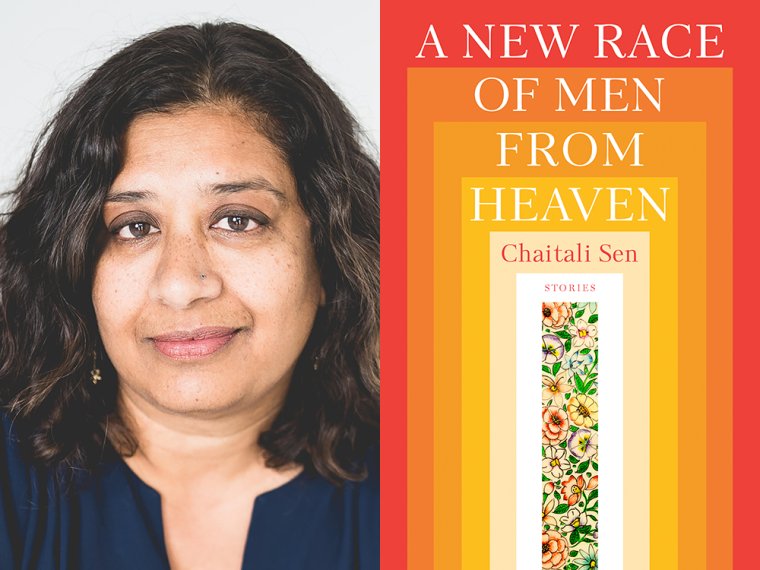

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Chaitali Sen, whose story collection, A New Race of Men From Heaven, is out today from Sarabande Books. In this winner of the 2021 Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction, characters find themselves adrift and longing for companionship and understanding. In a world where physical borders are at times more porous than social ones, their quests for love, friendship, or self-knowledge are circuitous and take them in surprising directions. In “The Immigrant,” a romantically frustrated Indian man finds himself despairing over the fate of a lost boy whose family he encounters at a strip mall in Texas, where he recalls his own childhood experience of dislocation. In another tale, “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” a college secretary gets caught up in the personal lives of her department head and his wife as a war of ideas whirls around campus. In the title story, an infatuation with a man at work triggers a twenty-eight-year-old British woman’s grief over her long-dead father—who, she learns, had his own relationship struggles. “I was captivated by this collection’s interest in disappearances,” writes Danielle Evans, who selected Sen’s book for the Mary McCarthy Prize. “But while the possibility of vanishing haunts these stories, I was struck just as much by their tenderness and luminous moments of unexpected discovery.” Chaitali Sen is the author of the novel The Pathless Sky (Europa Editions, 2015). Her stories and essays have appeared in Boulevard, Ecotone, New England Review, New Ohio Review, and other publications.

Chaitali Sen, author of A New Race of Men From Heaven. (Credit: Paige Wilks)

1. How long did it take you to write A New Race of Men From Heaven?

I’ve consciously been trying to curate stories into a collection for about five years, but the stories themselves took a much longer time. The oldest in this collection is “Uma,” which I started writing in the late 1990s. It was the first story I workshopped in my MFA program with Peter Carey at Hunter College, and it was the story that taught me how to write more stories. For the longest time, I was afraid I was just writing the same story over and over again, but it turns out that kind of thematic obsession helps shape a story collection.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The hardest thing was writing each individual story. I’m slow at short stories, and many of these eight stories took me years to get right. The characters take their time coming to life, and I have to experiment a lot with different scenes and situations. I’m never quite sure what should happen in a short story until very late drafts, and that process for me can’t be rushed. It all comes together in its own time.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

In bed with a cup of coffee next to me. I’ve tried to set up all kinds of inviting writing spaces, but my bed seems to be the most productive spot, mainly because my concentration is best shortly after waking up and before I have to talk to anyone. That said, when I have too many requirements or expectations of my writing space or routine, I find ready excuses not to write, and that can become a vicious cycle. So I try to engage with my writing every day, whether I was able to do my morning writing or not. I tell myself to just open the document, and luckily I’ve never opened the document without composing at least one new sentence. If I don’t actually write, I try to spend time in my head with my characters, hoping to discover something about them or solve a problem with the manuscript.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading the novel Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion by Bushra Rehman, which I knew would be an emotional and lyrical tour-de-force. I’ve been following Bushra’s writing since the late 1990s, when we met through the South Asian Women’s Creative Collective in New York, and I’m happy we’ll be reuniting for book-launch events in February: in Los Angeles at Skylight Books and in San Francisco at The Ruby, a community arts space in the Mission District.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

I’ve read so many good short story collections in the last ten years that have taught and inspired me. I either listen to or read at least one short story a day, and I think we may be in a heyday of short-story writing. Danielle Evans, who chose this collection for the Mary McCarthy Prize, is my guiding star, and I asked for blurbs from people whose short stories are meaningful to me— Elizabeth McCracken, Chinelo Okparanta, Shobha Rao, Clare Beams, Morgan Talty, Oscar Cásares, Karen Bender, and Chanelle Benz. What I love about all of these writers is how they play with readers’ expectations and sympathies and leave me feeling like I’ve been elevated to a new plane of understanding and empathy. I also love their cheeky humor, expecially when mixed with pathos and tragedy.

6. What have you learned about the publishing industry that you wish you’d known before you published this book?

Any time is a good time to know how much great literature is coming from small presses. People are always saying how the big publishers are not interested in short stories. This is not to discount the wonderful collections that do rarely come from the Big Five, but most of my favorite collections come from independent presses like Sarabande.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of A New Race of Men From Heaven?

It surprised me how much research goes into writing short stories. Each story is a different world that requires research both for inspiration and verisimilitude. Sometimes it’s that one bit of research that takes the story to the next level. I love doing research, so this was a nice surprise.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you wrote A New Race of Men From Heaven, what would you say?

Stay curious, pay attention, and write things down. You never know what will end up in a story. You also never know what you’ll want to remember and what you’ll forget, especially as you get older.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Quite literally, all the work that I did over the years—teaching elementary school, temping at an architectural engineering firm, answering phones in an academic department office, and the day-to-day labor of family and social life—found its way into these stories. Living is important. Experiencing the world so you have something to say is important. Also, walking. I figure out a lot of things as I walk.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I think it was advice that was particular to my weakness as a writer. I was in a workshop with Helen Benedict in Paris, and she said, “Don’t make your characters too much like yourself.” This simple advice helped me identify the reason I most often get stuck as a writer. When I ask myself not what I would do in this situation but what my character would do, and when I put my characters in situations that my risk-averse self would probably avoid in real life, suddenly the whole world of the story opens up.