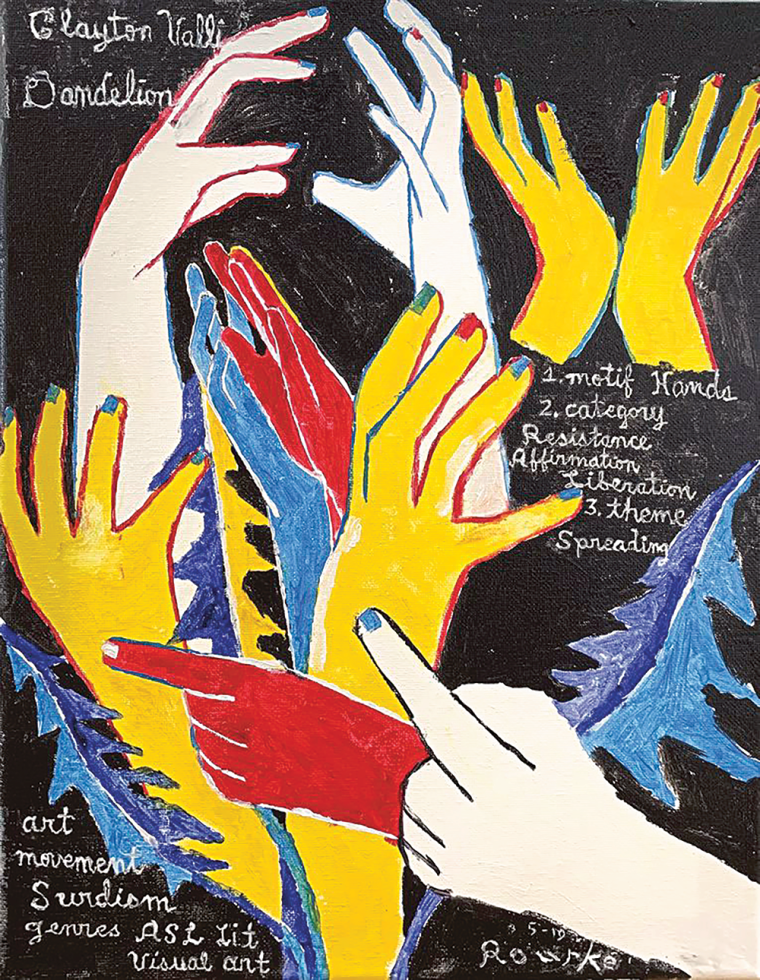

One of the most important and invigorating works of art I’ve ever seen hangs on a wall in my home. Eleven by fourteen inches of oil on stretched canvas, the painting—Identification of a Dandelion—was made by Deaf De’VIA (Deaf View/Image Art) painter Nancy Rourke and engages Deaf gay poet Clayton Valli’s beloved American Sign Language (ASL) poem “Dandelions” as its source text.

Identification of a Dandelion (Credit: Nancy Rourke © 2019)

“Dandelions” is not a poem I expect many hearing poets or nonsigners to have encountered or recognize by name. But I suspect for Deaf folks, and Deaf signing poets in particular, the opening moves of yellow flowers across the lawn—then the swaying “open-5” handshape of the dandelion’s head—incite a similar familiarity and emotional fluency to “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day.” Valli’s “Dandelions” could easily be our “‘Hope’ is a thing with feathers” if Dickinson’s rhyme carried the subterranean political power of “What happens to a dream deferred?” Indeed, “Dandelions” is a poem of resistance and endurance, of Deaf liberation and linguistic sovereignty amid audism and eugenics. It is a critical work in the Deaf poetic canon and an artistic keystone in the movement for authentic sociocultural and historical archive as well as linguistic celebration.

Rourke’s painting is not so much reverse ekphrasis—a work of art made after a piece of literature—as it is artistic analysis, an open investigation, a cross-genre translation. As she describes on her website, the painting borrows the structure of a scientific illustration or botanical print, describing leaf, bud, seed head. But the painting pushes its form metaphorically when the scientific identification begins to include recognition of Valli’s contribution to ASL literature and De’VIA, an arts movement formally established in 1989 during a workshop at Gallaudet University to flip the script on the hearing gaze and instead center the Deaf experience from a cultural, linguistic, and political perspective. Seeing this painting was not the first time I’d understood that ASL poetry might be considered visual art, but it was the first time I realized a borrowed container—employing a different lens or a different genre label, instead of asking again and again for print publishing to become more inventive and inclusive—might help American poetics embrace that which has always been integral to, if not erased from, its diverse lineage.

![]()

As a young poet submitting early manuscripts to chapbook and first book prizes in the 2010s, I found that one of the major roadblocks was the oft-included restriction regarding images or photos. Most guidelines at the dawn of the online submission platform Submittable stated clearly that they did not accept “experimental” manuscripts that included photos, images, drawings, or other ephemera. It seemed implied that the work would be either too unserious or too avant-garde. My early work, much of which included images from ASL dictionaries depicting ASL signs, would not qualify. Visual art was not, in contemporary publishing spheres, poetry. If I wanted to make visual poetry (I’d hardly been educated in visual poetics beyond the more conceptual realm of imagism and concrete poetry, so how could I know), I’d have to look to other avenues. Pictures, it seemed, were for walls; words were for books. And ASL? I encountered it everywhere else: on the street, in the café, on my VHS player, in class, in my home.

![]()

In An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke University Press, 2003), theorist Ann Cvetkovich develops a queer approach to trauma that seeks to broaden our understanding of what an archive can and should include. Cvetkovich troubles not only the category of archive, but also the category of trauma, arguing that everything from sexual assault to AIDS to the history of race in the United States is “inescapably marked by trauma” and therefore may require a more flexible regard for historical reckoning and “documentation” or proof. Traumatized communities are often marked primarily by absence and erasure, by ephemera, by secondhand reports or private, first-person narratives created out of the pressure of public silencing; they are not often included in permanent records, and they do not often fit, with legibility, the categories more official channels—often those complicit in perpetuating trauma—legitimize.

I encountered Cvetkovich’s book for the first time in 2009 as an MFA candidate under the tutelage of Rebekah Edwards, who shaped my thinking about poetics beyond mere political insistence, evidence, and visibility. At a time when queer disclosure and fearless self-identification felt both powerful and risky, Edwards helped me understand Cvetkovich’s proposal to reject existing paradigms of understanding altogether. If “trauma challenges common understandings of what constitutes an archive,” as Cvetkovich writes, perhaps navigating the refusal—and trauma—of eugenics within contemporary publishing had more to do with leaving those publishers behind and creating a new archive altogether.

![]()

When I began drafting my application to be the poet-in-residence at New York City’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, I spent my early mornings and late evenings reeducating myself on De’VIA. I have written before about encountering the artist Joseph Grigely’s exhibitions or watching, gobsmacked, as ASL poets Peter Cook and Kenny Lerner performed in the Flying Words Project, but I had never seen an exhibition of De’VIA artists. I was well out of my MFA when I discovered the work of Nancy Rourke and years beyond the most useful and prescient literature course I took across my three degrees (the one on metaphor in ASL poetry, taught by Peggy Lott, my undergraduate professor). ASL literature is one critical inspiration for De’VIA artists, and studying the ekphrastic-adjacent reciprocity between their work with an eye toward the art instead of the poem—not simply the color-based metaphors or the motifs critical to Deaf culture, but the way movement was conveyed on a static canvas not dissimilar to the limitations of the printed page—made things click.

Deaf and De’VIA artists had been bringing metaphor and poetics into the space of the gallery and the museum for longer than I’d been alive; one need only look at the cover images of most books on Deaf culture or ASL linguistics to find evidence of a rich community of Deaf artists responding to literature. Couldn’t the poems themselves also appear as visual art? Few would look at Rourke’s Identification of a Dandelion and think: This is a poem. But when we encounter the work of Nancy Rourke—or De’VIA artists Chuck Baird, Nancy Creighton, Judy Lai-Yok Ho, Paul Johnson, or Betty G. Miller—suddenly the film of Clayton Valli’s expressive wrists bending dandelioned Deaf resistance across a freshly mowed lawn feels abundantly legible, available, and self-assured as visual art.

![]()

I have long struggled with how to negotiate ASL poetics alongside the compulsory nature of the printed English page under the banner of American poetics. Indeed, the struggle seems to have become itself a career: It has been the primary conflict—material, theoretical, ethical, and political—that has motivated and later cultivated much of my scholarly and creative making, my pedagogical efforts, and my personal community. For those just joining this conversation, the tension is much more complicated than the general public’s ignorance: the fact that ASL is not a sign-for-word replacement for English; that ASL poems are not written in a “foreign” language and so translation is not only thorny political territory, but also often a deeply reductive artistic insult; the cost—prohibitive, human, logistical, and biased—of access via interpreters as a threatened civil right; and the fact that archives of ASL literature exist physically and digitally but not, finally, in print as we expect all literatures to appear.

It’s more than that, still. Audism and systemic language deprivation (yours [hearing] and ours [Deaf]), not to mention regular homegrown ableism, have kept Deaf poets and hearing poets from one another for far too long. The few exceptions—especially that of Allen Ginsberg’s 1984 “hydrogen jukebox” trip to the Rochester Institute of Technology/National Technical Institute for the Deaf (RIT/NTID) Deaf-Beat Summit in Rochester, New York—are more lore than they are model for collaboration. It’s not that ASL poetry summits have failed to happen in the forty years since I was born; it’s that those summits have not crossed paths regularly with those that one might consider among the seasonal happenings of [hearing] American poetics: the Association of Writers & Writing Programs Conference, Dodge Poetry Festival, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the like. It’s true we see the occasional inclusion of Deaf poets on rosters or schedules across the country, but without complete, compulsory, and anticipatory access for those who do not have ASL, language—the very substance of our art—becomes the barrier instead of the bridge. This status quo encourages only Deaf poets writing in English, and even then it encourages in them, in us, a quietly violent assimilation. There are, finally, the poems I am most uniquely suited to making, which are, I hope, the poems each one of us is after—those that only a poet who moves between Deaf and hearing worlds, between languages, between genders, could manage with both signs and words—and then there are the poems I am encouraged to make by the limitations of publication, prizes, and employment: English adaptations.

For an “invisible” disability, Deafness—its language, its literature, its art—boasts a rather robust visual and linguistic culture that is seen, shared, studied, fetishized, and beloved around the world. The trauma of assimilation, language deprivation, and eugenics seems to me the only invisible thing about it. The archive—queer and defiant of category—remains rich, colorful, diverse, and, yes, ephemeral. Perhaps temporality and the temporary nature of its embodied fullness is the creative restraint—the feature, not the bug.

![]()

Ekphrasis in Air, my exhibition as part of Sixth Stanza, was installed on the sixth ramp of the Guggenheim Museum from November 8, 2024, to March 9, 2025, and featured three bays of stretched canvas screens projecting looped video recordings of seven Deaf poets signing ekphrastic responses to the architecture and art of the Guggenheim. The poets—Raymond Antrobus, Noah Buchholz, Abby Haroun, Raymond Luczak, Douglas Ridloff, Rosa Lee Timm, and I—range in international renown, relationship to Deafness, artistic commitment to signing, style, lineage, and politics. Some of us have books with English publishers. Some of us publish in ASL gloss, a written representation of signs using English words, or have traversed the outmoded restrictions of visuals in printed texts. And some of us have never published anything at all in a traditional market. Some of us have international audiences for our performances, rack millions of views on our ASL videos, and have received worldwide acclaim as experts of Visual Vernacular (VV), and some of us performed our work in sign language for the first time at the Guggenheim’s epic evening of Deaf and hard-of-hearing poetry, Sound/Off, in December 2024.

The poems resided at the top of the museum’s spiral, which marked the finale of many visitors’ upward ascent through abstract paintings rich in color, shape, and geometric surprise. When they encountered the signing poets on-screen—much larger than life and rich in graceful, fluid movement against the curved white walls of the museum’s final revolution—they were primed well for the uncategorizable beauty of bodies and language as art. Fluency—or its failure—seemed to fall away. There was an opening for engagement akin to what teachers have recommended for years when reading Shakespeare: Just let it wash over you. Cvetkovich reminds us in Archive of Feelings that a queer archive “creates publics by bringing together live bodies in space,” and the experience is “not just about what’s onstage but also about who’s in the audience, creating community.” After so many months of curation meetings and installation walk-throughs—after so many years of pushing and blending different modes and genres to permit what was now just plainly in front of me—I was rather stunned to see the exhibition open; I had forgotten, somehow, the bays would also be full of people, of a public, of the “readership” page poetics makes largely invisible. I watched the visitors read. I read alongside them. I responded in tandem with their bodies, and together we made new poems—contrapuntals, perhaps—in a kind of energetic reciprocity we page poets rarely feel, even at good readings. I got that deep buzz that ASL cafés of the early aughts used to carry, the sense of community among strangers, of shared language even. I don’t know if it was a dandelion, exactly, but there were seeds being planted, all around.

Deaf, genderqueer poet Meg Day is the author of Last Psalm at Sea Level (Barrow Street, 2014), winner of the Publishing Triangle’s Audre Lorde Award and a finalist for the 2016 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and the coeditor of Laura Hershey: On the Life & Work of an American Master (Pleiades Press, 2019). Day is the recipient of an NEA Fellowship in Poetry whose work has appeared or is forthcoming in Best American Poetry 2020, the New York Times, Poetry, and elsewhere. Day, the 2024 Guggenheim Poet-in-Residence, is an associate professor of English and creative writing in the MFA program at North Carolina State University.