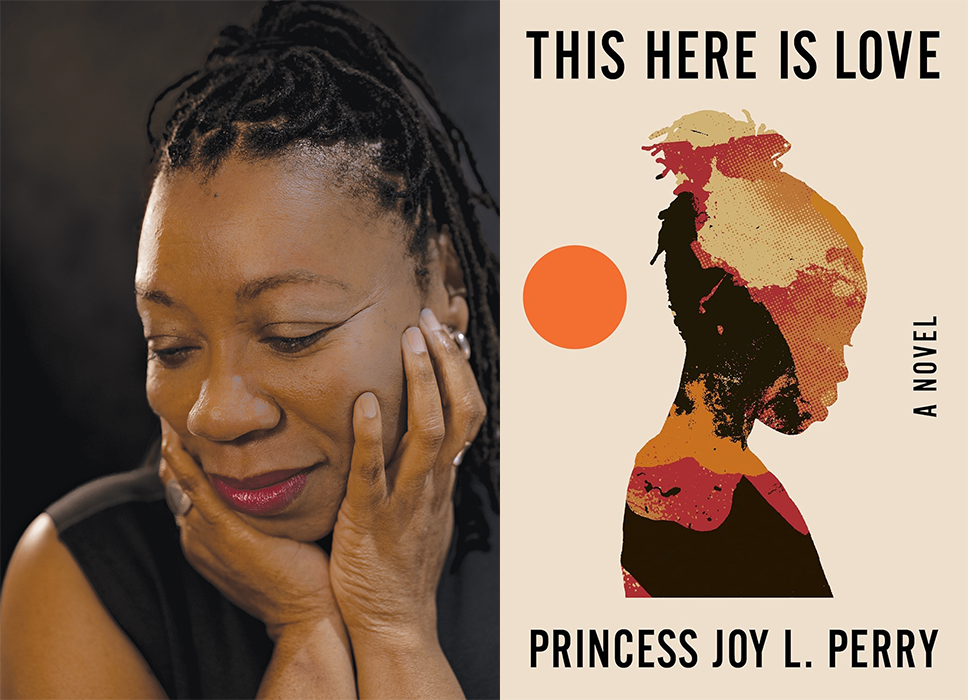

Princess Joy L. Perry

Age: 54. Residence: Norfolk, Virginia. Book: This Here Is Love (Norton, August 2025), a seventeenth-century tale of three characters, two enslaved and one indentured, whose intermingling stories challenge their understandings of freedom, familial ties, and love as they work to change their destinies. Agent: Victoria Sanders. Editor: Amy Cherry.

For almost two decades I have been a full-time lecturer of English at a local university. For most of those years that meant I was teaching over one hundred students every semester, each writing multiple composition papers and essays. Grading that amount of work took up my writing time and much of my cognitive energy. At the beginning of each semester, I’d tell myself I will get up with the sun to write, but there would always come a morning when I would sleep through my writing time—usually because I had been up the night before grading papers. I could never get back on schedule.

While I never became a writer who meets the muse at sunrise, I did become a writer who reads something beautiful, poetry or prose, for fifteen minutes in the morning and then writes for another ten or fifteen minutes. I write on the back of an envelope while I am waiting for the dentist to see me. I write on the Notes app of my phone when I go for a walk. Over the years, those fifteen minutes of hurried writing added up to a manuscript.

Next to finding time to write, the hardest part of creating my novel, This Here Is Love, was not giving up. Once I had an agent, there was still about a ten-year gap between signing with her and completing a book that could withstand the demands of the publishing world. My agent and her team were busy. They gave me feedback and let me work. They set no timetable, and no one called me up to say, “Hey, are you still working on that novel?” I had to keep at it on my own, of my own volition. I did that by participating in two writers groups. One group met regularly, once per month at our strongest. Another group met sporadically, a few times a year, when one of us needed feedback; we’d schedule a two- or three-day writing trip when our calendars aligned. These few committed people helped me to feel like a writer even when I had little tangible evidence in support of my dream.

And that is another thing: It is only now that I realize I was a real writer all along. I was regularly, over the course of many years, making time to put words on paper. I was researching. I was sacrificing family time and sunny days to get the story down. I was not a hobbyist, not a dabbler, not just a dreamer. I was a writer before a publishing company finally said yes to me. So are you.

Of my debut book, Library Journal wrote, “It’s hard to believe that this is Perry’s first novel, so effectively does it pull readers deep into the lives of its evolving, powerful, multifaceted characters.” Decades ago no one would have said that about my writing. This assessment is only possible because I evolved. I tapped into the power that comes with being a woman in my forties and now my fifties. I now know something that I can translate into words about grief and love and the workings of my own mind. Over time I grew into my ability to write.

So you are fifty years old or older. You have not gotten as far in your writing journey as you want to yet. That does not mean you won’t. You are writing. And you are reading this essay. That means something. If you were going to give up, you would have done it years ago. See it through. Now is your time.

An excerpt from This Here Is Love

Cassie’s Dance

The grown folks remembered their true homes, the taste of the rivers and the taste of the clay, the bluer sky and the closer moon. There, they would have danced in animal skins, in shirts of woven grass, in nothing but cowrie shells at the neck, wrists and ankles. In the colony of Virginia, they made do. On top of Negro cloth, they wore oyster and clam shells, the bones of rabbits and raccoons. They strung those bits and pieces on twine, on loops of dried grape vine, and tied them to ankle and knee, neck and hair. They turned all manner of clanging, whistling, noise making rubbish into treasure.

The people pooled their harvest rations with things nicked and pocketed while setting up a separate celebration for the white folks. So, there was some meat, goose and ham, a bit of liquor, nuts and yams. But more necessary than food was music.

Two men squatted on birthing stools, their knees spread wide to accommodate the drums, while the others gathered. Sincere, a slave who often played at the white folks fancy occasions, stepped from his cabin bearing his new fiddle like a scepter, though it was made of hollowed gourd and deer-hide with one string and a horsehair bow. To his wild plucking, there would be added a chorus of women, ululating to urge him on, and to that, the drums. The palm-beats would gallop from head to heart, head to heart, until everyone had been cajoled into joy.

Some wore masks, other danced barefaced. Sweat—clean as the waters of the Sassandra, the Anum, the Pendjari—washed away the false faces they wore all but a few days of the year. They kicked off hard, bulky shoes. They stood as if their backs never had been crooked by the endless swinging of a hoe, never bowed by bundles and barrels of tobacco hefted upon their heads. They transformed. They hopped and jumped and abandoned the daily effort to remain unseen. They erupted. An arched back. A whirling one-legged turn. Each body once again decided the bearing and intensity with which it needed to move.

When Cassie handed Bless her cup of dandelion wine to hold and spun into the clearing of firelight and drumbeat, and there, shut her eyes, Bless took one step forward, but in amazement, she faltered.

Odofoley! Odofoley! the other grown folks whooped. They clapped as Cassie dipped her torso and rippled her back. Her hip shakes were celebration, prayer and summons. She wanted and took more than joy from the dance. Odofoley danced things that only they, fellow marooned souls, could decipher and echo and answer with their throats and thighs and feet.

The captive-born children, like Bless, like Jeremiah, like Esther and all the others, could mimic the steps but could never follow them, not really, not back to the feeling where they began. And when the grown folks all died, as surely they must, this drum to body talk and everything it told or aimed to tell would die too. For the grown folks carried what their bondage-born children did not—a living memory of an unalterable self.

Excerpted from This Here Is Love: A Novel by Princess Joy L. Perry. Copyright © 2025 by Princess Joy L. Perry. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Author photo: Jennifer Natalie Fish