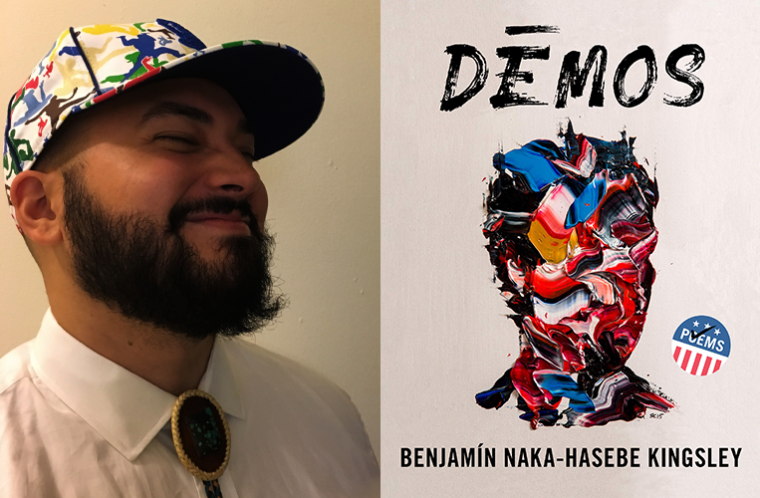

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Benjamín Naka-Hasebe Kingsley, whose third poetry collection, Dēmos, is out today from Milkweed Editions. In Dēmos, Kingsley reveals and speaks out against the violence that pervades American history and society. In an early poem, he addresses and challenges colonizers directly: “colonize / the crevice between my brown lungs, cremate me / in ashy anonymity before / I surface, I breathe, I war.” Writing about historical events—such as the infamous Phips Proclamation, which promised a bounty for the capture or scalps of Penobscot men, women, and children—Kingsley also attends to his own memories and experiences as a person belonging to Onondaga, Japanese, Cuban, and Appalachian communities. “Dēmos is a powerhouse collection of poems by a powerhouse poet,” writes Victoria Chang. Benjamín Naka-Hasebe Kingsley belongs to the Onondaga Nation of Indigenous Americans in New York. The recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, he is the author of Colonize Me (Saturnalia Books, 2019) and Not Your Mama’s Melting Pot (Backwaters Press, 2018). His work has also appeared in the Georgia Review, Kenyon Review, Poetry, Oxford American, and Tin House, among other publications.

Benjamín Naka-Hasebe Kingsley, author of Dēmos.

1. How long did it take you to write Dēmos?

It’s terrible that I know the exact answer. I started writing Dēmos in the fall of 2016. The writing took me almost exactly as long as forty-five’s presidency.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

In ninth-grade biology we had to go through all that genotype/zygote stuff—I say “stuff” because I got through high school by the absolute skin of my shovel-shaped, Native incisors and am still making up for that mislaid literacy. The teacher gave prompts like “Fill out these squares with your family history: eye color, recessive, dominant, knuckle hair, yea, nay, etcetera,” and we kids start filling them out for ethnicity, which is hilariously apropos in its nearly two-decades-ago ignorance—for we so wise in the here and now—as if these cultural markers were some recessive trait you’d maybe or maybe not be born with. I remember writing all four of my “races” outside those Punnet boxes—Onondaga, Cuban, Japanese, Appalachian—and fitting them together as if I’d be able to figure out why I was me, and my homie looks over at me and says, “You’re one messed-up Punnet Square.”

That really stuck with me. A messed-up Punnet Square. I saw myself like that for a long time. That was my earliest memory associated with the book, and now fast forward a decade and a half, and maybe I see myself like that right now. If my monitor goes black and becomes that smudged electric mirror, I’m one messed-up Punnet Square. That’s me. Because I have this intimate, or at least long-standing, relationship with a sterile, probabilistic—easily misread as problematic—diagram. I am a kind of cross-breeding experiment in and of myself. My goal in the specific memory of these poems was to remove the individual “me” and focus on the higher resolution “we,” à la “we the people,” and what a crisscrossed American experiment might yield. I wanted to experiment, to turn that relationship on its ear.

You put that all-too-famous—or way, way not famous enough—Phips Bounty Proclamation on one side of the Punnet. You put my people, our people, on the other. What do you get? The results aren’t as anodyne as eye color. They aren’t as neat as knuckle hair. Not as tidy as, Can she roll her tongue, her “R’s?” When They are dominant, what do We inherit? Is revolution a recessive necessity?

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

When I first presented my work to potential editors, early gatekeepers, they were always like, I don’t hear a unified voice. That happened all the time. To be fair, the corpus of my work is weird. Like, when you aggregate it, I mean, when you collect it all together and present it to a publisher, it’s weird. You get one poem or hybrid narrative essay about Japanese American internment. Then the very next is like in Spanish or broken English or Appalachian Amerikan—shout-out Pennsyltucky, we out here dropping linking verbs! Then the very next poem is talking about how in the Onondaga Nation, within my people, there is a famous legend of the Tadodaho: keeper of the people’s history, of the council fire. The tribe’s Tadodaho is charged with preserving the culture, tradition, and keeping the people’s spirit alive—a very pre-Derridean survivance. In the very next poem, I’m the binary-bucking cub of two mixed-race parents.

I pull as much blood from that “I am multitude” cliché as I can, as I want. What are you? is what editors/publishers were saying in rejection after rejection. There isn’t a unified voice, I heard repeatedly from big-name editors. What are you? is what people have been asking me my whole life. I’ve been teaching college students for a hot minute now, and especially at the beginning—like ten years ago—students would always ask, “Where are you from,” which is to say what are you, what race are you. I used to get asked that outright a lot. We know the whole rigamarole by now—especially if you look remotely ethnically ambiguous. I get out ahead of that somewhat these days, but it initially led to some of the wildest classroom conversations.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I wake up—I try and chug a lot of water—and most days I try and write. My focus is, I hope, first and foremost on effort and not output. I have a lot more control over the discipline than I do the result. I tend to like the adage You don’t have to write, but you can’t do anything else. I write on one of those flash-furniture Costco folding tables. I have a mechanical keyboard. It’s dope.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Kentaro Miura’s Berserk series, Garry Ezzo and Robert Bucknam’s On Becoming Baby Wise: Giving Your Infant the Gift of Nighttime Sleep, Alan Moore’s Absolute Swamp Thing, and Pushcart Prize XLV: Best of the Small Presses 2021. They’re all drastically different enough that the plot lines haven’t been getting confused.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Being assaulted by the police. This is a tongue-in-cheek answer, but maybe a hopefully positive spin on turning absolutely negative real-life circumstances into positive generation or a call to action. A year into writing the book, in August of 2017, I was full-on maced—that big, pumpkin-orange, police-grade conical tornado of crowd-controlling pain—in the face by a cop. I was walking on the sidewalk, more or less minding my own business, where there were a dozen cops arresting and getting real aggressive and violent with this not-even-five-foot young woman of color.

The initial action took place on a narrow sidewalk, and there was no room for anyone to get past. So, they mace me very unexpectedly and I stumbled into oncoming traffic. It’s a busy Saturday night on the most popping street in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania—which isn’t saying a ton, but it isn’t saying nothing. Fight or flight kicked in hard. And yeah I’m not a fighter, lmao. Could you guess I fall into the sensitive poet stereotype? I almost get hit by these cars but I can’t see a damn thing. Your eyes capital S slam shut, trust me. I’m huddled in the corner of this pizza shop, totally alone, and by this point people are screaming—I find out later that the wind had picked up the clouded bloat of pepper spray blast and carried it up to a second-story, outdoor night club wherein the patrons began screaming and vomiting. Long story short, every storefront locked their doors, and I ended up being saved by the kindness of strangers and the cups of murky water they splashed in my eyes. Whew. I have bad eyes already, so I was worried permanent damage was on the table. Military folks and police get to wash their eyes out immediately after their pepper spray/tear gas tests with milk/water, whatever. I had nothing, you know? I did have to get a stronger prescription after that. It sucks to think about. There was a news article written up about it a couple days later. Like I do most things, I decided to turn it into art. I just cribbed straight from the racist comment section and the poem literally wrote itself. I like to think that, in this, and in the precursor poem that more detailed the assault in a more conventional narrative, I’m reclaiming a little of the white-whale space taken up by 2011’s fad(ish) Franco/LaBeouf-ian “uncreative writing.”

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I cannot wait until we can all be together again. I miss the intimacy of hearing undiluted voices. Hugs. Raw laughter.

8. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Senior year of my undergrad I was desperate for a mentor, comradery, and guidance. I synced up with this about-to retire professor who had gone to Iowa in the seventies. After a semester of trying to impress him and taking two of his classes, he told me, “An MFA program might take pity on you, but I hope they don’t.” Bleh. Maybe his heart was in the right place and he just thought I wasn’t ready. Maybe I’ll look back in two decades and be like, Yeah that guy was right. Right now I think, What an asshole. I kept writing. My first semester of grad school in English/Comp Lit I found space in my schedule for a creative writing class, I submitted a creative nonfiction piece about Down syndrome, disabled bodies, and violence. My professor wrote “No.” “No.” “No.” “Offensive.” “Wrong.” all over the essay. They asked me to drop the course. I later found out they actually knew nothing about Down syndrome, and their only experiences had been with TV, with the ultra “high functioning.” My family was on the wrong end of their spectrum, unbelievable, a reality to be erased. They tore me to shreds in workshop. But I believed in the veracity of that essay, and it ended up getting me into an MFA. Unfortunately, anecdotes like that abound. All this to say: I am the most trusted reader of my work. I’ve had enough bad workshops to know that if I don’t have faith in the work, no one will.

9. How did you know when the book was finished?

The only honest answer is that I know a book/essay/story/poem is finished when people in charge, i.e. publishers, will get mad if I change something, lol. Up until then everything is fair game.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Write. I know it sounds banal, but I think everything boils its way down to just write.