The first horror story I remember affecting me deeply was “Survivor Type” by Stephen King, a story in his collection Skeleton Crew, which came out in 1985. Fourteen-year-old me bought that book, in 1986, with my own money, earned during an incredibly short-lived career delivering newspapers in Queens. Maybe I read the book even more closely because I’d spent my own cash on the copy. “Survivor Type” is the story of a surgeon who is smuggling heroin on a cruise ship but becomes marooned on an island and must do whatever he can to survive. What he is willing to do is gruesome almost beyond belief, and when I reached the last page, my immediate reaction was, You can do that in a story?

Often when I’m speaking with newer writers—either my writing students or people I meet at conferences and events—they will mention the conscious, or subconscious, desire for permission. Permission to put their writing goals on the same level of importance as their day job; permission to balance their writing with their parenting obligations; permission to invest time and energy in an artistic goal with no promise of success. There are so many ways the world can sabotage our intentions, and to make things even more complicated, sometimes we’re the ones stopping ourselves. Isn’t it selfish to want to write when others around us need our time and energy? Isn’t it foolish or shortsighted to hold on to this dream?

One of the greatest gifts the horror genre offered me then was a sense of permission. Because I was only fourteen, I didn’t have to weigh concerns about parenting or earning more than some pocket change with my after-school jobs, but I did feel the anchor of respectability. By that I mean, what would my good churchgoing grandma say if I wrote a story about a surgeon who smuggles heroin, crashes on an island, then does some truly unspeakable things? Of course I could only dream of writing something like King’s story, but where should dreams stay? In your damn head. Not typed out on an electric typewriter (again, it was 1986) or written by hand, and certainly not shared with other human beings who might then whisper, Did you read what that LaValle boy wrote?

I did read the entire collection, but the particular effect of “Survivor Type” stayed with me more than nearly every other story in the book, which, if you know that collection, is really saying something. Days later, when I did sit down to try to write a story, haltingly, unsure of how to move from one sentence to the next, one paragraph to another, I returned to the sense of permission I’d felt when I read that piece. With horror, perhaps more than most other kinds of stories—except maybe the work of some of the truly great experimental writers out there—you really can do whatever comes to mind. The worse, the weirder, the better. If you can dream it and describe it, horror will find a place to fit you in.

Okay, you might be saying, “That’s all well and good, but how do you avoid the pitfall of exploitation, being gruesome simply for its own sake?” The genre is often dismissed, by those who don’t read it, as mere indecency. First, I think that’s insulting to indecency, which has its place, and second, horror becomes truly effective only when the freedom, that permission I mentioned, is paired with a deep and relatable, emotional core.

If I think back about some of the most powerful horror fiction I’ve read, I tend to remember a premise that checks off some big horror idea, but it always comes coupled with a much more grounded understanding of a deeply human dilemma. To use King as an example one more time, The Shining (Doubleday, 1977) is the story of a haunted hotel, but it’s also about the horror of discovering you are not the man you thought you would be; the horror of realizing you’ve married a man who will put you and your child at risk; the horror of understanding your own father could kill you.

Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (Viking, 1959) tells the story of a lonely, introverted woman named Eleanor who joins a group of men and women whose goal is to figure out if the titular Hill House is, in fact, haunted. Hijinks ensue. There have been dozens of books, stories, films and TV shows with the same essential premise, and the majority haven’t turned into classics of American literature. The difference is Eleanor.

At the start of the novel, Eleanor lives with her sister’s family. The sisters inherited a car from their mother and are, in theory, co-owners of the vehicle. Eleanor tells her sister and brother-in-law that she hopes to use the car to drive to Hill House, but her sister opposes the idea. What if they need the car? And, besides, should Eleanor be going to strange places with people she doesn’t know? The answer is no. The next morning Eleanor takes the car anyway and makes the first truly independent choice of her life. There will be profound repercussions because of this, and it will take a whole novel to see them through. This is why Jackson’s novel overshadows, in my opinion, all others that mimic the premise.

In both The Shining and The Haunting of Hill House, the premise—a family trapped in a haunted hotel and a lonely woman trapped with others in a haunted mansion—stretches reality and tips into the supernatural, but each premise is then coupled with believable characters who are facing emotional crises that nearly anyone can understand. Jack Torrance of The Shining is a recovering alcoholic and frustrated writer who hoped he’d amount to more than he has; Eleanor Vance is a woman who has never put herself first and wonders if she’ll die having risked nothing. Put those two people in the middle of an outsize situation and you’ve got the potential for a powerful story. The haunted locations will push each character far beyond the limits of real life; and the depth of each character’s emotional story will elevate the scares and jumps from being a lot of noise and nonsense to the kind of trials that test the human soul. It’ll make for one hell of a horror novel, too.

![]()

Venture Further: Describe the greatest fear of the narrator of your story, essay, or poem. What form does this fear take in the world around them? What would this fear look like if it were to manifest in something unnatural?

Victor LaValle is the author of seven works of fiction, including Lone Women (One World, 2023), The Changeling (Spiegel and Grau, 2017), and The Ballad of Black Tom (Tor, 2016). The Changeling was adapted for Apple TV in 2023. He adapted his novel The Devil in Silver (Spiegel and Grau, 2012) as a limited series for AMC. It will air in 2026. He has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the World Fantasy Award, the Bram Stoker Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the key to Southeast Queens.

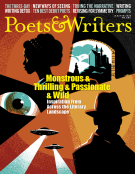

Illustration credit: Matt Stevens; thumbnail: Teddy Wolff