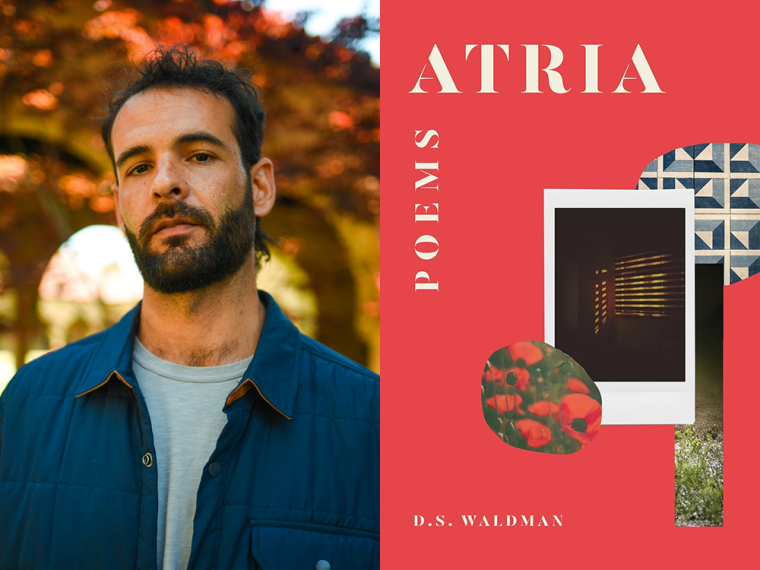

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features D. S. Waldman, whose debut poetry collection, Atria, is out today from Liveright. Throughout the collection, Waldman investigates the eloquent possibilities of restraint and silence, observing, “No coincidence that brevity rhymes / And relishes the curl at line’s end.” Moments of revelatory quiet can be found in encounters with art: A Polaroid of the poet’s mother shows her transfixed before a white square in a Julie Mehretu painting, her own white hair “in conversation with a patch of glare.” In “Low Poetics,” Waldman considers the imaginative engagement demanded by fragmentation, including the “little puzzles” of a disability that leaves him without an obvious dominant hand. Across forms and in conversation with both artistic and intimate interlocutors—lover, family, therapist, friends—the poet finds, “All language left in the air, without a response, starts to sound crazy, or like poetry.” Aracelis Girmay praised the collection as “an understated, exquisite work of intellect and lucid attention.” Richard Siken wrote, “D. S. Waldman explores the architectures of dream and poem with the eye of a Cubist: constructing a poetry that moves between theory and reverie, between textured music and frank retelling.” D. S. Waldman’s poems have appeared in the Atlantic, Boston Review, the New Yorker, and other publications. From 2022 to 2024, he held a Wallace Stegner Fellowship; he now teaches at Brooklyn Poets and Poets House. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

D. S. Waldman, author of Atria. (Credit: Jemimah Wei)

1. How long did it take you to write Atria?

In one sense, it really didn’t take that long. I wrote the first poem, “A Love Poem,” in the summer of 2022, and I wrote the final poem, “The Lake,” in April 2024. Not even two years. But the more truthful answer is that I began writing poems in 2017, and over a five year span I wrote, revised, and ultimately trashed two full manuscripts. So even though this is the first book I will have published, it’s the third I’ve written. And all of that was necessary to get to Atria. So I think my honest answer is seven years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Getting out of the way. While I was writing these poems, I envisioned so many final forms for them to take, collectively. In a manuscript, I mean. At first, I thought it would be this art criticism poetry thing without any sense of the elegiac—because I thought the elegies wanted to be their own book. But the more I showed the manuscript to friends, the more emphatically they told me it all wanted to be together, the elegies, the art stuff, the love poems. They needed to work in concert and inflect each other. The more types of poems I let into the book—the more completely I got out of the way—the more interesting, and I think authentic, it became.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m someone who needs to get to the page every day. Keeping an oar in the water, an old friend called it. I think of it almost like practicing scales, in music, or in visual art it might be like sketching. Just a way to stay in the medium, practice, try out some things. What that means, of course, is that I end up throwing away most of what I write, or at least most of what I write remains private, and that’s something I just have to be OK with. It’s hard when life gets busy and every moment spent writing feels valuable and hard to come by—hard to throw things away, I mean, to not have each word or line or sentence equate to progress, movement toward some finished, material thing, a poem, a story, an essay. But it’s so easy for me to fall out of language. If I’m away from the page for an extended stretch, it takes so much time and energy to figure it all out again, to figure out who I am in writing.

4. What are you reading right now?

Anything I enjoy I have to read at least two or three times. So I’m on my third pass of Patricia Lockwood’s Will There Ever Be Another You (Riverhead Books, 2025). And I just finished my second read of Maggie Nelson’s essay The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift (Graywolf Press, 2025). I love reading things in pairs or trios, and there is something exciting about this particular Lockwood-Nelson duet. I recommend!

5. Which poet, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Frank X Walker. Growing up in Kentucky, he was the first poet I’d ever heard of, and definitely the first I’d ever read or seen read. He cofounded the Affrilachian Poets movement, and I believe coined the word Affrilachian. He’s mentored so many poets coming out of Kentucky. Poetry magazine just did a beautiful folio of his work, and I was so glad to see that. I’m honored to now be a press-mate of his.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I quite enjoy organizing poetry manuscripts. I spent a lot of time, while I finished the book, listening to The Köln Concert—there’s a poem in the book called “The Köln Concert,” and at least one other that references it. Part of what I love about that concert is the surprising tonal shifts between movements. Keith Jarrett will have you feeling super melancholy and slow, like a cold rainy day in the city, and somehow over a span of maybe ten seconds he’ll have you charging toward a spring day with cherry blossoms and café chatter and new love. I wanted the book to move that way, surprising but still fluid. I wanted to spread each of these disparate threads out across the book and overlay them in a way that felt, somehow, compositionally satisfying, for poems to flow into each other tonally rather than according to some sort of content-specific continuity.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

I wrote the first poem in the book, “Calder,” at SFMoMA, in a room full of Calder’s mobiles. The poem ends basically with this young kid running into the room and slapping one of the mobiles. I will forever associate that wild and funny and surprising moment with this book, as if that slap was the spark that let me know there was a book here.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Atria, what would you say?

Take your time. As I mentioned earlier, I wrote the poems in this book pretty quickly, in less than two years. And even within that flurry, I still had moments where I prematurely thought the book was done—can you imagine that? Writing poems for a year and thinking you have a collection. It was delusional. And I’m grateful I had friends and a mentor, Louise Glück, who brought me back to reality, who said I have interesting poems, and that I need to keep writing.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Atria?

While writing the poems for Atria I also wrote a draft of my first novel. It was my first time writing fiction, and I loved how, for me anyway, writing something longform like that took so much pressure off my poems. I didn’t have to be writing or even thinking about poems every day. I could be writing just prose for a stretch of weeks between poems, then out of nowhere a poem arrives and asks to be written. I think some of my favorite poems in the book happened that way, and generally my poetry was much improved, I think, because I had this other outlet for my writing itch; the prose stream was always running, so the poems could appear when they were ready.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Louise Glück, after reading a few poems of mine that were not so great, told me she thought I was someone who really needed to take my time. This is a life’s work, she told me, if you’re lucky enough to have a long life, you will need all of it to write the poems you need to write. Basically all my close mentors have said something along these lines. Amaud Jamaal Johnson, who I really trust and admire, said once that even the very best of us poets are remembered for only a few poems, maybe one truly outstanding book. And it’s true! How many of Elizabeth Bishop’s poems can you name off-hand? His point, similar to Louise’s, was that every poem is an opportunity to pin one’s voice to eternity. And that sort of thing takes time.