don’t have a set routine; it’s always shifted around according to different circumstances: family, work, mental health. I don’t write every day, and I don’t believe you need to. Sometimes I don’t write for weeks but I have ideas pinging around in my brain, or not even really ideas, but images and half-formed things. Going for walks and swims helps these ideas take shape, and then I take frenzied notes on my phone. I’m good with deadlines, so if I’m struggling I need to set a deadline for myself.

When I go through an extended period of not working on any big writing projects, I try to make sure I’m reading as much as possible: poetry, preferably, but almost anything. Reading unlocks something in my brain and is a gentle way of easing myself back into creativity.

I’ve never had my own writing space until just a few weeks ago, when I moved into a new flat in London with my partner and our cat and dog. My writing desk doubles as a sewing desk.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading a beautiful new reissue of Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks. One of my favourite subgenres is “novels by poets.” It’s even better if it’s a novella because I love short books.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I printed out all the poems and rearranged them on the floor of my living room for a long time, trying to see a pattern or make a shape out of them. I realised that the shape of the book was in no way linear, and that the sequence “Field notes on a downpour” lay at the heart of the book, so that had to be in the middle. I ended up arranging the other poems around that sequence—around the “downpour.” The other pieces sort of fell into place after that, and I ended up with a geographical structure, both physical and emotional.

6. How did you arrive at the title Magnolia 木蘭 for this collection?

The white magnolia is the official flower of the city of Shanghai. Magnolias also bloom all over Wellington—pink ones, mostly. For a few months I lived in an apartment in Shanghai overlooking a tall, dark magnolia tree, so the flower will always be emblematic to me. If you have some knowledge of Chinese, then you’ll look at the title and understand that “magnolia” in Mandarin is “mulan.” It was important to me to incorporate hànzì into the title too.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Magnolia 木蘭?

I was surprised by my own tendency to write longer and longer lines and to frequently slip into prose poems. I think I was discovering that the boundaries of genre, for me, are very slippery. I’m more interested in hybrid texts and fragments that are difficult to categorise.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Magnolia 木蘭, what would you say?

Take your time; there’s no rush. And it’s all right if later on you feel a little cringey about some of your earliest poems, as if they don’t belong to you anymore; they’re of another time in your life, a product of your younger self.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Making playlists, cooking for myself and for family, taking morning walks, looking at art, writing e-mails to friends far away, reading lots and lots of poetry, standing between the aisles of Asian supermarkets, and going out to eat alone in noodle shops.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

To be a writer you need to be a reader first.