This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Elaine Equi, whose poetry collection The Intangibles is out today from Coffee House Press. Concerned by the encroaching rule of algorithms, Equi resists with dynamic verse: “A poet is someone who goes out of her way to preserve / a mystery.” With incisive wit, she urges readers away from the “rectangular forest” of screens and models more daring pursuits. She imagines herself as a bouncer; she writes a love poem to her husband; she wonders at the nature of time—how is it possible that she’s been teaching for nearly forty years? Across these varied subjects, Equi always revels in the strangeness of her thoughts and emotions—her world, in all its detail, is sharply observed, but never pinned down. “She trims a narrative to its mad essence,” writes Wayne Koestenbaum of The Intangibles. “She winnows lyric into a shape more giddy than aphorism, more delirious than koan.” Elaine Equi is the author of more than ten poetry collections, including her debut, Federal Woman (Danaides Press, 1978), and Ripple Effect: New and Selected Poems (Coffee House Press, 2007), which was a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize and shortlisted for the International Griffin Poetry Prize. Her poems have also appeared in various publications such as the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and Best American Poetry. Born in Oak Park, Illinois, Equi lives in New York City. She teaches at New York University and in the MFA program at the New School.

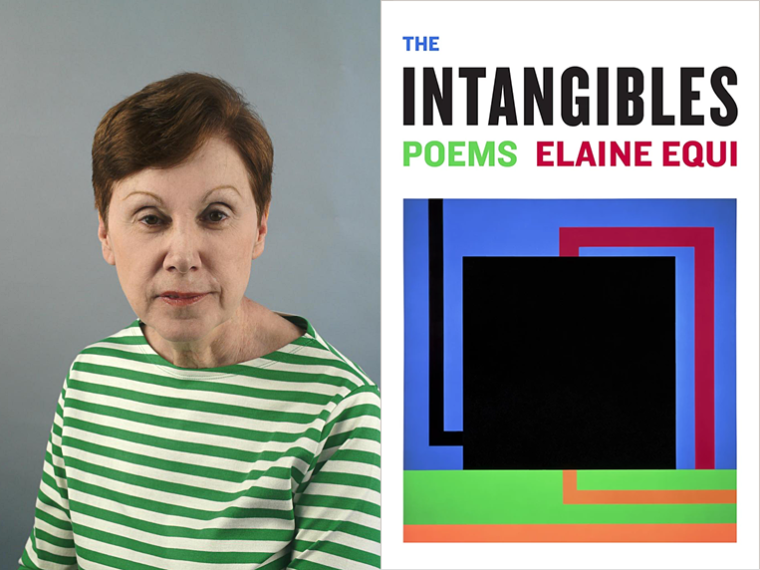

Elaine Equi, author of The Intangibles. (Credit: Becket Logan)

1. How long did it take you to write The Intangibles?

It took about four years. It’s ninety-six pages long, so that comes to about two pages per month. I usually write more than that, but a lot gets thrown away.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

About three-quarters of the way through the book, there was a fire in my apartment building. I was home at the time and one of the few things I grabbed before running out to the street was the manuscript. Luckily, no one was hurt, but it was incredibly disruptive. I had to put everything in storage and wasn’t able to return to my place for a whole year while repairs were being done. I finished the first draft of the book while sitting in a hotel lounge drinking iced tea. I was glad to have a project to focus on that made me feel more in control. I didn’t write about the fire directly, but the whole experience took me out of my comfort zone in what was ultimately a good way. Rather than knowing exactly how the book should unfold, organizing it became a way for me to respond creatively to the unexpected.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I used to like to write late at night, but now I much prefer the morning. And I almost always write at home. I have a big stack of notebooks and books piled up around my chair. I probably write something almost every day even if it’s just a few lines. Sometimes I keep a dream journal, which is a good way to ease into a poem. In the future, I’d like to try writing more outside, preferably someplace beautiful.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Dunce by Mary Ruefle and really enjoyed it. Her poems are wonderfully wayward and weird—but not in a random way. I didn’t even want to wait for the paperback. I know I really like a poet when I have to get the hardcover.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

That is a very long list, but I’ll start with Paul Violi. I had the pleasure of working with him at the New School in New York before he died in 2011. His poems are so witty and inventive. He’s written poems in the form of an index, a police blotter, a quiz. I’m glad there’s a nice edition of his selected poems still available. There are many poets I love who were mainly published by small presses, and after they die, their books often vanish. I wish more of those collections could be archived and republished as e-books.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I teach in an MFA program and think they are useful. If you have the time, money, and inclination, an MFA is a great way to focus intensively on your work. But there are definitely other ways to nurture and develop your writing. There are a lot of exciting literary and arts centers all over the country that offer workshops, lectures, readings, and events where you can connect with other writers. Plus, you can usually find terrific writing and literature classes in the continuing education departments of most universities.

7. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

My nerves. I’m a moody person and sometimes I just can’t access the clarity and objectivity—the equanimity—I need in order to write. I have a line in one piece that says: “My poem that still suffers in the twenty-first century from neurasthenia.” Life often moves too fast for me.

8. What is the one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I’m as ambitious as the next person, but I think too much emphasis is placed on contests and prizes. It makes me sad that a young poet looking to publish a first book will probably be entering a lot of contests. I do realize contests help fund small presses, but they shouldn’t be the only or even the predominant path to publication.

9. Who is the most trusted reader of your work and why?

My husband, Jerome Sala. He’s an amazing poet, but he also worked for many years as a copywriter and creative director in advertising. He can edit anything.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Don’t be afraid to cut it if it’s not working.