Recently, when asked for my favorite books of historical fiction, I realized that though I thought of it as occupying the backwaters of both history and fiction, I actually read, enjoy, and admire the genre. Just a summer ago, for example, I had the great pleasure of ignoring all current political news, so enthralled was I by Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869), which was heartbreaking, hilarious, and politically astute, with characters so vivid—including Napoleon—and many of them, their pain so palpable, their friendships so genuine, and their inner lives and demons, so comprehensible, that I felt when I finished that I had lost a world.

But I had blithely assumed I agreed with the character in Austen’s Northanger Abbey (1817) who says, “history, real solemn history I cannot be interested in ... the quarrels of popes and kings, with wars and pestilences in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all.” Of course she’s absolutely right, when fiction—historical or not—is dull and stuffed with fact and extraneous details or contains plots that go nowhere and that land in predictable places. And who would ever be interested in fiction with characters that are stolid and static, like wax figures that in no way resemble real people. That’s simply not good writing.

Yet think of the variety of historical novels that we don’t even call historical: Charles W. Chesnutt’s The Conjure Woman (1899), George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876), Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate (1980), Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End tetralogy (1924–1928), Sybille Bedford’s A Legacy (1956), Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum (1959), Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), or more recently Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), Orhan Pamuk’s My Name Is Red (1998), Hannah Crafts’s The Bondwoman’s Narrative (2002), and David Ebershoff’s The Danish Girl (2000)—just to name a few. Authors of different backgrounds, in different eras, write with passion for secret places as they imagine what it might be like to be or live inside someone else and feel their sorrow or exultation or regret. We experience them with pity or horror or respect.

“Novels arise out of the shortcomings of history,” said Novalis, the eighteenth-century author and philosopher. And all fiction deals in one way or another with time—whether decapitating it or rendering it spatially or simply by allying it with the biological clock and calling the result a plot. But when I thought “historical” fiction, I didn’t immediately imagine worlds elsewhere but rather a place crammed with boring dates and naturalistic detail, where the past was conscripted into a neat and often moralistic tale. How wrong I was, for writers of historical fiction must imagine time in such ways that it feels accessible and vivid. Sure, there was a place, Sicily, where the Risorgimento—Italian reunification—created a single nation, the Kingdom of Italy, in 1861. But Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa in his best-selling The Leopard (Collins and Harvill Press, 1960) converts that history into the story of Prince Salina, Don Fabrizio Corbèra, also known as the Leopard—il Gattopardo. Instead of making the march of time the center of the story, Lampedusa shows how the prince, head of a wealthy family with estates in various parts of Sicily, incarnates the old order—and not as a fossil, but as an intelligent, inquisitive, worldly-wise and essentially lonely man who neither resists change nor fully embraces it. Somewhat reserved, he is unlike his headstrong nephew Tancredi, about whom the prince says that in life he “will have to aim higher, by which of course I mean lower.” And as the center of the novel, he articulates with mixed emotions what history means—to the individual and to the nation—and whether or not we have power to change it. “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change,” Tancredi explains to the prince early on, and the prince agrees, but only to a melancholic extent. History is rise and fall, and we feel so acutely the prince’s fall because we come to know and admire him, even if we care not a bit for the aristocracy he represents. He is, to us, human.

And there is more. There is narrative style, the way a story is told, the “mortar that binds together the different stones and assures the durability of the edifice,” as Lampedusa said of Stendhal, another historical novelist. Without style there is no novel, and in the case of The Leopard, the reader becomes part of the action because the reader knows each character through what is said and not said, through gesture, through the care with which the author dresses the character, through indirection and those pauses when the writer toggles between the fixed and the uncertain. Or the novels show us how we interpret the past as we project ourselves into events that we see through closed doors. The historical novelist helps us to forget ourselves with the images, canny surprises, and coiling sentences that seem to come from within. This is not some historical revisionism; it is craft. With language that is bold and concise, sharp and unforeseen, historical novels enliven through character but also with the sweep of a narrative that, no matter the style, keeps us reading.

Yes, there is suspense in historical fiction. We may or may not know the outcome of the events at hand: What does it matter that the North won the Civil War if Faulkner’s Thomas Sutpen, of Absalom, Absalom! (Random House, 1936), grows from outcast to unreconstructed Southern patriarch who cannot or refuses to see the humanity in anyone else and perhaps not even in himself. Or we may well know that the poet Siegfried Sassoon lived to a ripe old age, but that doesn’t diminish our sense of his moral stature in Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, where he confers with the remarkable psychiatrist W. H. R. Rivers, whose paradoxical duty is to heal men shattered by war’s insanity so that they might return to the front. That is to say, the authors of historical fiction select from the material on record to create a world where character is not set in stone and outcomes are not predetermined—where everything remains uncertain, unknown, perhaps ultimately unknowable or at least yet to be discovered. And to write of what is unknown or startling or unforeseen in ways that are equally startling and fresh is open to any writer, working in any mode, who enjoys how language plays with us even as we play with it, and who recalls, as we all can, that events are often not as they seem, and stories don’t land in a rut. Writing is an adventure—it renews us—and it’s fun even when writing is hard, which it of course always is.

More than one hundred fifty years ago, Henry James wrote an essay about the art of fiction that remains today an important guidepost for all fiction—including the historical novel. And though he had famously said that the historical novel, for him, was “condemned ... to a fatal cheapness,” he knew better. “As the picture is reality, so the novel is history,” he wrote in “The Art of Fiction.” For history that is allowed to represent life was what he was after, as he explained, and the novelist represents life precisely with “the power to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things.” So if we think of history as the seen—which it often is not—we can say that the novelist does in fact guess what lies behind the known, the accepted, the factual, the documented. And in that, historical fiction is alive, vibrating with a past that is in the present, part of the world, part of character, part of us.

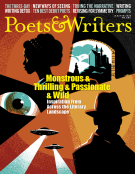

![]()

Venture Further: Consider a narrative you’re confident you understand well, be it personal, historical, or taken from one of today’s headlines. In poetry or prose, relate the narrative again from the point of view of someone with a different stake in the situation. What changes when the perspective shifts? Now write through this situation once more, giving one of the characters involved a secret that explains their actions—or upends what happens next.

Brenda Wineapple is a National Book Critics Award finalist whose most recent book is the best-seller Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial That Riveted a Nation (Random House, 2024). Other books include The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation (Random House, 2019). She has received a Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Pushcart Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a National Endowment in the Humanities Public Scholars grant, among other honors. She teaches in the MFA program at Columbia.

Illustration credit: Matt Stevens; thumbnail: Elena Seibert