This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Ellen Cooney, whose latest novel, One Night Two Souls Went Walking, is out today from Coffee House Press. The unnamed narrator of One Night Two Souls Went Walking has always ruminated on existential questions. She recalls asking her parents at an early age, “What is a soul?” Now in her mid-thirties, attending patients as an interfaith chaplain at a local hospital, she contemplates the same question, turning it over and over and finding new angles. Accompanied by a dog who might well be a ghost, she makes the rounds on the night shift, uncovering new truths about her patients and herself in the process. “This book will grab your heart and not let go,” writes John Grogan. Ellen Cooney is the author of nine previous novels, including The Mountaintop School for Dogs and Other Second Chances (Mariner Books, 2015) and Lambrusco (Pantheon, 2009). Her stories have also appeared in the New Yorker, Ontario Review, and New England Review, among other publications. Born in Massachusetts, she lives on the Phippsburg Peninsula in Maine.

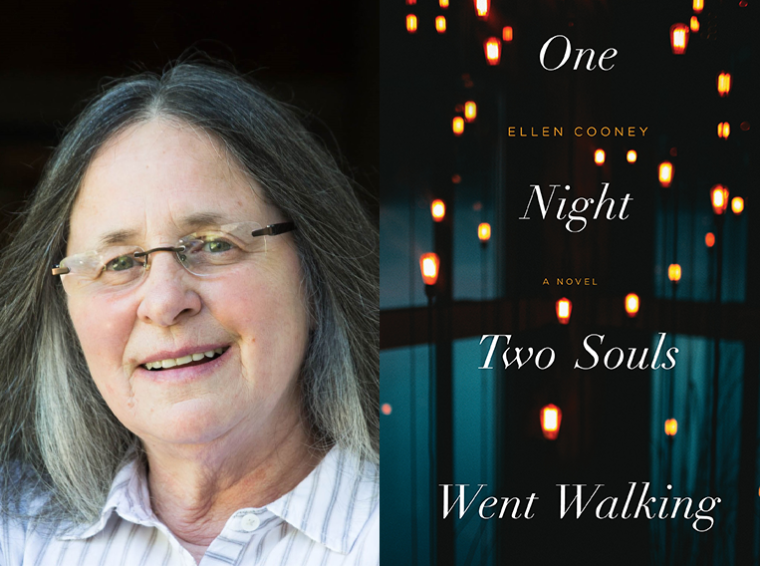

Ellen Cooney, author of One Night Two Souls Went Walking. (Credit: Greta Rybus)

1. How long did it take you to write One Night Two Souls Went Walking?

I think about four years. Of actual writing, I mean. There were lots of drafts, each wildly different. It was such a long time coming. I’d had the main character in mind for ages, also the idea of a novel in some sort of medical setting. Why? I was the daughter of a nurse. In my teenhood I worked in our local hospital. As a mom I was in and out of hospitals all the time with my special-needs child. I’m a very ordinary fiction writer in that everything in my life is material. It’s mostly an issue of when to use what, and how. Which can take ages to become known to you!

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

The earliest are many and all about flying, or at least being up in the air and sort of floating around, looking at people and stuff below: memory fragments and vivid scenes involving a small me and that powerful, terrible desire to be like a bird or human kite. Terrible because you have to get it in your head that it’s a desire that will never come true. But then, for me, I was so lucky. I was a child poet. And also a playwright and a story writer.

Writing is like flying. Well, kind of. My personal greatest fortune is that I know how it feels when a paragraph or a sentence, after many, many tries in the creation, comes out right. Absolutely that’s a desire fulfilled.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Not losing my nerve. The form is a tricky one that needed to look so simple; it all just sort of happened. Also, not settling for a draft that was good, merely good, when it nagged at me that I could make it better, even take it to another level.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I only write in my writing room, which is small, and except for bookshelves, blank on the walls. Every day I come in here and write, and either it gets thrown out immediately, or saved for future deletion, until something starts working and a novel is happening. I try to keep a routine about it. Failure all the time! Once I get near what might be the end of the first draft, I have to be reminded to eat and sleep and like, show signs I am a normal functioning human being.

5. What are you reading right now?

I always have a thing going on with some Italian poet from another age, which is my way of staying the grandchild of Italian immigrants—a part of me is always in their other-country of a home, with another language filling the air, always as poetry, even when members of my family were screaming insults or threatening to cause great harm to each other. “My” poet right now is Giuseppe Ungaretti. I am going through a dual-language edition from Archipelago Books of Allegria.

Never, though, am I reading just one thing. For stories I’m in and out of three collections, in daytime only, as these are works that delight me but also in different ways baffle me, scare me, and freak me out: The Lonesome Bodybuilder by Yukiko Motoya, Wild Milk by Sabrina Orah Mark, and Song for the Unraveling of the World by Brian Evenson. For evening reading I just started the novel River by Esther Kinsky, and I’m slowly absorbing the poetry-like Annotations by John Keene.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I don’t think I’m sure what “wider recognition” means. But like lots of people, especially old-time English majors and getters of graduate degrees in lit, I think about the thing called “the canon,” especially, lately, in terms of American works and writers. You can think, for example, you know something about fiction of the first quarter of the twentieth century, and then one day in a used bookstore you happen upon a Dover Thrift Edition of something called American Indian Stories and Old Indian Legends by someone called Zitkala-Sa, and how come you didn’t know about these pieces? I do not think you can just blame yourself for not knowing such a thing before.

7. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Impediments change from life phase to life phase. For me right now it’s all about energy and physical stresses, as I was very ill for a couple of months and while I’m fine now, more or less, I have to learn to live and work—which often mean the same thing—with limitations. I hate it that I can’t go strongly through a long writing shift, and I have to take naps like a toddler. But! I’m still around and still writing!

8. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of One Night Two Souls Went Walking?

Two of my favorite stories are by Gabriel García Márquez: “Eyes of a Blue Dog” and “A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings.” In my novel there are no obvious indications of either work. Because isn’t that the best thing about inspirations? You steal and conceal.

Somewhere around Draft Number Eight, I realized that an element of each of those stories made it in, morphed of course into my own way of doing things. I was reminded of that angel and those dreamers in my own prose. I loved the surprise of that.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I’ve had the same three first readers for ages and ages, and apart from them, I do not show manuscripts to anyone outside the publishing process. Of those three—son, wife, dearest old friend—the number one is my son. I was a teen mom, and for a long time it was just him and me. Which is to say, we go back. He is fifty. I’ve been reading to him his whole life. Lately, since we live on different coasts, him west and me east, we’re on the phone or videos. I read him the rawest, most vulnerable-making early drafts. He never has to use words to tell me when something is off or way less good than I could make it. He can grunt a certain way. Or breathe. Or make a face that’s sort of, “Meh.” Although he is not above outright letting me know something like, “The description of the guy in the next-to-last paragraph kind of sucks, Mom.”

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I really heard this, because it came from myself: a rule, from a time when I needed it, laid out by the me of that present to the me of any future. “Do not write in your head.”

Somewhere in some anthology or collection of stories by Patricia Highsmith, there’s one about a fiction writer, writing fiction. Really actually writing. Punctuation and everything. The reader becomes a peeper, a spy on a creative act, and it’s thrilling and very intimate, and then whap, you find out the writer was imagining the writing, was doing the piece without writing it down, and whap again, the piece will never actually exist. Please if anyone knows what this story is or where it is, do not tell me; I never want to see it again. It’s too horrifying. I know exactly how it feels to sit down to write something I had planned out in my head—when finally in my day, or more likely my night, I had time to work—and nothing came, because I already wrote it.