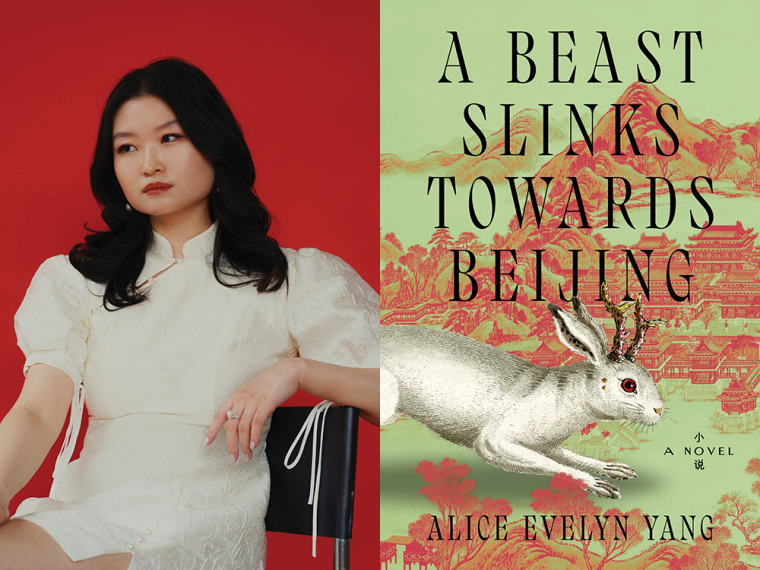

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Alice Evelyn Yang, whose debut novel, A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing, is out today from William Morrow. When her estranged father walks back into her life and explains he has a prophecy to deliver, Qianze worries that the aging man might be suffering from dementia or psychosis. For one thing, his recollections of childhood poverty in Japanese-occupied China are too old to be his own memories; his other tales mix historical events with supernatural encounters. But when long-suppressed family stories continue to spill out, a multigenerational account of colonial violence and its aftermath emerges. One ancestor observes that a female monster isn’t born but created, a human woman poisoned by a “putrid mixture of vengeance fury rage grief shame.” Publishers Weekly called A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing “a visionary debut,” while Thao Thai described the book as “a richly threaded novel” that “sings with artful prose and unforgettable storytelling, reminding us of the promise of redemption, even amid the dark consequences of violence.” Alice Evelyn Yang’s writing has been published in Apogee, The Rumpus, the Margins, and Michigan Quarterly Review, which awarded her its Jesmyn Ward Prize in 2023. She holds a BA in creative writing from Northwestern University and an MFA in fiction from Columbia University, where she received the Felipe P. De Alba Fellowship for excellence in first-year writing.

Alice Evelyn Yang, author of A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing. (Credit: Anna Letson)

1. How long did it take you to write A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing?

Two years to write my first draft in between my MFA courseload and my first full-time job as a designer at Tin House Books.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I recently found my New Year’s resolutions from 2012 stored in the archives of my Notes app. I was fourteen at the time, and one of my resolutions was to work towards was becoming a published author. I’ve known for a long time that I wanted to write a book, but the act of writing one was baffling. I had no idea how to do it. I went to graduate school to learn how, and still, I found myself bewildered with the sprawling mess of ideas I had before me. I had no clue how I was going to condense everything I wanted to say onto the page without telling too much or too little.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write at a small rolltop secretary’s desk I got from Facebook Marketplace out in Jersey—far enough away from the boroughs that the sellers couldn’t overcharge for it. It’s not very large, only about 30 inches wide, which is just enough for my laptop, a mouse, and a cup of coffee.

I read Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (Mariner Books, 2018) when I was in college and just starting my writing practice. Something that has stuck with me all this time was his chapter recalling his creative writing studies under Annie Dillard. He paraphrased one of her lessons, writing: “Writing is work [she had told us.] Anyone can do this, anyone can learn to do this. It’s not rocket science; it’s habits of mind and habits of work. I started with people much more talented than me, she said, and they’re dead or in jail or not writing. The difference between me and them is that I’m writing.”

Since reading this, I’ve been trying to create a daily writing practice, even if I’m only writing for a few moments. I write at night as I find my mind works better when it is dark and cool. (Summer is hard for my writing. Winter is where I flourish.) Sometimes, this looks like multi-hour writing sessions, and sometimes this looks like a sentence or two scribbled in my Notes app while slipping into sleep, suspended between waking and the unconscious.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’ve been reading books about and by anthropologists for my second book, which features a character working on her anthropology thesis. Some titles include Bog Queen (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2025) by Anna North, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human (University of California Press, 2013) by Eduardo Kohn, and the anthology Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), edited by Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I’ve recently seen a surge in interest in translated literature, but less so in translated literature from China. Authors like Mo Yan, Yan Lianke, and Ha Jin were fundamental to my writing of A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing, but I rarely find them talked about online.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Right now, I am struggling with discipline and attention. In just the few years since I wrote A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing, I feel like I’ve lost quite a bit of my ability to sit with uncomfortable tasks, like writing when I don’t want to or wading through a dense research text. For the most part, I blame the enmeshment of social media and instant gratification in our capitalist landscape. But I am trying to relearn how to do these slow, hard rituals and repair my relationship with discipline and attention.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I met my agent, Iwalani Kim, at an agent mixer thrown by my graduate school while I was still revising my very first draft of the novel. It was unpolished and had never been read before by a stranger—only a handful of close friends—but I sent her my first hundred pages. She read it in one night. That was her first demonstration of her belief in me, and I carried that faith through revision, submission, editing, and to the present, and I plan to do so for a long time yet.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing, what would you say?

One day, all that sacrifice will have been worth it.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing?

Consuming all forms of art widely and indiscriminately. Sometimes this entailed a walk around the reservoir of Central Park while on the phone with my father, and sometimes this was explicit consumption, like visiting a museum or attending a theatrical experience. During this time, I threw myself back into 35mm film photography, as I found the waiting for my developed photos a good exercise in slow gratification, which was useful while writing a book. Similarly, in periods of burn out, I returned to slow acts of crafting: crochet, embroidery, jewelry making.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“No one ever reads a book and thinks, ‘Wow, I wish that author had spent less time on this.’” My friend and fellow author told me this while I was pushing up against my self-imposed deadlines during drafting and revision. I was burnt out, impatient, and ramming myself into a blank document, and all I wanted was to finish the book and then to have it out of my hands and into the world. That advice made me slow down and allow myself rest. In order to do justice to the original idea of the novel and the writer who had begun it, I had to linger and give the writing the time it needed.