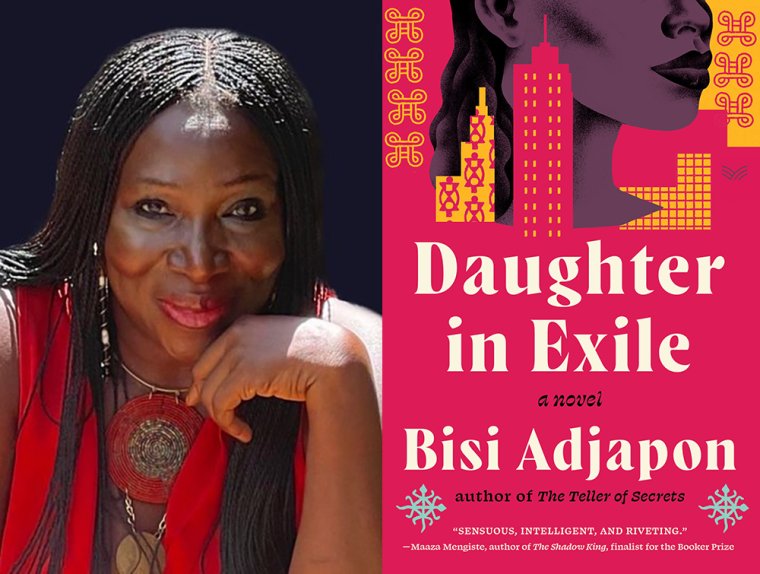

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Bisi Adjapon, whose novel Daughter in Exile is out today from HarperVia. In this international family drama, a Ghanian woman named Lola defies her mother’s wishes and leaves her comfortable life as an embassy worker in Senegal to follow the man she loves to the United States after becoming pregnant. When her tourist visa expires and her relationship ends, Lola faces a far more precarious existence in late-1990s America than she did in Dakar, where her university education and social network functioned as a safety net she had taken for granted. A decade passes as Lola struggles to make ends meet, mother her son, and avoid deportation—until a final trial in 2007 will determine whether she will be forced to return to Ghana and leave the country where she has tried to forge her own path. Publishers Weekly calls Daughter in Exile a “wrenching story of migration, disillusionment, and resilience.... Adjapon continues to dazzle.” Bisi Adjapon is the author of The Teller of Secrets (HarperVia, 2021). Her writing has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and elsewhere.

Bisi Adjapon, author of Daughter in Exile. (Credit: David Wilson)

1. How long did it take you to write Daughter in Exile?

Daughter in Exile was actually the first book I wrote. I started it way back in 2008. Although it went through several iterations, I remained unhappy with my writing. What’s more, it had been rejected. No one seemed interested in stories that had immigration as a theme, so I abandoned it and went on to pen The Teller of Secrets, originally titled Of Women and Frogs. In mid 2018, after we had finished production of Teller, I decided to resurrect Daughter in Exile. I performed major surgery on it, and by the end of the year I had strung together a draft I was thrilled with. I spent the better part of two years rewriting. Then in 2020, shortly after securing an agent, COVID hit. That was paralyzing. Somehow, my agent got me to do two more rewrites. So yes, Daughter in Exile took a long road to get here!

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I wanted to create a beautiful but complex mother-daughter relationship. In order to portray realistic scenes, I had to imagine every incident happening to me. Frankly, a couple did, which meant remembering. I’m someone who treasures the little time I had with my own mother, and precious years with my loving stepmother, and certain scenes reduced me to tears. We have Lola and her charming, no-nonsense mother, and then we have Lola with her own journey into motherhood. It was emotionally draining. Often, I had to take breaks to still my heart. Listen to music. Go dancing.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I find I’m most productive in the mornings. I love to write as soon as I get some coffee inside me. At the same time, I couldn’t stop playing tennis in the mornings. It used to be difficult juggling my two addictions. Now I’ve taken to waking up as early as 4:00 AM. I write for about an hour or two, then head for the tennis court. I play for a couple of hours, come home, shower and nap. After that, if I’m not too distracted by phone calls and pressing matters, I write again until about two in the afternoon. My creative cycle is such that anything that doesn’t get done before then simply doesn’t get done.

When it comes to where I write, I’m supposed to work in my study, this beautiful room with book cases, a cute desk and chair. But I seldom use it. I like to be surrounded by nature, so I often end up writing at the dining table, facing the window, so that when I raise my eyes, I can see trees and greenery. I just love the illusion of being outdoors. I wish I could say that I write every single day. I don’t, but I try. When I feel energized, I write almost daily. Other times, I wake up and just want to read or go for walks with a friend. Writing demands a lot of aloneness, which isn’t easy for a social butterfly like me. It’s a balancing act.

4. What are you reading right now?

I tend to read several books at once. In the day time, I disappear into Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s The First Woman. Her writing has me reflecting a lot and it affects me deeply. I’m also reading The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo, the biography of Alexandre Dumas’ father. I had no idea he was biracial. At first, it was highly entertaining and informative. Now I’m more than halfway through and, from the prologue, I know awful things are going to happen to him. It scares me. I’ve fallen in love with him and don’t want to see him suffer, so I’m reading slowly, trying to postpone the inevitable. Because I’m working on a historical novel, I’ve also been reading a lot about Ghana’s history, sections I had hitherto been ignorant of. All this keeps my mind churning, so if I have to read in bed, I turn to something light and entertaining that won’t give me nightmares. Sometimes I find myself rereading Confessions of a Shopaholic.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

So many! For writing with raw honesty, I’ve drawn inspiration from Erica Jong, Mona Eltahawy, Frank McCourt, Mary Karr, Mariama Bâ, Nawal El Saawadi, Peter Abrahams. Writers like Maaza Mengiste, Helon Habila and Rémy Ngamije—just to name a handful—have taught me to dare to experiment with different narrative styles, to push boundaries. I love dialogue, so plays have been inspirational. One of my favorite playwrights is Ola Rotimi. Lola Shoneyin’s novel The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives is filled with such great dialogue that it has been dramatized many times. Ken Follet once gave me advice about writing sex scenes, and I found it most helpful. I’ve been inspired by writers who tap deeply emotional issues, writers like Tope Folarin, Chimamanda Adichie, Abraham Verghese, Ayobami Adebayo and Chimeka Garricks. Garricks’ writing is spare, and yet he can make you soar with joy or wrench your heart. Ayesha Harruna Attah is another person whose writing has been inspirational, especially her The Deep Blue Between. She is so prolific. No matter what’s going on in the world, she keeps writing. It’s wonderful to be surrounded by talent. When I read a great piece of writing, I find myself filled with gratitude to the author for sharing their gift.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Daughter in Exile?

How a character could go off in an unexpected direction and threaten to derail the whole story. Whenever I start a story, it’s almost like a movie in my head. I usually have a title. I know how the story begins and how it’s going to end. Daughter in Exile surprised me because the beginning changed several times, and the story itself took such a different shape that I almost changed the title. Even the end changed a bit, all because I created this character called Rob, who became such an interesting, crucial person.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

I was sitting in my sunny study in Ghana, behind an old computer, you know, one of those large desktops with a huge head like an old black-and-white television. I had no laptop then. I had moved to Ghana for about three years and was feeling a bit alienated, as though torn between my life in America and that in Ghana. I remember feeling dissociated and wondering what it felt like to be in exile, and just like that, I started writing.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Daughter in Exile, what would you say?

Don’t rush to get a draft finished. Take your time. Sit with your characters and let them talk to you. It’s okay to throw away the whole manuscript, or at least save it somewhere, and start again. Also, for goodness sake, don’t be afraid of your creativity. Remember, there is only one of you, with a unique voice. Your voice is a necessary addition to the literary discourse. Use it!

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I had to research Adinkra, symbols that represent nuggets of wisdom for the Akan people and, by extension, all Ghanaians. Although I had grown up knowing a couple of symbols, I was ignorant of their depth of meaning, their variety, and how they could absorb a whole society. I examined them closely and was awed by their beauty. I worked them into every chapter of the book. I love that.

Another thing I did was revisit Dakar. It’s a beautiful peninsula on the tip of the West African coast, one of my favorite places on earth. I wanted my main character, Lola, to enjoy its rhythm and romance. I visited Ngor Island, smelled the salt and watched fishermen mend their nets. I ate their couscous, went dancing, and remembered what it was like to be twenty again, living on my own with a roommate in that charming city.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I don’t know that I can single out only one. I’ve been fortunate to be acquainted with many generous writers who share their wisdom with me. One piece of advice that stands out came from Laurie Viera Rigler, author of Confessions of a Jane Austen Addict. She told me to beware of my inner censor, the voice in my head that keeps asking what people will think or say, the imagined finger-wagging from society. And so I write as if talking to my best friend. I hold nothing back. During the lockdown, I was supposed to be doing some edits for my agent but I found myself in a state of inertia. Daily accounts of the pandemic death toll swamped me. Though I found solace in an online platform, I couldn’t type a creative word. But then Dave Eggers told me to keep writing and to trust in the process, because writing helps to create order out of confusion. It means sometimes writing a poem or painting a picture instead of focusing solely on the work-in-progress. So I try to create every day, even if it’s a doodle, a single line, poem, a song, or two thousand words. I don’t always succeed. The operative word is try—not flagellate myself when I simply can’t. Those are the two pieces of advice I keep close: to keep creating, and silence the inner critic.