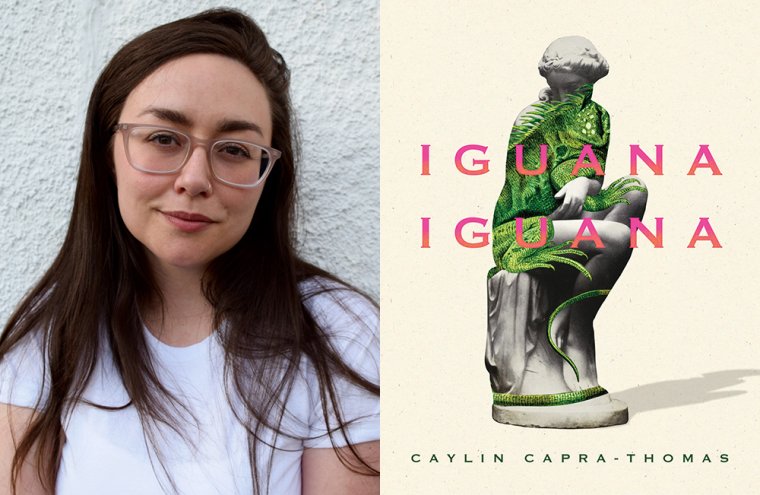

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Caylin Capra-Thomas, whose debut full-length poetry collection, Iguana Iguana, is out today from Deep Vellum. Capra-Thomas’s witty lyrics blend the mundane and surreal, dramatizing the way a mind makes strange meaning of its surroundings and encounters. Lines weave strands of personal experience, pop culture, and philosophical reflection to assemble a multiplicitous sense of self and relationship to others. In “Michelle Pfeiffer Is Making Something of a Comeback,” for example, the speaker realizes that she, too, is “waiting / for something like a comeback / or at least to sign a new lease.” Humor serves as a counterpoint to the underlying sense of dread that haunts the collection: “thoughts fermenting like vinegar, like / the flies that once burst into being behind the cupboard— / something dead back there.” But existential terror bucks up against beauty, rescuing the speaker from falling off the cliff of cynicism she perpetually skirts: “It’s amazing / what you can do with a little light // and attention—who knew.” Poet Diane Seuss calls Iguana Iguana “the kind of book, rare indeed, that makes me fall in love with the ‘I’ all over again.” Caylin Capra-Thomas is the author of the chapbooks Inside My Electric City (YesYes Books, 2016) and The Marilyn Letters (dancing girl press, 2013). The 2018–2020 poet-in-residence at Idyllwild Arts Academy, she is a PhD student in English and creative writing at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Caylin Capra-Thomas, author of Iguana Iguana.

1. How long did it take you to write Iguana Iguana?

The oldest poems in the collection are from 2014, and the newest poems are from January 2021. That means it took me seven years to write, but it’s more like it took seven years for all of this book’s poems to arrive. A lot of that time was spent not composing this book’s poems—composing other poems, composing essays, working, living, and moving, moving, moving. I wrote some of the poems while earning my MFA in Montana, some while living in Gainesville, Florida, some in Cincinnati, some in Idyllwild, California, and then finally in a suite here in Columbia, Missouri. Different versions of this book have come into being and fallen away with each move. At some point, I stopped working on it as a book, started working on a completely different book, and in between thought of myself as just writing poems—loose-leaf, unfated. I needed to live all of the change and movement and multiplicity that the book wound up being about in order to write it.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Finding the thread. This did not begin as a project book, where I had a unified theme or approach. I was just writing poems for seven years and then trying to figure out what they had in common—trying, really, to figure out what the last seven, disparate-seeming years of my life had in common, or what made my life cohere, beyond the fact that I was its protagonist.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I struggle to find routines—in writing, or in any other aspect of my life—but I did get close to a perfect at-home writing routine in Montana when I found myself one spring semester with three-day weekends. I had a two-room studio apartment with stolen Wi-Fi, and I’d wake up on Fridays, make coffee and an egg sandwich, and read a book of poems aloud to myself cover to cover, jotting down words and ideas as I went. Then I’d give myself the rest of the day—however long it took—to write a poem. It was luxurious, giving a whole day to the making of one poem, spending that day alone with poems (and so, not alone), looking out the window at the mountains beyond my makeshift palace. Everything in that apartment was cobbled together—found on the street or passed down by other students or thrifted or yard-saled, my curtains made of bedsheets, my headboard made of palette wood. Everything in that room had a backstory, or had belonged to someone else before me, and it feels right to have begun making my own contribution to a poetic lineage in that environment.

4. What are you reading right now?

Adrian Shirk’s Heaven Is a Place on Earth: Searching for an American Utopia; Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway; Craig Santos Perez’s from unincorporated territory: [saina]; Anni Liu’s Border Vista; and Camille T. Dungy’s Trophic Cascade. I’ve always got several books going at once—perhaps this is why it feels like I move through them so slowly!

5. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Iguana Iguana?

I was surprised that it finally came into being and coalesced around a guiding notion, as I had given up on the book in its original iteration for a few years before returning to it.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

A combination of a distractable, anxious brain prone to procrastination, a tendency to prioritize meeting my external commitments before permitting myself creative time, and the upkeep of my life outside writing.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My fantastic and generous editor, Sebastián Páramo, said so many sharp, insightful things that it’s difficult to distill them. Most important, he told me one thing I already knew but didn’t want to be true—since it would mean I needed to do the hard work of more writing, rewriting, and revising—which was that the manuscript in its original form needed a through-line. “Where’s the soul?” he asked. A body of text without a soul is just a ragtag collection of appendages. He was also the first to locate the pulse the book needed when he pointed out that strangers came up a lot in the poems: meeting strangers, being a stranger to people we meet, and being a stranger to oneself. That’s when it clicked, and I understood what I had been writing for all these years.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Iguana Iguana, what would you say?

I’d tell her, “The thing you’re doing to try to find the book—searching, moving, reinventing yourself every year—is the book.” But you know, even if I could, I wouldn’t go back in time and tell her this. The fact that I didn’t know—this was why I wrote the poems.

9. How did you know when the book was finished?

It was due! I could poke and prod at something forever. I’ll probably be revising on my deathbed, or my ghost will haunt some future unfortunate writer into changing a “but” to an “and.” So I find the forced finality of deadlines necessary. They help me loosen my grip on the poem so that it can go mean whatever it’s going to mean in the world.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

In an interview with Devil’s Lake, when asked to describe her writing practice, the poet Beth Bachmann said, “I’m not sure where the writing begins and ends. I don’t write every day. I write all the time.” In a recent visit to my classroom at the University of Missouri, the poet Jamaal May said something similar—that we tend exclusively to call putting pen to paper—or fingers to keyboard—“writing” and thus place a higher value on that act of composition, when a lot of what we do around the act of composing is also writing. Noticing, listening, reading long Wikipedia articles about whales. Dipping down into our memories, daydreaming, pacing the house having one-sided pretend arguments. Or those moments where you stop what you’re doing to retrieve some item only to find that you’ve forgotten what you were looking for, and there you are, standing alone in the kitchen again, not knowing what you’re supposed to do. What would any of us write about if we didn’t do anything but write?

To balance that out, though, I also often think of this nugget from Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town: Lectures and Essays on Poetry and Writing: “Actually, the hard work you do on one poem is put in on all poems. The hard work on the first poem is responsible for the sudden ease of the second. If you just sit around waiting for the easy ones, nothing will come.” I have internalized this as the slightly abridged motto: Work on one poem is work on all poems.

And one more from Hugo: “At all times keep your crap detector on.”