Lauren K. Watel

Age: 58. Residence: Decatur, Georgia. Book: Book of Potions (Sarabande Books, February 2025), a prose poetry collection offering a reflection on the self that captures dreamscapes, landscapes, and heartscapes, mysterious as much as it is fiercely forthright. Agent: None. Editor: Kristen Renee Miller.

For my entire adult life, going on forty years, I longed to have a book published. To that end I wrote novels, stories, poems, essays, what have yous. I tried over and over to get a book into the world with no success, while every writer I knew, and countless I didn’t know, managed the task perfectly well. What was wrong with me? I’d read widely, studied my craft, improved my work over decades. And yet my many book-length manuscripts sat in many dusty drawers.

To explain this failure to myself, I decided the publishing industry had singled me out for exclusion. I decided I was a pure artist, above the crass self-promotion of more successful writers. Because I’d devoted most of my energies to parenting, I deemed myself superior to the neglectful parents who had published books. Despite the skepticism of family and friends—surely, they reasoned, I had the skills to get a debut work accepted—I never wavered in these beliefs. The older I got, the more my lack of success outraged me, enraged me. I felt deeply ashamed. Frustrated. Bitter.

It wasn’t until my child grew up and left home that these narratives began to collapse under the weight of their own nonsense. Since the role of full-time parent no longer fit, I had to stop waiting for the pure artist to be discovered, stop avoiding self-promotion, stop making excuses, and step into the role of writer.

At fifty-four I took stock of my professional life, such as it was. My publishing record resembled that of your average emerging writer—someone, in my mind, much younger, fresh out of a creative writing program perhaps. Reassuring myself that a person can emerge at any age, I imagined becoming that hungry writer. How would I go about getting a book published?

To begin with, I had to try. Really try. Instead of sending out a few pieces here and there, willy-nilly, I needed to amass a lot of work and submit like crazy. I needed to submit smart—researching journals and editors and contests, finding the best fit for my work—rather than randomly. I needed to quit sulking and shaking my fist at the publishing world and learn to accept rejection as the price of participating in the process.

I also needed to separate the vocation of writing from the business of publishing. The best art requires of its maker an intense emotional investment, the courage to take risks, and the willingness to be vulnerable. One should write with abandon, with utter joy and desolation, probing one’s most tender parts, one’s darkest shames. But publication is another matter—practical, not spiritual. Here emotion and intensity only get in the way, as I knew all too well.

Most important, I had to grow up. I had to stop managing everyone else and learn, finally, how to manage myself. I had to tame my anxieties and cultivate my calm, my curiosity, my openness. I had to stop believing my self-justifying fairy tales and start believing in myself. Because even if I somehow managed to publish a book without growing up, I would still be a passive, delusional, reactive child, only now with a more respectable literary record.

I tell wonderful stories of how Book of Potions came to be: the life-changing call from my amazing publisher, the exciting editorial process, the creation of the gorgeous cover. But really it could have happened any number of ways. Why? Because I worked so hard to become a person who could get a book published. That work, the work of growing up, at least a little, turned out to be my greatest triumph.

An excerpt from Book of Potions

I Awoke on the Edge

I awoke on the edge of a field, a snow-covered meadow plated with sunlight, and the sky was bright white and unnatural, and the silence was white, too, a ravenous silence, and the birds had all gone away, and the squirrels were burrowed in the deep, and behind me the trees creaked in their bones, and the snow clung to their limbs, to their limbs down to the needles, the snow was layers thick and smooth, flawless across its surface like something spread by a machine, and sunlight skimmed over the snow as if it were an impenetrable metal, and I stepped onto the field holding my breath because I didn’t know how firm the snow was, or how deep, but it wasn’t the snow that gave with my every step, it was the silence, how I sank into it up to my knees, the silence crackling around my feet, pulling me down with a sharp gravity, and I slogged through the silence, my breath shrouding my face, and the silence sliced through my lips, through my throat and into my lungs, the silence swallowed up my chest, and how close it seemed, the other side, so I kept going, kept stepping across the snow-covered meadow, across the sunlight, across the glittering silence, which lit me up, me, who’d always bristled in silence, darkly.

The Jails

The jails, they’re full of prisoners. Why are they full of prisoners? Because everyone’s doing drugs or selling them. Why is everyone doing drugs or selling them? Because they’re bored and desperate. Why are they bored and desperate? Because they have no work. Why don’t they have work? Because the jobs went away. Why did the jobs go away? Because the bosses put in robots. Why did the bosses put in robots? Because robots don’t ask questions.

Why don’t robots ask questions? Because they don’t have minds. Why don’t they have minds? Because the scientists haven’t gotten that far. Why haven’t the scientists gotten that far? Because the government won’t fund them. Why won’t the government fund them? Because they’re funding the army. Why are they funding the army? So we can fight. Why should we fight? Because we have enemies. Why do we have enemies? Because we’re always interfering. Why are we interfering? Because we’re better than they are. Why are we better than they are? Because we’re free. Why are we free? Because we waged a war to worship our own gods. Why did we wage a war to worship our own gods? Because we felt oppressed. Why did we feel oppressed? Because they put us in the jails.

What Sounds

What sounds like silence is anger. Look, over there, it’s your father and grandfather and their fathers and grandfathers and so on, lining up, arms akimbo, across a field in a game of Red Rover, and they’re calling your name, calling you to come over. Is it a taunt? An invitation? Whatever it is, you’re off and running, like always, across the wild grasses, your breath puffing like smoke from a locomotive, the wind ripping through your hair. What’s happening to your hair? It’s turning brown again, your legs nimble and firm, pounding over the grasses, and your neck holding up your head like a sunflower’s stem, all your movements easy and painless, as if you’ve been released from gravity, and as you run, your fathers and grandfathers join hands. They tense their legs and set their faces, because they’re not letting you break through. This time they want to win.

Reprinted by permission of Sarabande Books, Inc. www.sarabandebooks.org. Source: Book of Potions (Sarabande Books, 2025).

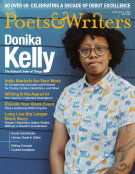

Author photo: Ashley Kauschinger