In 1972, Paris Review editor George Plimpton and a band of writers walked up Fifth Avenue in Manhattan selling their own books from pushcarts, protesting their publishers’ sluggishness in promoting and distributing their work. Inspired, Bill Henderson, a thirty-one-year-old editor at Doubleday, and his then-wife, Nancy, started Pushcart Press in their studio apartment in Yonkers, New York. Named after Plimpton’s demonstration, Pushcart aimed to elevate overlooked writers and small presses.

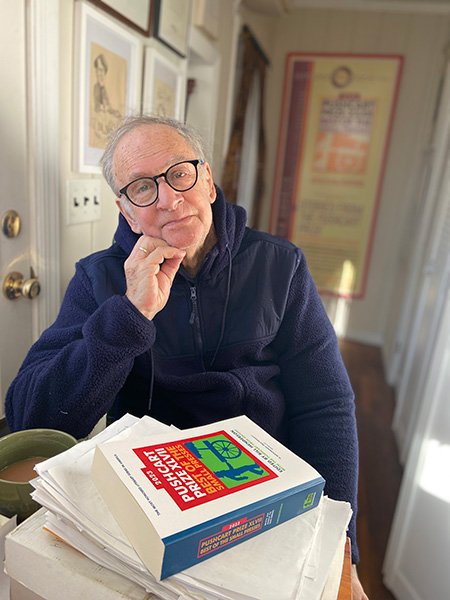

Bill Henderson of Pushcart Press. (Credit: L. Frances Henderson)

“I was, and still am, angry about writers who are suppressed by commercial publishers,” says Henderson, who in 1971, under the pseudonym Luke Walton, published his own novel, The Galápagos Kid, with Nautilus Books, a press he founded with his uncle in New Jersey after his book had been rejected by all the major New York publishers.

It has been fifty years since Pushcart released its first book, The Publish-It-Yourself Handbook (1973), informed by Henderson’s experience with Nautilus, to offer inspiration, encouragement, and instruction for writers on how to print and disseminate their work. Featuring essays by Anaïs Nin, Stewart Brand, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, and others, the best-selling handbook sold over 75,000 copies in four editions and ten printings. Now considered one of the most influential publishers in America, Pushcart has released more than sixty titles—primarily collections of poetry and literary prose awarded the Pushcart Prize.

The annual Pushcart Prize anthology includes poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction published during the previous year by small presses. Editors may nominate up to six selections published by their presses for each volume; there is no entry fee, and submissions are accepted by mail. Some two hundred volunteers also offer nominations. Overseeing operations from a shack in his backyard on New York’s Long Island, Henderson collaborates with guest editors to select the annual prize-winners published in each anthology. This year’s edition features more than sixty pieces chosen from about eight hundred presses.

The idea for the anthology, “to celebrate people who’d dodged the commercial racket and published their own stuff,” arose soon after the handbook’s success, Henderson says. The choice to award writing with a “prize” stemmed from the evaluative process involved in selecting works to include in the anthology: “We ask so many people to judge and help out,” Henderson says. “Also, it is a fun contrast to the Pulitzer Prize.” With founding editors Ralph Ellison, Joyce Carol Oates, Paul Bowles, and others, The Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses was published in 1976—by some accounts helping to spark a small press revolution: “Prior to 1976 there were three, maybe four small presses,” Henderson says. “Soon after the prize there were several hundred more. Now you can find directories of thousands of small presses.”

From the beginning, Pushcart garnered surprising support from the very establishment it criticized. “The New York Times Book Review editor in chief Harvey Shapiro, a small press poet himself, ran features and reviews of the Pushcart anthology for eight years in a row,” Henderson says. “John Baker, the editor in chief of Publishers Weekly, at the center of the commercial storm, really liked and supported our books and prizes.”

With such high-profile endorsements, inclusion in the Pushcart anthology has become a marker of prestige. For some it has even been a bridge between independent and mainstream publishing—perhaps an ironic twist for a press that began in resistance to commercial literature.

Wally Lamb, for example, credits Pushcart with jump-starting his career, which now includes six New York Times best-selling novels. In the early 1990s, Lamb was ready to give up writing. “I was going through a difficult year—my mother had a couple of strokes, my father had Parkinson’s, we had just adopted a four-year-old boy, and I was teaching high school full-time,” he says. But after a story Lamb published in the Missouri Review won the Pushcart Prize, everything changed. “An agent who saw my piece in Pushcart contacted me and asked if I was working on anything longer and if I had representation,” Lamb says. “That validation jet-propelled me to take a leave of absence from teaching and start on my first novel.” That book, She’s Come Undone (Simon & Schuster, 1992), would become a No. 1 New York Times best-seller.

Yet what makes Pushcart special to Lamb is the press’s grassroots sensibility. “In Pushcart, you’re nominated by other writers or publications, which feels more legit than a panel of judges who aren’t writers themselves,” says Lamb, who has nominated writers for the Pushcart Prize and assigned the anthology as a textbook in the writing classes he teaches at a university and for incarcerated women. “It’s not the canon of white men but way more diverse and representative of women and writers of color. It reflects who we are, and that was true right from the beginning.”

Pushcart’s elevation of independent publishers has also played a role in its ability to outlast many other presses. “Pushcart has stayed relevant for the past fifty years because Bill saw and continues to see the essential role literary magazines and small presses play in supporting writers and writing in our country,” says Mary Gannon, executive director of the Community of Literary Magazines & Presses. “It’s been driven by mission and singleness of heart, transcending trends and the ups and downs of publishing.”

Henderson hopes to maintain that legacy: “I want Pushcart to continue celebrating literature for the next fifty years,” he says. “There’s a hell of a lot more out there than electronics and Twitter fights.”

Gila Lyons’s writing on mental health and social justice has appeared in the New York Times; O, the Oprah Magazine; Ploughshares; and other publications.