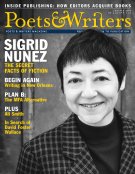

In the past eleven years, Sigrid Nunez has written five novels, all of which are subtle investigations of how one’s identity is forged in that space between what is known, or can be known, and what is withheld. It’s a fitting project for a novelist whose name simultaneously reveals and conceals her background. Her name hints at a dual heritage—she is the daughter of a German mother and part-Panamanian father—but it doesn’t reflect her father’s Chinese roots nor the Eastern culture that plays such an important role in her life. In her most recent novel, The Last of Her Kind, forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux this month, Nunez continues her exploration of identity through the characters of Dooley Ann Drayton and Georgette George, two young women who meet as roommates at Barnard College in 1968, to form a relationship that Nunez calls “a kind of temporary arranged marriage.”

With the assertion that there are “no innocent white people,” Ann rejects her privileged upbringing in Connecticut, starting with her given name, Dooley, which she sees as a “shameful” reminder that her family is descended from Southern plantation owners. She believes in complete openness as both personal credo and political ideology. She says, “In a truly enlightened and just society there would be no secrets.” The more sheltered Georgette—the first of her working class family to attend college—struggles with feeling like an outsider. She arms herself with a motto, “Don’t let the pack know you’re wounded,” which helps her resist her instinct “to wound or kill any one of that number…who made me feel helpless, humiliated, afraid.” Ann reveals; Georgette conceals. Or so it seems.

The Last of Her Kind, which was chosen as an alternate selection for the Book of the Month Club, and has received strong reviews prior to its publication, traces the unlikely and uneasy friendship of these two women—one committed to radical social change, the other choosing a more conventional life—in the late ’60s, the years marked by the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, Woodstock, the Black Panthers, and the infamous Rolling Stones performance at Altamont. Using this tumultuous time as a backdrop, Nunez confronts big questions of moral complexity, the arrogant underside of idealism, the shifting line between principles and fanaticism, and America’s fascination with violence. The Last of Her Kind focuses not only on the kind of violence unleashed by a declaration of war, or fired from the barrel of a gun, but also on the more intimate violence of suppressed anger and missed opportunities between husbands and wives, parents and children, friends and lovers.

![]()

Nunez has been winning literary prizes and enjoying prestigious teaching appointments for years with surprisingly little fanfare. The recipient of a Whiting Writer’s Award and a residency from the Lannan Foundation, she was the Rome Prize Fellow in Literature at the American Academy in Rome from 2000 to 2001. In 2003, she was elected a Literature Fellow by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and last spring she won a fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin. She has taught at Amherst College, Smith College, and Columbia University. She has also been on the faculty of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and serves as a mentor at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. Nunez is currently teaching in the graduate writing program at the New School in Manhattan. Starting this spring, she will be a visiting writer at Washington University in St. Louis.

While her responsibilities as a teacher keep her busy, Nunez says she finds time to write every day. “It’s not such a difficult balance for me because I only teach part-time, I don’t have a family, and I live by myself. I want to be writing all the time,” she says. “Even as a little kid, I wanted to be a writer. I thought I’d grow up to be a children’s book writer. I wanted to be Dr. Seuss. So, every job I’ve ever had has been to support my writing habit.”

Her list of honors, awards, and teaching gigs is impressive by any writer’s standards, but it’s especially so for one who grew up in a household where neither parent was entirely comfortable with English—neither spoke the other’s language, and neither the father nor the mother tried to teach their daughter his or her native Chinese or German, an omission Nunez has described as “a terrible withholding.” But it was English—her perfectly spoken, beautifully written English—that she used in 1968 as her passport to Barnard College in Manhattan, a place that might as well have been a continent away from the projects on Staten Island where she grew up in the 1950s.

Nunez chronicled her childhood and adolescence in her first book, A Feather on the Breath of God, which was originally published by HarperCollins in 1995, and was recently reissued in paperback by Picador. Although technically a novel, it resembles a memoir, with telltale signs that the material is made up of nonfiction as well as fiction. Nunez calls it “my real hybrid genre book. Even though there are parts that are based on my parents, with little distance between author and narrative, it isn’t really a memoir, because there’s a sufficient amount of distortion and invention.”

A Feather on the Breath of God fits her description of the hybrid, which she says combines elements from more than one genre to form a book that is “part novel, part history, part journal, part travel book, part essay.” In this case, Nunez fuses fiction with autobiographical details. Thus, her depiction of her parents’ backgrounds is, she says, “totally accurate.”

Whether it’s the truth of fact or memory or imagination, what is most striking is the book’s depiction of silence in an impoverished household, where the German war bride wishes for blond-haired, blue-eyed children and the Chinese Panamanian father remains mute, possibly, the narrator finally realizes, “not as one who would not speak but as one to whom no one would listen.”

A Feather on the Breath of God met with both critical and commercial success. Reviewers called it “beautifully honed” and “haunting and alluring,” with a “tone-poem-like quality.” Parts of it have appeared in anthologies of Asian-American literature; it was a finalist for both the PEN/Hemingway Award for First Fiction and the Barnes & Noble Discover New Writers Award. And it received the Asian American Studies Award for best novel of the year. Nunez doubts that many would classify her as an Asian American writer, and she recognizes that there is some measure of peculiarity in her winning this award. However, she points out that it was given for specific portions of the book, “especially the part called ‘Chang,’ about my half-Chinese father and his identity as a Chinese American,” she says. “This is one aspect of my life and my life as a writer, so it makes sense to me for it to be recognized as part of that [Asian American] literature.”