This week’s installment of Ten Questions features José Olivarez and David Ruano González, the author and the translator of Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro, out today from Henry Holt. In this double volume, Olivarez’s original English poetry collection is followed by Ruano’s translation of the entire manuscript into Spanish. An ode to friendship, family, heritage, and romance, the collection contemplates the meaning of promises: those we make to ourselves and to one another, both interpersonally and on a global scale. Inflected with the urgency of having lived through the global COVID-19 crisis, the collection also asks readers to consider pandemic as a concept that extends beyond bodily illness to the sociocultural plagues of capitalism, colonialism, and toxic masculinity. Diaspora is also at the heart of this collection, as the poems chart the nuances of Mexican identity. In his deft translation, Ruano not only renders Olivarez’s English into Spanish but “the experiences of a Mexican from Chicago...into the Spanish of a Mexicano who lives in Mexico,” as he puts it in his translator’s note. José Olivarez is the son of Mexican immigrants. His debut book of poems, Citizen Illegal (Haymarket Books, 2018), won the 2018 Chicago Review of Books Awards in poetry. Along with Felicia Chavez and Willie Perdomo, he coedited the poetry anthology The BreakBeat Poets Vol. 4: LatiNext (Haymarket Books, 2020) and cohosts the poetry podcast The Poetry Gods. David Ruano González is a Mexican poet, translator, and cultural manager based in Mexico City. A poetry fellow at the Foundation for Mexican Literature (2014–2015), he is the founder of Melancholy of Forgotten Tapes, an independent label/publishing company. Currently part of MAKE Literary Production’s Lit & Luz Festival of Language, Literature, and Art, Ruano publishes his own translations on his blog, medoriorules.medium.com.

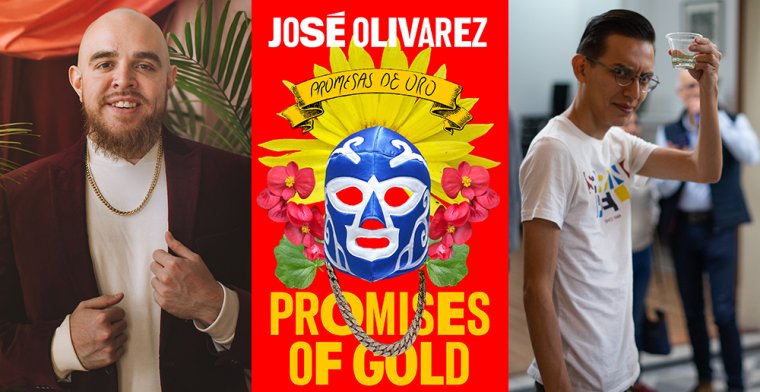

José Olivarez and David Ruano González, the author and the translator of Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro. (Credit: Olivarez: Mercedes Zapata; González: Harrison Martin)

1. How long did it take you to complete work on Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro?

José Olivarez: I wrote Promises of Gold over the course of four years, in starts and stutters. Sometimes I was writing every day, and sometimes I was going long stretches of time without writing.

David Ruano González: This translation had different moments. José came to Mexico City for the second time in November 2019, and for a reading that I made for him and other Chicano poets (Joseph Rios and Alana de Hinojosa) that time, I did the translation of some poems that are now in Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro. In February 2022, I did another translation, so the editor knew my work. After that, I worked on the first manuscript from April to the end of May. And after that, to be honest, I don’t remember what happened. I remember adding more poems, and doing more and more corrections, so I think I finished the process of the book probably in October.

2. What was the most challenging thing about the project?

José Olivarez: This is my second book of poems, so the most challenging aspect was that I didn’t want to replicate my first book of poems. I’m proud of Citizen Illegal, and I wanted to write away from that project toward other themes and with other craft sensibilities. I experimented a lot before I found a groove that felt exciting and new to me.

David Ruano González: I think that it was the simple fact of working with a U.S. publisher. Of course I’ve worked with Mexican publishers before, but never with one from the U.S. and so big like Henry Holt. And another challenge was writing my translator’s note in English. I am used to writing e-mails in English, but not complex texts like this.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write or translate?

José Olivarez: I write in the mornings when my head is less clouded by e-mails and bills and the anxiety of my to-do list. I write at my kitchen table. I have a desk, but the vibes are better at the kitchen table. I write with hot coffee—always Bustelo. When I am writing, I write every day. The consistency helps me stay grounded and in tune.

David Ruano González: As a freelancer, I always work from home. For Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro, usually I started to work around noon and finished around 4:00 PM, and sometimes returned at 6:00 PM and finished at around 10:00 PM. But for my own projects, usually I start a poem around 7:00 PM and I work on it until 10:00 PM. This schedule applies to my translations “for pleasure.” Last year I translated five poems from frank: sonnets by Diane Seuss, but I didn’t publish them yet.

4. What are you reading right now?

José Olivarez: Right now, I am reading Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else) by Olúfémi O. Táíwò. It’s excellent. I’ve been highlighting a lot of passages. I’m also reading Black Women Writers at Work, edited by Claudia Tate, and a book of poems called Never Catch Me by Darius Simpson.

David Ruano González: I’m a chaotic reader, I’m always reading a lot of things and never finish a book in its specific order. Further, I do a lot of rereadings, for any reason. For example, because Charles Simic died recently, I returned to his work, sometimes in translation and sometimes in English. Or because I watched the movie Los adioses (or The Eternal Feminine, in English) again on the TV—a movie about the Mexican poet Rosario Castellanos—I read Castellanos’s work again. I’m reading Kim Addonizio’s last book, Now We’re Getting Somewhere, and Tell Me again, my favorite (Tell Me had a fantastic Mexican translation, called Dímelo). On the other hand, because of my seven-year-old niece, I read a lot of children’s books. My last favorites were The Soul Bird by Michal Snunit, Little Magic Horse by Peter Ershoff, a beautiful Russian tale, and the Crayons series by Drew Daywalt and illustrator Oliver Jeffers; obviously, this is in its Mexican edition.

5. Which author writing outside of English, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

José Olivarez: Raúl Zurita.

David Ruano González: I think that two of the most important and biggest authors of Mexico of the twentieth century are almost unknown. The first one is Abigael Bohórquez, a poet and playwright who always was relegated [to the margins] because he was gay and sympathized with socialism; Bohórquez was a rebel in his life and work, and he was one the first poets who talked about his homosexuality openly. Further, he tried experimental linguistic forms—taking words from the Nahuatl or from the ancient Spanish—all of this with an explicit homoerotic poetics. And on the other hand, there is Esther Seligson. Daughter of Jewish immigrants, Seligson is a very complicated author because in her work you can find topics like myths, reincarnation, dreams, Kabbalah, alchemy, Hinduism, etcetera—all of this combined with a hard style, a prose full of extended sentences, coordinate and subordinate clauses, inspired by Marcel Proust, and a pretty poetic language. When you read Esther Seligson for the first time, the feeling that you have is, “I don’t understand what I’m reading; the only thing that I know is that it’s beautiful.” I could talk about Abigael and Esther for hours.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the work on Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro?

José Olivarez: I wanted to write a book of different types of love poems. The first surprise was how much loneliness and grief crept into the language. The second surprise was that said language didn’t undermine the love in the poems, but strengthened it.

David Ruano González: One thing is to know, and another one is to be aware. Colonialism exists and it doesn’t stop. Everyone knows that. But you live that knowledge in a different way when you start to watch around how it’s present in your daily life. Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro helped me to think about it; for example, I started to think about why my childhood and José’s were so similar if we were in different countries. Today, colonialism isn’t some Europeans coming in ships; it could be commercial trade between countries, a church during your childhood, or a pair of shoes that your parents can’t pay for.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

José Olivarez: I was having trouble writing poems about my parents. My editor, Retha Powers, and I both agreed that familial love was important to completing the arc of the book. Retha and I had multiple conversations where she helped guide me towards some possible pathways to writing about my parents.

David Ruano González: I think I’m José’s friend not only because I was his first translator and because we share Mexican roots. I didn’t need to be born in an immigrant family to know racism and classism here in Mexico, as he did in Chicago. I’m a moreno who comes from a non-privileged family. That’s no good in the Mexican literary world. Even in the labor world, when you are someone like me, you have a limit in your career. You can’t aspire to more; it doesn’t matter how good you are. If I’m still in the literary environment, it’s because of people from the U.S. who believed in me. And for that reason, when editor Retha Powers told me, “I hope to work with you again, it was a pleasure,” I knew that I was not the problem. Something that I say to my family constantly is, “I’m amazed how the people from the U.S. believe in me more than my people do.” And I will be grateful for that all my life.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your creative life?

José Olivarez: The biggest impediment to my creative life is capitalism. In order to write, I often must do a number of noncreative tasks in order to pay my bills and assure I have time and space to write. The stress and anxiety of life under capitalism also impedes my creativity. When I didn’t have health insurance, there wasn’t anything to write except all the mundane ways I could die and be buried with my debts.

David Ruano González: Home tasks! Hahaha. I don’t know. Last year, I could have answered that I needed more solitude for writing because, from 2019 until April 2022, I was writing a collection of poems. During the pandemic it was hard writing poems with all my family in the house. But after that collection, I felt dry of ideas, and now I’m fine and at peace with my creative work. But if I start writing poems again, probably I’ll answer: home tasks and the need for more solitude.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

José Olivarez: In order to write this book, I had to go on many walks in my neighborhood. Often, the poems began during those walks. In Harlem, there was a loneliness that walked with me that revealed the grief I was carrying. In Harlem, there were the chrysanthemums near the first apartment my wife and I shared. Those flowers helped me write. Other walks revealed particular slants of light. How I wanted to hold that light and adorn myself with it.

David Ruano González: At the beginning of 2022, I started to learn juggling, and it’s a practice that I’ve done since then. And with a part of the first payment for this translation, I purchased a unicycle; but I left it after three weeks because I fell down hard, and all my trust was broken. For juggling and the unicycle, you need balance, and it’s a thing that I searched for during 2022. So I think that it helped me to finish this translation.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

José Olivarez: The best piece of writing advice I ever received was to build a writing routine. Inspiration is fickle and unreliable. Routine is consistent and can be counted on. When you write with routine, you make space for imagination to thrive.

David Ruano González: I think it’s a draw. The first one was, “Please stop reading poetry from the U.S.” Obviously I didn’t follow it. And the second one was, “A perfect text doesn’t exist; it will always have mistakes, but you must make mistakes that only you could make.” In the first case, I believed in my heart or intuition—whatever you want to name it. In the second case, I think that these mistakes come from your intuition: that thing that everyone tells you is wrong, but you know that it’s important, a central piece of the text. This doesn’t apply to writing only, but to life too. And you need to learn to defend it. If I didn’t learn to defend my hunger for non-Spanish language poetry, I’d never have published my translation of Promises of Gold / Promesas de oro, or I’d never have known about the Lit & Luz Festival, where I work and met José Olivarez in person.