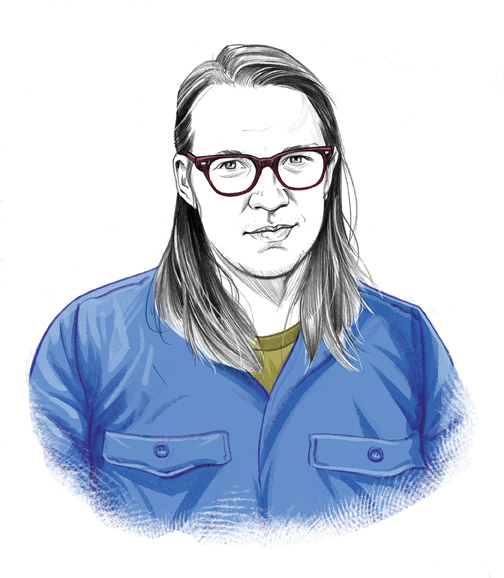

Justin Boening

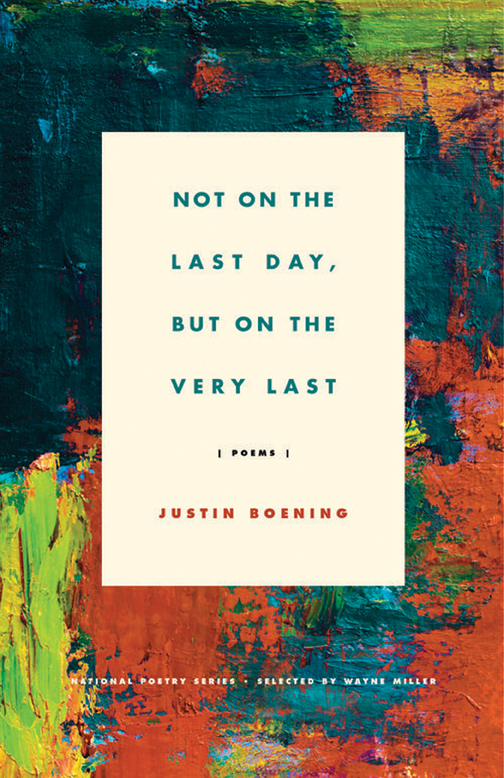

Not on the Last Day, but on the Very Last

Milkweed Editions (National Poetry Series)

“does sadness leave us?

Is that the source of sadness?”

—from “Banquet”

How it began: The book’s title is taken from the thorny end of a Kafka parable called “The Coming of the Messiah.” It finishes: “The messiah will come on the day after he is no longer required, he will come on the day after his arrival, he will come not on the last day, but on the very last.” I’ve seen others attempt to negotiate these paradoxes by changing the definition of last day or very last. I guess that makes as much sense as anything else. But for me, this is a portrait of a savior who comes, not belatedly, but by not coming at all. I think it may have been this parable that put me on the road toward writing a book of failures, of mistakes, which is how I’ve come to understand the collection—a book where one learns to become a god by being unrecognizable, for example, or where one rules the world by being the only one in it. I don’t know. I’m probably the last one who should be talking about such things. More generally, though, I think what compelled me to write this book may have been distance from God. For me, poetry is an expression of this desire to reach out, not to communicate per se, but to get closer to whatever it is that’s always just beyond reach or sight. Maybe that sounds too lofty, but it’s a longing I’ve felt all my life, and a longing I’ve often associated with the essence of whatever it is I’ve called “human.” Stevens finishes his poem “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour” by saying, “We make a dwelling in the evening air / In which being there together is enough.” I think that about sums it up for me—what compelled me to write these poems.

Inspiration: The unshakable belief that poetry is absolutely necessary, that it’s inextricably linked to language itself, and that, therefore, it’s one of the most human things we’re allowed to participate in.

Influences: As far as writers go, I return most often to Franz Kafka, Wallace Stevens, Clarice Lispector, John Berryman, Sylvia Plath, Mark Strand, and Lucie Brock-Broido.

Writer’s Block Remedy: I almost never push it. If a poem is frustrating me I walk away, watch some YouTube, read writers who know what they’re doing. Distraction is good for poetry, I think, maybe because it breeds uncertainty. In fact, I feel I do my best writing when I’m not writing at all.

Advice: Hold off as long as you can. And once you lose your patience, only send the work to people and presses you already respect and trust.

What’s next: Lately I’ve been putting a lot of my energy into a new magazine and press called Horsethief Books that Devon Walker-Figueroa and I have started together. As far as my own poems go, with the loss of so many friends and luminaries I’ve been writing elegies as of late.

Age: I’m 35 and will be turning 36 on February 13 (yes, I was born on a Friday).

Hometown: I was born in Saratoga Hospital, on a holiday down to see the ponies. I call Glens Falls, New York, my hometown though, since I ate my first corn on the cob there, stole my first bike there, etc. I moved to New York City when I was six—pretty young—so that’s a home for me as well, though not my origins. Recently, I was eating a 1:00 AM chicken fried steak in Missoula, Montana, at a dive called the Ox. Two guys, who had just finished playing poker at the front card table, stood up suddenly from their counter stools. One guy walloped the other guy in the eye, snatched up his rucksack, and hustled out the front door. No one called the cops. Few were alarmed. That’s the place I’ve lived the longest, actually—Missoula is another home.

Residence: Iowa City.

Job: A living? Maybe you could call it that. I teach and edit, mostly.

Time spent writing the book: Well, there are some whispers from poems I wrote while I was a graduate student, but they’re really only whispers. The oldest poem in the book is one I wrote the moment after I handed in my graduate thesis—that was in 2011. The newest poem is one I wrote in 2015. So I guess that means four years?

Time spent finding a home for it: I sent out bashfully in 2013, and then in earnest until the book was taken in 2015.

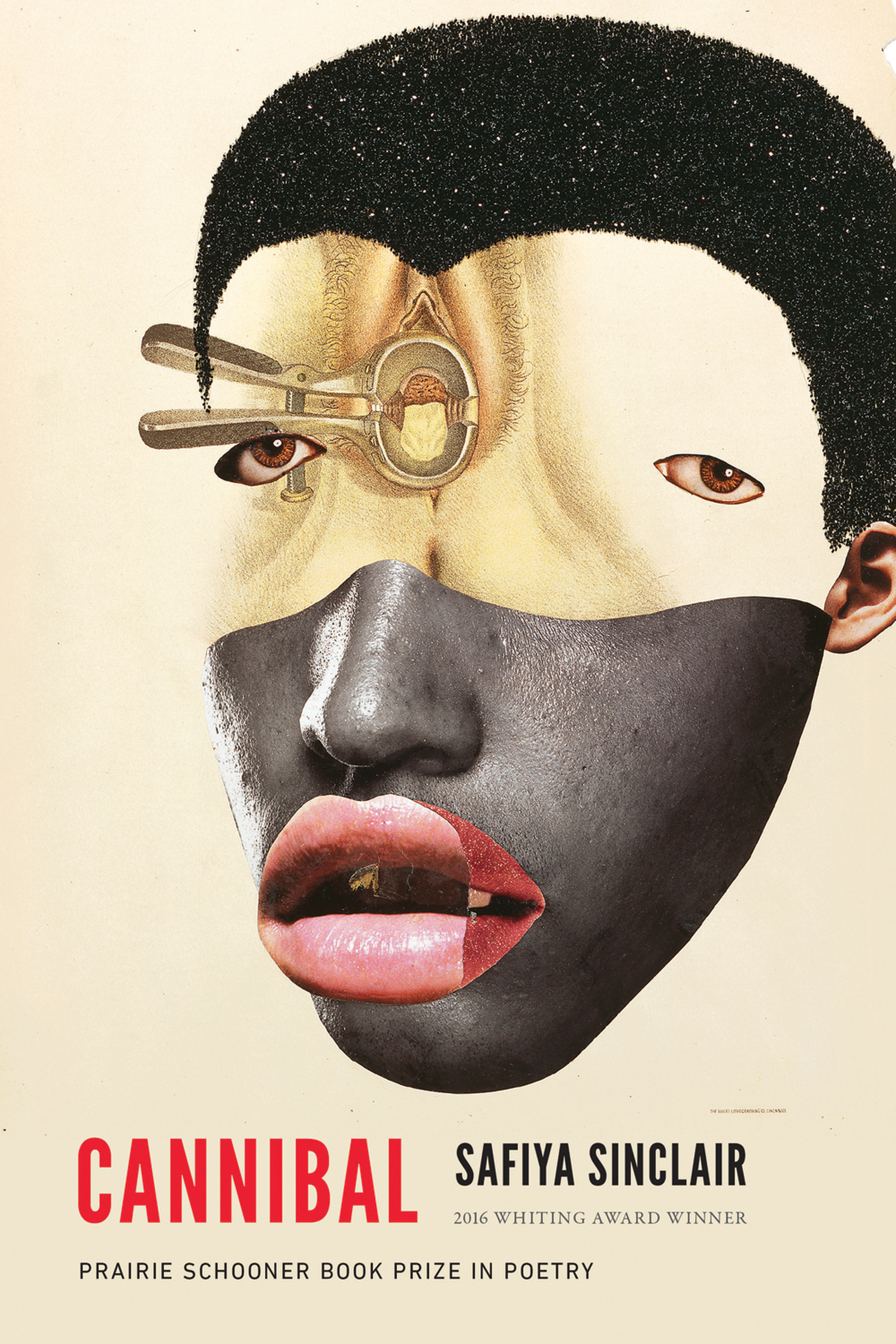

Safiya Sinclair

Cannibal

University of Nebraska Press (Prairie Schooner Book Prize)

“Tell the hounds who undress

me with their eyes—I have nothing

to hide. I will spread myself

wide.”

—from “Center of the World”

How it began: I began writing poetry as an act of survival. Faced with the silencing exile of womanhood in an oppressive household and a patriarchal society that discouraged me from speaking and thinking, the only way to make sense of my burgeoning selfhood was here on the page, by writing it down. Then, plagued still with the strange linguistic exile of writing in English, the language of the colonist, while dancing wildly in the brazen self of Jamaican patois, the only way to unfracture this amputated history was by making a home for myself on the page, and building new modes of language by writing poetry.

When I was younger I was very dismayed by how little of myself and my family I could trace into the past, and was very inspired by the oral folklore and storytelling tradition passed down by my mother and my aunts. It became very clear to me that this oral folklore and storytelling was a matriarchal tradition—a way of preserving our history, both family history and Jamaican history. This not only incited and inspired me to write Cannibal, but it was also a way of saving my own life, of making a record of our songs and mother tongue, and paying tribute to the women who have woven our words and days into existence.

Finally, it was imperative for me to confront the macabre history of the Caribbean itself—to expose the postcolonial roots of violence here; to explore how being “Caribbean” was so closely linked to being “savage,” being cannibal. By confronting the ugly language and prejudices that continue to plague all people of the African diaspora, I hoped to renarrativize the toxic gaze of white supremacy at home and abroad, to shatter its fictions through the shared ritual of poetry.

Inspiration: Always in my ear is the ghost meter of the Caribbean Sea, its old rhythm and singing. The possessed tempo of Pocomania, and the fire-root of duende. I am continually inspired by the fertile landscape of Jamaica, which fevers my dreams—our lush hills and blooms, our heavy fruit trees. The way nothing here grows politely. The wild animal of my childhood and its green river of memory.

I’m fascinated by Goethe’s lifelong search for the “Primal Plant,” from which grew my own notion of the black woman’s body as that elusive Primal Plant, the first site of exile. Early on in college I was very startled by Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, which showed me the wild possibilities of breaking form, how I could build my own labyrinth of mythification as a way to honor and transfigure family, a way to alchemize our folklore. I’ve also been writing from a desire to dismantle Western texts like Shakespeare’s The Tempest, to repossess Caliban as a throat through which the poems could sing, our one-drop rhythm transgressing violence and its lingering exile, a linguistic rebellion forged here through the music of linguistic mastery.

Influences: The poets, artists, and writers who feed the fire and bloodroot of my family tree are Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, Lucille Clifton, Frida Kahlo, James Baldwin, Federico García Lorca, Caliban, Aimé Césaire, Caravaggio, Franz Kafka, Gabriel García Márquez, Paul Celan, Rita Dove, Wangechi Mutu, Derek Walcott, and Kamau Brathwaite.

Writer’s Block Remedy: I can’t say I’ve ever truly reached an impasse in my work. There’s still so much unwritten of Jamaican history, folklore, and culture, still so much of our rich lives that I need to give voice to, in my own small way. Because I read so feverishly, and am always engaging with topics outside of my field—mostly science, history, and philosophy—I’m always finding new ways to enter into a poem, then discovering how many ideas are already in dialogue with each other in that lyric space. I am often so possessed with language, with the roots and wide-ranging shadows of words, that I’m always chasing one word or another down a new corridor of inquiry. If I hit a wall, I’ll listen to music that opens a window unto memory and centers me in a specific time and place, or I’ll reread authors who’ve dazzled and nurtured me, who take the top of my head off. Both English and Jamaican patois are two deep oceans ready-made for diving. And I dive, unabashedly. There, I find the far-reaching tentacles of naming and wording in our society so expansive that I would have enough material to interpret for a lifetime.

Advice: Take your time. Read widely, expand your references and vocabulary; make the poems sing. Nowadays I think there is such a rush to publish a first book, and many poets might feel pressured to send something out that isn’t quite ready. My strongest advice is to be unafraid of waiting, to sit with your words and work until you’ve cultivated them into something flourishing. Live inside the book until you’re certain you’ve grown something lasting, a bloom of your absolute best self. You only have one first; make it count.

What’s next: I’m currently working on a memoir about growing up in a strict Rastafarian household in Jamaica, and feeling estranged in my own country (Jamaica is a heavily Christian country, and Rastafarians are an oft-ostracized minority.) At that same time, I began feeling exiled by my blooming womanhood, and eventually had no choice but to rebel against a religion and a home that made no room for me.

Age: 32.

Hometown: Montego Bay, Jamaica.

Residence: Los Angeles.

Job: I’m a third-year doctoral student at the University of Southern California, where I’m getting my PhD in literature and creative writing.

Time spent writing the book: The bulk of the poems were written in the three years I was in the MFA program at the University of Virginia. The book was my final thesis, and I spent a few months after that rearranging, focusing, and editing the manuscript. One poem snuck into Cannibal that was written in college six or seven years ago. After the book was accepted, I was still tinkering a bit with structuring, and I knew it needed three more poems (circling around a specific theme) to make it cohesive and complete in my mind, so I slipped three new poems into the manuscript, right down to the wire. Those last three poems were completed in September 2015.

Time spent finding a home for it: I waited to send out the manuscript (and most of its poems) until I felt certain that it was ready to breathe on its own full-bloodedly. The fall after I graduated from the University of Virginia I started submitting Cannibal to prizes, and was really fortunate to have the book accepted to a couple of places by the summer of 2015. Cannibal won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry that June. So it was a year or less of sending it out into the world until it was accepted—a fitting nine months.

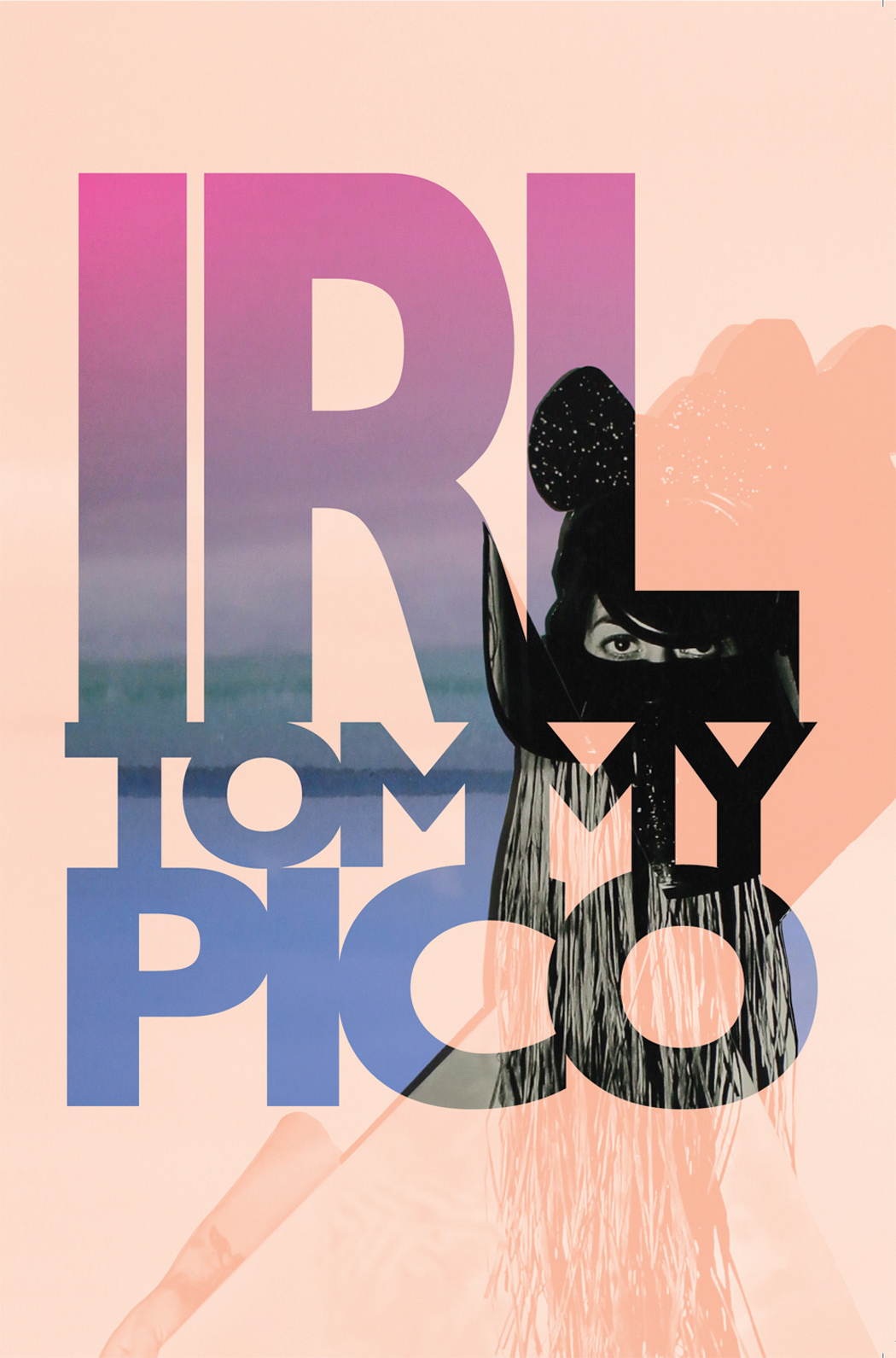

Tommy Pico

IRL

Birds, LLC

“The stars are anxious.

What version of yrself

do you see when you

close yr eyes?”

—from “IRL”

How it began: I was torn between a stable relationship and predictable future with a boring dude, and an exciting but uneven fling with a pretty young thing. It kind of broke open all the similar divisions inside me: how to transition into my thirties; hailing from the foothills of rural California but living in the busiest city in America; being a modern, queer, indigenous person with a lot of inherent self-love in a world that tries to deny me life, dignity, liberty, etc.

Inspiration: Survivors, femininity, experiences that happen within the span of ninety minutes (like movies [sometimes sex]).

Influences: A. R. Ammons, Beyoncé, Mariah Carey, Amy Winehouse, Janet Jackson, Nicki Minaj, June Jordan, Muriel Rukeyser, Jeffrey Yang, Sherman Alexie, James Welch, Joy Harjo, Louise Erdrich, Chun Li, Storm, etc.

Writer’s Block Remedy: I watch a movie—or a film, if that’s your vibe. Seeing something begin, build, and end in a certain amount of time gives me faith in a creative faculty.

Advice: Keep the faith, b, keep the faith.

What’s next: I’m working with Tin House to finish up the final edits on Nature Poem, the follow-up to IRL coming out May 2017. I’m about halfway through writing book number three, Junk, and have started Food—the final book in the four-part series I started with IRL. Also a roundtable-discussion-type podcast called “Food 4 Thot” about four multiracial, queer writers in New York City discussing literature, sexuality, and pop culture (hashtag elevator pitch) whom I met at the 2016 Tin House Summer Writer’s Workshop. Teaching long-poem workshops. Also being a good friend, a good lay, and a good human.

Age: 33.

Hometown: The Viejas Indian reservation of the Kumeyaay nation.

Residence: New York City.

Job: I have approximately sixty-nine side piece jobs, including teaching/touring/freelance stuff, and a main thing that involves writing—but I’m not at liberty to talk about it just yet. If I told you I’d prolly have to kill you.

Time spent writing the book: Officially, I wrote the book from May to August 2014 in an office in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, facing the entire trunk of Manhattan, but in a way I was writing the book for thirty years.

Time spent finding a home for it: I sent it to allllll the book contests and once or twice even got a personalized rejection, but mostly sturdy no’s from everybody. I don’t blame them, it’s a weird nonstandard poem and the initial manuscript was probs 70 percent realized. Sampson Starkweather at Birds, LLC saw me read one night in the city and asked me to send him something. Thankfully they had enough faith in my voice and work ethic to help me guide the book toward its final form.

Dana Isokawa is the associate editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.