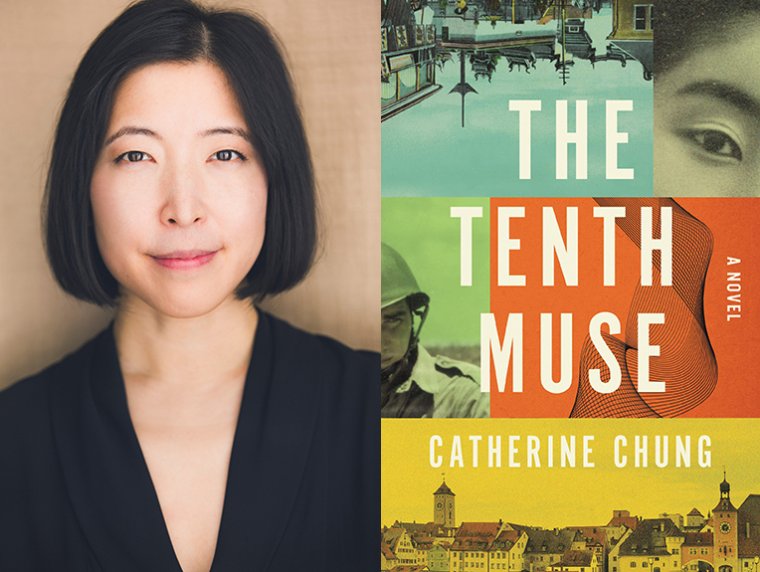

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Catherine Chung, whose second novel, The Tenth Muse, is out today from Ecco. Growing up with a Chinese mother (who eventually abandons the family) and an American father who served in World War II (but refuses to discuss the past), the novel’s protagonist, Katherine, finds comfort and beauty in the way mathematics brings meaning and order to chaos. As an adult she embarks on a quest to solve the Riemann hypothesis, the greatest unsolved mathematical problem of her time, and turns to a theorem that may hold the answer to an even greater question: Who is she? Catherine Chung is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship and a Director’s Visitorship at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Her first novel, Forgotten Country, was a Booklist, Bookpage, and San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of 2012. She has published work in the New York Times, the Rumpus, and Granta, and is a fiction editor at Guernica. She lives in New York City.

Catherine Chung, author of The Tenth Muse. (Credit: David Noles)

1. How long did it take you to write The Tenth Muse?

From when I first had the idea to when I turned in the first draft, it took about five years, with many starts and stops in between.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

My mind! My mind is the biggest challenge in everything I do. I write to try to set myself free, and then find myself snagged on my own limitations. It’s maddening and absurd and so, so humbling. With this book, it was a tie between trying to learn the math I was writing about—which I should have seen coming—and having to confront certain habits of mind I didn’t even know I had. I found myself constantly reining my narrator in, even though I meant for her to be fierce and brilliant and strong. She’s a braver person than me, and I had to really fight my impulse to hold her back, to let her barrel ahead with her own convictions and decisions, despite my own hesitations and fears.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write where I can, when I can. I’ve written in bathtubs of hotel rooms so as not to wake my companions, I’ve written on napkins in restaurants, I’ve written on my phone on the train, sitting under a tree or on a rock, and on my own arm in a pinch. I’ve walked down streets repeating lines to myself when I’ve been caught without a pen or my phone. I’ve also written on my laptop or in a notebook at cafes and in libraries or in bed or at my dining table. As to how often I write, it depends on childcare, what I’m working on, on deadlines, on life!

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

I wish it didn’t turn me into a crazy person, but it does. A pleasant surprise is just how kind so many people have been—withdrawing from the real world to write can be very isolating; it was lovely to emerge and be reminded of the community I write to be a part of.

5. What are you reading right now?

Right now I’m reading Honeyfish—an absolutely gorgeous collection of poetry by Lauren Alleyne, and the wonderful The Weil Conjectures—forthcoming!—about the siblings Simone and Andre Weil, by Karen Olsson. I’m in love with Christine H. Lee’s column Backyard Politics, which is about urban farming, family, trauma, love, resilience, growth—basically everything I care about. It’s been a very good few year of reading for me! I’m obsessed with Ali Smith and devoured her latest, Spring. I thought Women Talking by Miriam Toews and Trust Exercise by Susan Choi were both extraordinary. Helen Oyeyemi is one of my absolute favorites, and Gingerbread was pure brilliance and spicy delight. Jean Kwok’s recent release, Searching for Sylvie Lee, is a stunner; Mary Beth Keane’s Ask Again, Yes broke me with its tenderness and humanity; and Tea Obreht’s forthcoming Inland is magnificent. It took my breath away.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ali Smith and Tove Jansson are both widely recognized, especially in their home countries—but I feel like they should be more widely read here than they are. I didn’t discover Smith until last year, and when I did it was like a hundred doors opening in my mind at once: She’s so playful and wise, she seems to know everything and can bring together ideas that seem completely unrelated until she connects them in surprising and beautiful ways, and her work is filled with such warmth and good humor. And Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is so delicious, so sharp and clean and clear with the purity and wildness of nature and childhood. Ko Un is a Korean poet who’s well known in Korea, but not here—he’s incredible, his poems changed my idea of what poetry is and what it can do. I routinely e-mail his poems to people, just so they know. Bae Suah and Eun Heekyung are Korean fiction writers I admire—I really like reading work in translation because the conventions of storytelling are different everywhere, and I love being reminded of that, and being shown the ways my ideas of story can be exploded. Also, how Rita Zoey Chin’s memoir Let the Tornado Come isn’t a movie or TV show yet, I don’t know. Same with Dan Sheehan’s novel Restless Souls and Vaddey Ratner’s devastating In The Shadow of the Banyan. And Samantha Harvey is a beautiful, thoughtful, revelatory writer who I’m surprised isn’t more widely read in the States.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started writing The Tenth Muse, what would say?

I’d say, “Hey, I know you’re worried about things like finishing and selling this book, and also health insurance and finding a job and not ending up on the street, and all that will more or less work out, but more pressingly, here I am from the future, freaking out because apparently I’ve figured out time travel and also either bypassed or am creating various temporal paradoxes by visiting you now. Clearly we have bigger issues than this book you’re working on or the current moment you’re in, so can you take a moment to help me figure some things out? Like how should I now divide my time between the present and the past? Am I obligated to try to change the outcome of various historical events? Should I visit the distant, distant past before there were people? Should I visit the immediate future? Do I even want to know what happens next and if I do will I become obsessed with trying to edit my life and history in the way that I edit my stories? Help!”

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I don’t see it as a one-size-fits-all situation—I think sure, why not, if it’s fully funded and you feel like you’re getting something out of it. Otherwise, no. The key is to protect your own writing and trust your gut as far as what you want and need.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

My mind, always my mind! Related: self-doubt, self-censorship, and shame.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Back in my twenties, when I was writing my first book, I was eating breakfast at the MacDowell Colony, and this older writer asked me where he could find my published work. I said nowhere. I had an essay coming out in a journal soon, but that was it. He was astonished that I’d been let in and made a big production out of my never having published before, offering to read my forthcoming essay and give me a grade on it. It was weird, but it also sort of bounced off me. Anyway, there was a British poet sitting next to me at that breakfast named Susan Wicks, and some days later, as I was going to fetch some wood (it was winter, we all had our own fireplaces and wood delivered to our porches—have I mentioned MacDowell is paradise?) I opened the side door to my porch, and a little letter fluttered to the ground. It was dated the day of the breakfast, and it was from Susan Wicks. It said: Dear Cathy, I was so angry at the conversation that happened at breakfast! If you are here, it is because you deserve to be here. And you should know there is nothing more precious than this moment of anonymity when no one is watching you. You will never have this freedom again. Enjoy it. Have fun! And have a nice day! And then she drew a smiley face and signed her name. Susan Wicks. I think of her and that advice and her kindness all the time.