For a decade we’ve devoted space in each November/December issue to celebrate debut authors over the age of fifty with first books published during the current calendar year. The writers in their fifties and sixties spotlit in this issue share their unique literary pathways, reflecting on how they took the leap to overcome their fears, their struggles to wake up with the rising sun and write before the days begin, how sharing the stories of their ancestors awakened their creativity, the importance of perseverance—even when “life has the rotten habit of interfering”—and the triumph of growing up and cultivating one’s calmness. As Princess Joy L. Perry notes, “It is only now that I realize I was a real writer all along. … I was a writer before a publishing company finally said yes to me. So are you.”

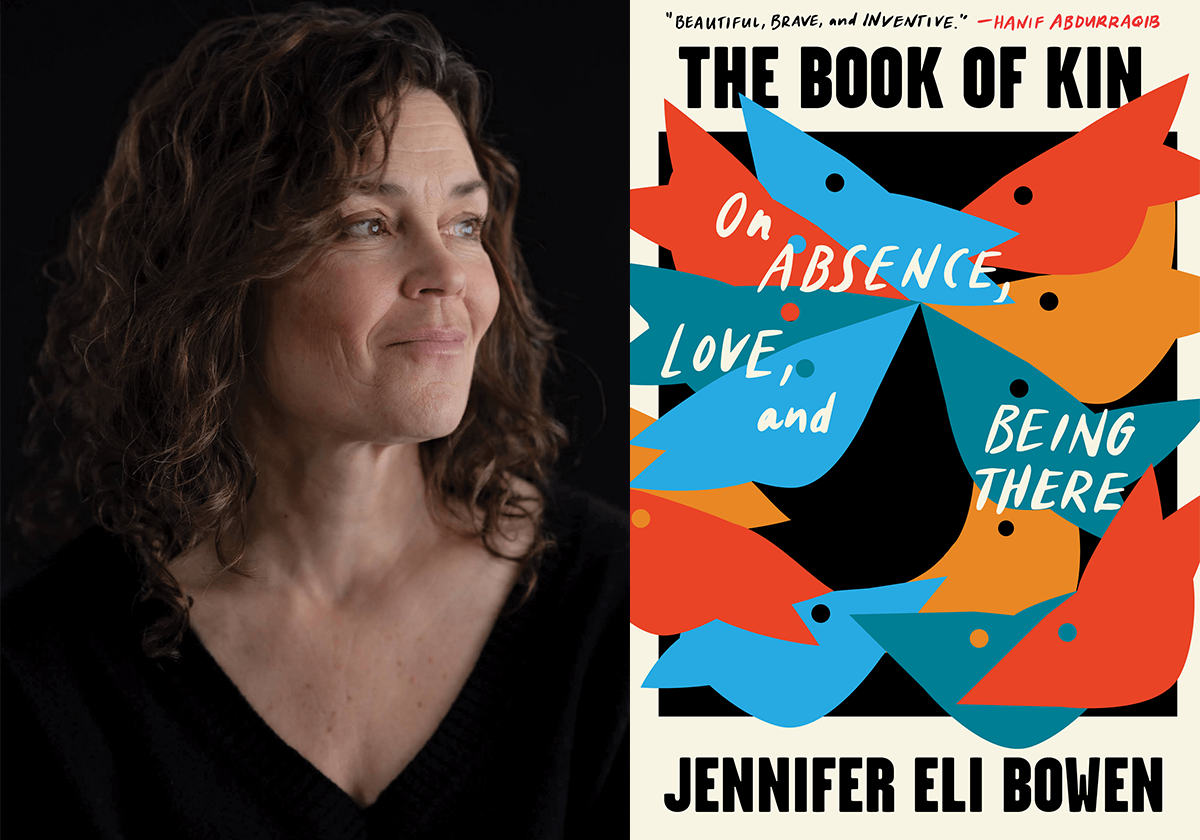

Jennifer Eli Bowen, author of The Book of Kin: On Absence, Love, and Being There (Milkweed Editions)

Princess Joy L. Perry, author of This Here Is Love (Norton)

Yael Valencia Aldana, author of Black Mestiza (University Press of Kentucky)

Vishwas R. Gaitonde, author of On Earth as It Is in Heaven (Orison Books)

Lauren K. Watel, author of Book of Potions (Sarabande Books)

Jennifer Eli Bowen

Age: 52. Residence: Saint Paul. Book: The Book of Kin: On Absence, Love, and Being There (Milkweed Editions, October 2025), an essay collection that explores the many facets of care and community to reveal personal, societal, and systemic truths about human connection and healing. Agent: Jennifer Thompson. Editor: Mary Austin Speaker.

I have long joked that we need more literary prizes for older debut writers. We’re the ones, after all, who are trying to write while forgetting our words. Each year that we don’t finish our books, we work under increasing pressure we might never do so. And I should know.

The first sentence I wrote with serious intent to be a writer is included in my debut essay collection, and I wrote it as an undergraduate at the age of twenty-two in Iowa City. I wrote the last sentence of the book when I was fifty-one, in a tin-roofed guest shed in southern Arizona. In between those two sentences I got married, raised sons, built and codirected a nonprofit. I taught writers, got divorced, took on gig work. I lost people I care about. Grew tired. Stopped drinking. Walked dogs. In other words, I’ve lived a full life.

Gender inequities notwithstanding, lots of authors endure life’s chaos and still manage to publish gorgeous books. We don’t need to make a pissing contest out of our impediments. But if we did, here’s the one I’d win: I am an enormous chicken. My greatest obstacle to finishing a book has probably been my fear.

Trying is scary. As penance for having a dream, I’ve kept mine small over the years. If I dared say something that mattered, I at least did so quietly. One essay, one story, one reader at a time. Baby steps. It brings to mind the only time I jumped off a high dive, at the age of ten. I wanted to jump, but I also wanted to do anything but jump. Because what if I got hurt? Or looked stupid? Or hurt someone else when falling in the water below?

I climbed three rungs up, stopped, and climbed back down, repeatedly. That is, until my stepdad blocked the base of the diving board, refusing to let me retreat. Stuck on a high dive with my swimsuit wedged up my ass, I stood, visibly trembling with no way down but a plunge. Eventually I sat down and scooted the length of the board, then rolled onto my stomach and slid, inch by inch, over the edge.

Such has been my approach, I now realize, toward making a book. I first went to graduate school for journalism, never mind my love of essays and novels and poems. When I began submitting creative work, I did so to the tiniest journals I could find, publishing piecemeal. I wrote essays and stories that said what I needed to say, paying little regard to pesky limitations like time. I would query agents when I had a manuscript ready. When my kids were older. When work slowed down. Fill in the blank for every excuse that actually meant when I’m brave.

Eventually—and this is the sole reason I finished a book and why having only my name on the cover is a lie—my people kindly dragged me into my own becoming: a friend who passed essays along to my now agent (who patiently waited for more pages), my editor, my sons, my therapist, sturdy mentors, and brilliant friends. They didn’t force me off the edge, but they did hold my hand and jump with me.

So now I am launching a geriatric debut. After turning the final page of my manuscript, a friend of mine said, “I hate that you had to live through what you lived through, but it’s like your book was waiting for the current you to arrive. She was the only one who could finish it.”

I promise you if that frightened kid turned elder finished her book across decades and with doubt—feet planted on solid earth, but leaping nonetheless—you can, too.

An excerpt from The Book of Kin: On Absence, Love, and Being There

Surrogates

2.

Al had endured a severely restricted diet for months, but now that he was in hospice care, he could eat what he wanted, and just then what he wanted was salami sliced so thin you could see through it. “Hear me?” he asked with a grin. He motioned with clumsy hands. “That thin!”

I asked the man at the deli to slice the salami like lace. The man, who did not know he was part of a sacred task, adjusted knobs and slid the meat against the spinning blade. When he tossed the first slice onto the scale, it was so thin it did not even register.

I brought it to Al, and he held a slice up to the light, admiring the cut. I’d gotten it right, and he rewarded me with a smile.

We held hands more in his last two days than we had in all our years together. I asked if he was scared, and he said, “Not if you’re here.”

Who is this man? I wondered. Who is he confusing me for?

A few days into my visit, he requested a grilled cheese sandwich—his literal last meal. I placed three different kinds of cheese inside two pieces of Asiago bread and grilled them until the entire house smelled of browned butter. Al said it was the best he’d ever eaten.

“Please, God,” he said, folding his hands and pretending to pray, “let me live one more day so I can eat three more.”

5.

It has been four years since Twin was euthanized. Five years since Al died. I’m solo parenting my own kids, and I doubt I’ll ever remarry. Curious, still, about stepfathers in nature, I type into Google, “surrogate fathers animal world.” There are six. I try “capable stepfathers animal world,” which brings up a list of . . . surrogate mothers. There’s an orangutan who takes in tiger cubs. A Pomeranian who adopts a monkey. A dog who adopts a squirrel, a cat who adopts a squirrel—really every kind of animal willingly adopts squirrels.

My favorite surrogate of them all is the cat, Lurlene, who takes in a pit bull. A fly-infested, one-day-old puppy whimpered from a garbage can. Some woman brushed him off, named him, and tucked him right up against her cat, Lurlene, who was nursing kittens at the time. Lurlene mewed and fed the puppy along with the rest of her litter. In a photo taken a bit later, the puppy is gazing with milky, three-week-old eyes right into Lurlene’s whiskers. There are photos of Lurlene with all her kittens and that starving baby pit bull at her nipples, and their little heads and mouths are all frantic and needy, yet every one of them is being nourished, and Lurlene has this look on her face like, Good God, let it end. She doesn’t leave the cardboard box, though, or thwack any of them with her paws. She feeds them. Then the kittens grow into cats and the puppy grows into a pit bull and Lurlene gets her nipples back.

6.

My alley-neighbor, Jonathan, has a string of lights in his yard that loop from his detached garage, over the bistro table, and through the trees. He plugs them in when his daughter comes home from college. One night, when the lights were shining, I heard the clink of bottles and smelled a warming grill and heard him joke with his daughter about “little smokies.” Anytime I look out my back door and see glimmers between Jonathan’s oak leaves, I think a light-worthy someone must be over, and that feels safe to me, and a little special, the way I imagine it does to his guest. It’s a habit I’ve made since I can remember, assuming all the homes that are well lit, with shoveled walks in winter, and planted gardens in July, hold people who are well loved. It can’t be that simple, but it’s still a comforting thought. Under those trees and lights: a home. I wonder how different the world would be if every human knew that feeling.

Jennifer Eli Bowen from The Book Of Kin. Copyright © 2025 by Jennifer Eli Bowen. Reprinted with the permission of Milkweed Editions, milkweed.org.

Author photo: Emily Baxter