This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Maggie Millner, whose debut poetry collection, Couplets: A Love Story, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In this formally virtuosic book that reads like a novel-in-verse, a woman in her late twenties ends a long and steady relationship with a man for a thrilling but destabilizing affair with a woman. Millner evokes the excitement of new love and budding queer sexuality in a masterful merger of form and content: The titular two-line stanzas that construct the bulk of the volume—interspersed with prose poems, each of which ends on a slant-rhymed couplet—offer a study of duality as much as of romance. Couplets considers how coupledom offers an encounter with the uncanny, as the beloved and the self become intertwined, one ever threatening to subsume the other. Millner enthralls as she takes readers through the tortured psychology of attachment, lust, betrayals, jealousy, and the struggle to locate and maintain an authentic sense of identity. “Sexuality is, // after all, a formal concern: / finding for one’s time on earth // a shape that feels more native than imposed,” she writes. Garth Greenwell calls Couplets “an endlessly inventive, wise, exhilarating book.” A senior editor at the Yale Review, Millner teaches writing at Yale University. Her poems have appeared in the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and Poetry.

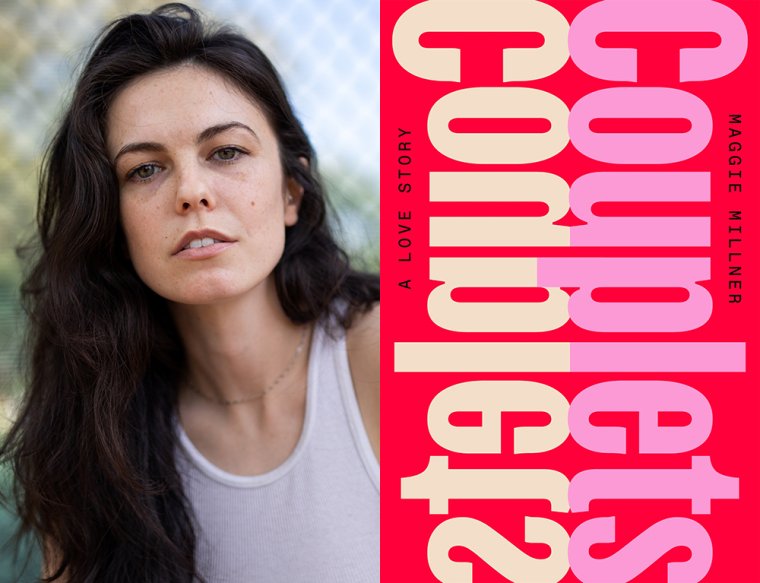

Maggie Millner, author of Couplets. (Credit: Sarah Wagner Miller)

1. How long did it take you to write Couplets?

I wrote the book concertedly for a year and a half. But I ended up recycling a couple older poems, so there’s a distance of about four years between the oldest and the newest sections in the book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I think the hardest part was finding an ending, specifically working against my own desire for neat resolution. I felt myself wanting to close every section on a totalizing insight, and to close the book on some lasting epiphany or summative happily-ever-after gesture. But the story I was telling wasn’t so simple; it wasn’t ultimately about discovering some durable new relationship or self-concept, but rather about renouncing the expectation that truth is something you arrive at conclusively.

This felt especially tricky because I was writing in a form—the rhyming couplet—that both dramatically performs closure and also builds propulsively upon itself. Barbara Herrnstein Smith, in the couplets chapter of her great book Poetic Closure: A Study of How Poems End, sums the problem up this way: “How can formal continuity be maintained in a poem that is generated by a principle which tends to produce closure every two lines? And what can provide the sense of final closure at its conclusion?” That push-pull between conclusion and continuation, and between resolution and openness, made it really difficult for me to know how and where to end the book.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

During the semester, I write about twice a week, at my kitchen table. There’s a lot of black tea involved. I try to write more during the summer and winter, but it doesn’t always work.

4. What are you reading right now?

The Biography of X by Catherine Lacey, which will come out officially in March. It’s wildly ambitious and thrilling on the sentence level.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

“Collection” is maybe a misnomer here; the book comprises one long poem, broken into numbered cantos. On the other hand, it might not be a misnomer at all, since I wrote the sections one at a time, out of sequence. Because the poem is narrative, I knew I had to tell the first half of the story in largely chronological order, though after the book’s midpoint, things become less linear, with more flashbacks and lyric detours. The second half was much harder to organize—mostly I just tried to make each section flow associatively into the next, and to strike a balance between chin-stroking and scene-writing.

6. How did you arrive at the the title Couplets for this collection?

I’ve never been a confident titler of individual poems, let alone of manuscripts! Before I had a working title, I tended to refer to this project in conversation as “my couplets” or “the couplets.” After suffering through countless conversations about it, the poet Noah Baldino suggested that maybe “the couplets” was simply the book’s title—and then another friend, the poet Jessica Laser, told me emphatically to drop the article.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Couplets?

It amazed me to feel patterns of rhyme and meter insinuating themselves into my everyday speech. I would often talk in accidentally rhyming sentences during the time I was writing this book (which my friends and students got a real kick out of). It’s always a thrill to remember that the brain—much like language—is this physical, elastic material that can be coaxed to behave in new ways.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Couplets, what would you say?

Maybe: “Read more noncontemporary books. And publish less. And cultivate an aesthetics based on what you love, rather than what you think is likable.”

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Lots of conversations with friends and family. Lots of reading and therapy. And running—I ran almost daily during the composition of this book.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

When I was in college, the now-late poet C.D. Wright gave me the assignment to write poetry without using any figurative language or grammatical contractions like “can’t” or “I’d.” Of course, I eventually found my way back to these habits, but the exercise taught me something unforgettable about my own stylistic tendencies as a writer. It also showed me that really transformative pedagogy doesn’t give students answers, but rather leads them toward strange new habits of mind.