In his wonderful essay “Quickness,” Italo Calvino references a scene about a story told poorly. A woman on horseback, eager to listen to a good yarn, instead writhes in her saddle because of the terrible stopping and starting of the storyteller. The tale cannot roll. The woman’s internal tempo is offended. The story is very funny in part because it’s so recognizable, the unease of broken rhythm like being trapped in stop-and-go traffic on the freeway, but the description is also notable because the woman’s reaction is not just intellectual but physical; she cannot bear a badly told story in her body. I’m sure most of us can relate—how often have I, when an anecdote told at a party is hard to follow, left to find the bathroom? Or have seen others do the same if my sentences trail into nothingness? As listeners we can get itchy, restless. The experience is corporeal.

The inverse is also true: A story well told is as nourishing as a delicious meal, as mind-expanding as an afternoon walk, a boost to both body and spirit. And what type of story might better fit this model than one told over and over again, a nugget of the oral tradition, a piece of folklore? The movements and rhythms of fairy tales have been tested by thousands—millions! billions!—of audiences over time, the beats smoothed and perfected like shards of seashell, edges worn to gloss at the shoreline.

Years ago I taught elementary school, and I read the kids a lot of stories and made up a lot of stories. I found there is no better audience to track listening attention than a gaggle of seven-year-olds on a carpet. Many of my stories were fairy tales, well-known or invented on the spot, and for the new ones, I hurtled forward into the fictional unknown, desperate to keep them quiet, my choices based on their focus as much as anything. The kids would shift around unhappily if I lingered too long on a moment; if I rushed past something, wrestling might ensue. But when they got caught up, they would quiet down, widen their eyes, freeze. We wrote those stories together, in a way. They were the most attuned of editors, writing in the margins of my improvisation with their physicality.

Adults generally need more substance in their stories than kids do, it’s true, and E. M. Forster famously critiques this type of tale, the kind that is just an “and then, and then,” in his comment about plot and causality, about kings and queens and grief. (Just in case: “The king dies then the queen dies” is not nearly as interesting, he states, as “The king dies, then the queen dies of grief” because of how the latter opens up character.) Of course he has a very good point—yes, our reading is almost always deepened by character development and consequence. There is something grown-up in this shift from hitting speedy plot points to studying human motivation, and the layers let us lean in and invest far more.

But I also think Forster’s disdain for “and then” isn’t totally fair because the velocity of a fairy tale is not just about the immediate gratification of moving the story along. Maybe so when on the elementary school rug, but the tales wouldn’t have lasted over centuries if they didn’t contain greater depths. Later, once a story is told, we can look back and think about the plot, about what led to what, and use that footpath of action to consider meaning and interiority. The classic Perrault and Grimm versions of the Bluebeard tale, with its intense sequence—man marries woman, man says don’t go into room, man gives her key, woman goes into room, woman finds dead women in room, woman (or iterations of her) escapes, man is punished—are powerful exactly because the tale in its boiled-down state can apply over time and space to become an ever-relevant way to talk about violence and tests and traps and control and secrets and curiosity and more. It remakes and reforms, applies metaphorically with ease. When stories in the news involve an exposed secret—which happens surprisingly often—I’ve found myself leaning on the story of Bluebeard to organize my thinking, to find the mythic patterns beneath what seems so gritty and sordidly new. Nope.

In part this layering can happen because the tales are so short. The plot points form into spare building blocks, and while the beats are obvious, easy to note, the reasons aren’t always so clear, which makes space for me, the reader, to consider motivations on my own. When the Brothers Grimm’s Hansel and Gretel are left alone in the woods, they get lost and then discover the candy house, and that’s where they use their wits to survive and escape. Abandonment leads to candy leads to witch leads to outwitting. (But why might abandonment lead to candy? How interesting! What psychological lens or thoughts on financial insecurity might apply?) In an earlier Italian telling of Snow White, when the protagonist “dies,” her glass coffin grows with her, so we can see her age under this stretchy glass, sort of dead, sort of alive. What might a reader do with such a strange image? When Sleeping Beauty is kissed by the right person, she and the entire sleeping castle wake up—even, Charles Perrault adds, the kettle on the stove resumes its hissing. This could be, as is often posited, the result of perfect, fated love, but according to psychologist Bruno Bettelheim’s interpretation, maybe the twining thorny vines open because she is ready, and the time spent in adolescence, in passivity, has shifted to an active adulthood.

In fact, the “and then”s in these short tales are so fun to move around in the mind that they can train a reader to look for this type of movement in fiction that does have extensive character development, which then can help us note revealing shifts. In Raven Leilani’s Luster (FSG, 2020), the flow from considering the narrator’s attraction to this guy in her office, to a shift in attention to his wife and to their charged friendship becomes how I know her, how I can map and grasp her desire and yearnings. It’s a deepening plot swerve, where cause leads to a surprising effect, but there’s no doubt about the connection, how one relationship couldn’t exist without the collapse of the first. In Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore (Knopf, 2005), beneath all the complexity of trauma and societal unrest, we can note the changes in the old man, Nakata, who can speak to a cat, and then see, as the book moves along, what and who else he can speak to and how each development startles a reader into questioning what communication means in the first place. I remember reading that book, so energized by this cat-talking plot progression, but without a kind of “training” from fairy tales, I don’t know if I would’ve followed that particular movement so closely, charting the movement of Nakata’s ability the way one might watch the wolf travel down the row from the straw house to the wooden house to the brick house as he tries to eat up the pigs. By the end of the read I felt like Murakami was talking about the trembling power of language itself, so slippery and profound I could hardly hold it in my head.

Years ago one of my students captured the idea of this slippery beauty. We were talking in class about “The Twelve Dancing Princesses.” In the tale the princesses take boats underground past jeweled trees to go dance in a palace, away from their strict father. It’s a powerfully dreamlike image—and then the story ends, a little randomly, with a marriage. Why a marriage? We talked about this in class. And why must it be that the eldest daughter marry a soldier? What’s that about? One student, David, raised his hand. He said he thought the marriage was just a way to wrap up the story so that it looked like a story and could be heard as a story, but really what we wanted and craved was the imagery in the middle, that mysterious difficult-to-interpret underground world of dancing and rebellion. And we need the bookends of “once upon a time” and “happily ever after” to give us access to that amazing series of images. To lure us into the dream.

As writers, we can try the “and then” as a way to go deeper into the woods of the story ourselves. If a trail of “and then”s can take a reader or listener where they never thought they’d go, it can take the writer there too. Later we can fill in motivation if we want to, after we see an arc of movement; we can see if causality tucked itself in the mix on its own; at the very least we’ll have some rich material to work with and expand. What if we think of it as a kind of breadcrumb path of language? It even looks like a breadcrumb on the page. And then...and then...and then...

![]()

Venture Further: Identify a moment in a poem or a plot where you’ve felt stuck. Read the piece out loud, and as you approach the moment that feels inert, instead of reading on, make a swerve—and improvise that swerve on the spot. What’s the most interesting or surprising or thrilling place you could go next?

Aimee Bender is the author of six books of fiction, most recently The Butterfly Lampshade (Doubleday, 2020), longlisted for the PEN/Jean Stein Award and The Color Master (Doubleday, 2013), a New York Times Notable Book. Her short fiction has been published widely in places such as Granta, Harper’s, the Paris Review, and more, and she has linked tales recently published and forthcoming in the two most current issues of Kate Bernheimer’s journal, the Fairy Tale Review. She teaches writing at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

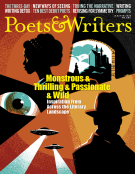

Illustration credit: Matt Stevens; thumbnail: Max S. Gerber