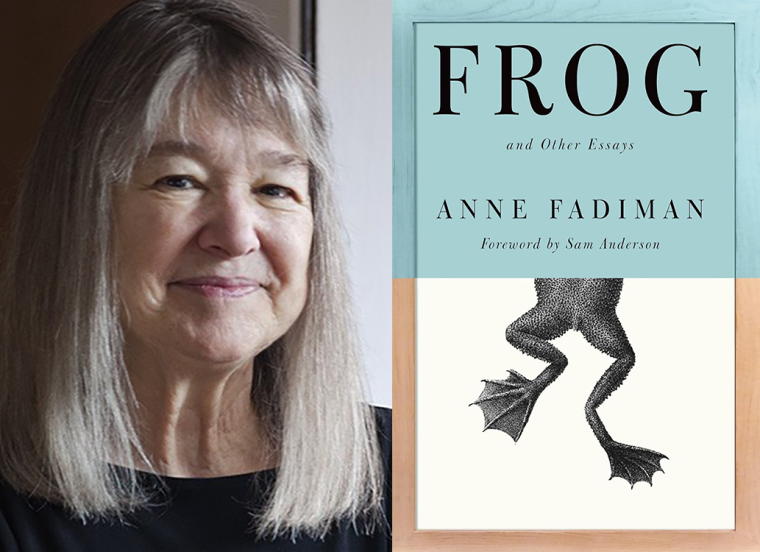

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Anne Fadiman, whose essay collection Frog: And Other Essays is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Fadiman sets a tone of wry humor and sharp-eyed sympathy in the collection’s titular essay, which opens on the image of a dead pet frog stashed in a freezer, “flat and compact and, very soon, as rigid as a cell phone.” Later, reflecting on the frog’s surprisingly long and unexamined life alone in a small tank, the author wonders: “Is it enough to shelter, feed, and bury an animal, to keep it alive for sixteen years, or maybe seventeen, and never understand the first thing about it?” The essays that follow span a requiem for Fadiman’s Hewlett-Packard LaserJet Series II printer, a reconsideration of the overshadowed life of poet Hartley Coleridge, and the history of the South Polar Times, Antarctica’s only magazine. Publishers Weekly noted that Fadiman “has a knack for finding the extraordinary in the ordinary, using everyday objects to explore such profound themes as grief, loss, and personal growth.” Michael Cunningham, meanwhile, praised Frog: And Other Essays as “humane, penetrating, and gorgeously wrought.” Anne Fadiman’s first book, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997), won the National Book Critics Circle Award for General Nonfiction, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the Salon Book Award. Her other titles include two essay collections, Ex Libris (1998) and At Large and At Small (2007), and the memoir The Wine Lover’s Daughter (2017), all published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Formerly the editor of The American Scholar, she now teaches at Yale University, where she is the Francis Writer in Residence.

Anne Fadiman, author of Frog: And Other Essays. (Credit: Gabriel Amadeus Cooney)

1. How long did it take you to write Frog: And Other Essays?

Bits and pieces of fourteen years, with a lot of revision at the end.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The title essay was uncomfortable to write because I was ashamed of my failure to provide our family’s pet frog, Bunky, with an adequate aquarium. This sounds trivial, but I’m still ashamed, and I dreaded outing myself as someone who professed to be a friend of animals but treated one badly.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Mostly in a rented one-room cabin without internet, cell service, land line, or hot water. Mostly summers, because I’m a teacher. Much of it late at night.

4. What are you reading right now?

Books by and about M. F. K. Fisher, to prepare for writing an introduction to Consider the Oyster.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

The early books of the environmental writer Kenneth Brower. I remember reading The Starship and the Canoe—a wildly idiosyncratic double portrait of an astrophysicist and his kayak-builder son—when it came out in 1978, before I’d heard the term “creative nonfiction,” and thinking, “Whoa, you can do that with a profile?”

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Teaching, because it swallows up such a large fraction of every year. But it’s also the biggest boon. Smart college students provide indispensable stimulation. Writing is such a solitary enterprise that it’s all too easy to become walled off from the world, especially as you get older. My students pry my world open.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Not the earliest, but perhaps the most important: In 2019, I was invited to lunch on the Upper West Side with Rick MacArthur, the publisher of Harper’s, and Ellen Rosenbush, the editor at the time. I’d been taken to lunch by editors only a handful of times, and this restaurant was extra swanky. I pitched five essays. I ended up writing two of them, one on pronouns and one on my family’s deceased frog. I knew pronouns would be a big undertaking, but I thought I could knock off the frog essay in three or four pages. Ha. If it hadn’t been for that lunch, this book might not exist.

8. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When I sent him this book, my editor, Jonathan Galassi, whom I’ve known since I was twenty, wrote me an e-mail describing it as “crypto-autobiographical.” What he meant was that even the essays that weren’t ostensibly about me—for instance, the ones about Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s relationship with his son Hartley, or about the South Polar Times, a periodical published (in an edition of one) during Robert Falcon Scott’s Antarctic expeditions—were so deeply imprinted with my interests and temperament that they actually were about me. This made me feel both problematically egotistical (would the reader have no escape from me?) and secretly relieved (the collection wasn’t as miscellaneous as I’d feared).

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Frog: And Other Essays?

See Question 6. But if you mean what kinds of work aside from making sentences: Research. Not for the purely personal essays, but for the ones on pronouns, the Coleridges, and the South Polar Times. Articles, books, letters, journals.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“I only write what only I can write.” My husband, the writer George Howe Colt, shared this quote with me many years ago. He’d heard it was by Isaac Bashevis Singer, but neither of us has been able to track it down definitively. (If any P&W readers can help, let me know!) It’s not just what you write about, it’s how you write it—what attitude and style you bring to the work. If someone else could do it better, don’t write it.