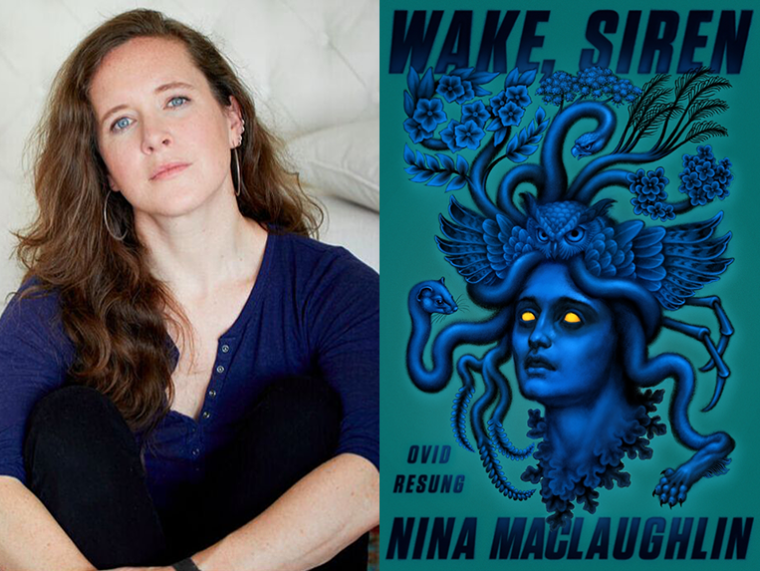

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Nina MacLaughlin, whose second book, Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung, is out today from FSG Originals. In Wake, Siren, MacLaughlin inhabits the voices of nearly every female figure from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, retelling the many myths of the epic poem from their perspectives. Across chapters of varied structure and style, the women are newly in conversation with one another, enriching and complicating Ovid’s record. The same questions have endured across the centuries: “How can we make sense of change? What to do about the ends?” writes MacLaughlin. In Wake, Siren, simple answers remain elusive, but these perennial questions become more capacious—conscious of their edges, silences, and exclusions—and MacLaughlin lays bare the violence once glossed over and long distorted. “Savage, cheeky, incisively aware of the social-domestic-economic-political thorninesses that prick (and mortally or immortally wound) interactions between power unequals, MacLaughlin opens a pressure valve that’s been sealed shut for centuries,” writes Heidi Julavits. Nina MacLaughlin is also the author of a memoir, Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter. Her writing has appeared in various outlets including the Paris Review Daily, the Believer, American Short Fiction, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and the Boston Globe, where she serves as a books columnist. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Nina MacLaughlin, author of Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung. (Credit: Kelly Davidson)

1. How long did it take you to write Wake, Siren?

It took a little less than three months. It happened very fast. I have tried hard to figure out the precise alchemy that allowed for this altered kind of outpouring, and I hope to be able to replicate it in the future, but my sense is it might’ve been a one-time miracle. For perspective, my first book, Hammer Head, took over three years and I rewrote it, I don’t know, maybe seven times. I don’t know exactly how Wake, Siren happened, but it is a mystery I am so, so grateful for.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

When I finished, I did a spell check and sent it to my agent. I hadn’t told her, or anyone, I was working on it, and I didn’t read it over before I handed it off to her. The book sold and then I had to read it over. That initial round of edits, last winter, reading it over for the first time, was a bizarre and challenging experience. Much of the book I had no recollection of writing, and it was strange to be confronted with what I’d done, as though I was getting access to parts of my mind I hadn’t known existed along with the repeated sense, I wrote this? It was jarring and it was hugely uncomfortable.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Mostly I work in my apartment, sometimes on the couch, sometimes on my bed, sometimes at my actual desk, occasionally at the kitchen counter. My best hours for putting sentences together are the early ones. The fullest writing days run from about 6:45 AM to 1:30 PM. My idea-brain sometimes gets cooking after 8:00 PM, but for actual words on paper, morning is best. When I’m deep in a project, I write every day, even just a paragraph or two on an “off” day. I like to be in daily touch with it. When I’m less deep in a project, I still write most days. Like running, there are times when you do not want to haul your ass out of doors and run, but you never regret it afterwards. The 1,500 words I wrote yesterday about a sheepskin rug, they’re useless and will go nowhere, but it was better than not doing it at all. And, like running, at the end of an otherwise empty day, it’s possible to say, well, at least I did that.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished The Rings of Saturn by W. G. Sebald. I’d tried it three times before and it never held me. A friend told me it’s a book for when you have six hours on a train and nothing else to do but read and look out the window. I was in a situation that approximated that and tore through it. I’m making my slow way through The Poetics of Reverie by Gaston Bachelard, which is an exploration of dreams and dreaminess and the poetic impulse. Some of it is ridiculous, but I like Bachelard’s enthusiasm and wild mind. I’m reading the intimate, potent Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lorde for my small and powerful book club. And before bed I’ve been dipping back into John Berger’s mini-bios of artists in Portraits.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I encountered the work of two poets this year which I’ve been talking about to anyone who will listen. The Chilean poet Raúl Zurita and the Danish poet Inger Christensen. They are widely recognized, and it speaks to my limits as a reader that I was so late coming to them. But I still want everyone to know.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Without question, the internet.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I was talking with my editor about the natural sorts of nerves that arise in advance of a book coming out, one of which is the revealing that I have this perverse weird imagination. My editor shrugged, “Not that weird,” she said. This was both deeply comforting, and also motivating, as in, there’s space to get weirder.

8. What is the one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

To have more people of color as editors and literary gatekeepers.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My young brother Sam doesn’t give many compliments. And he’s almost always the first, and often the only person I show work-in-progress to. His ear and eye for precision is unmatched, and he has a poet’s sense of the risks that are—and are not—worth taking with language. Part of the benefit of sharing DNA is that he knows me well enough to have a sense of what I’m trying to do, even if I’m not quite getting there, and, like the best sorts of editors, can push in the right direction. I know I won’t get empty praise, and I will get thoughtful suggestions and places to improve, and the arguments about commas end in laughs.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The best writing advice happens also to be the best life advice: Stay open. Pay attention. And whenever I sit down to start writing something, I repeat the words that the editor S.I. Rosenbaum told me years ago as I was working on a piece for her: “Tilt for the cliff,” she said. “Tilt for the cliff,” I tell myself as I start every piece, or when I feel things getting flat or safe. “Tilt for the cliff.” The words work like a spell and electrify body and brain both. Push, push harder.