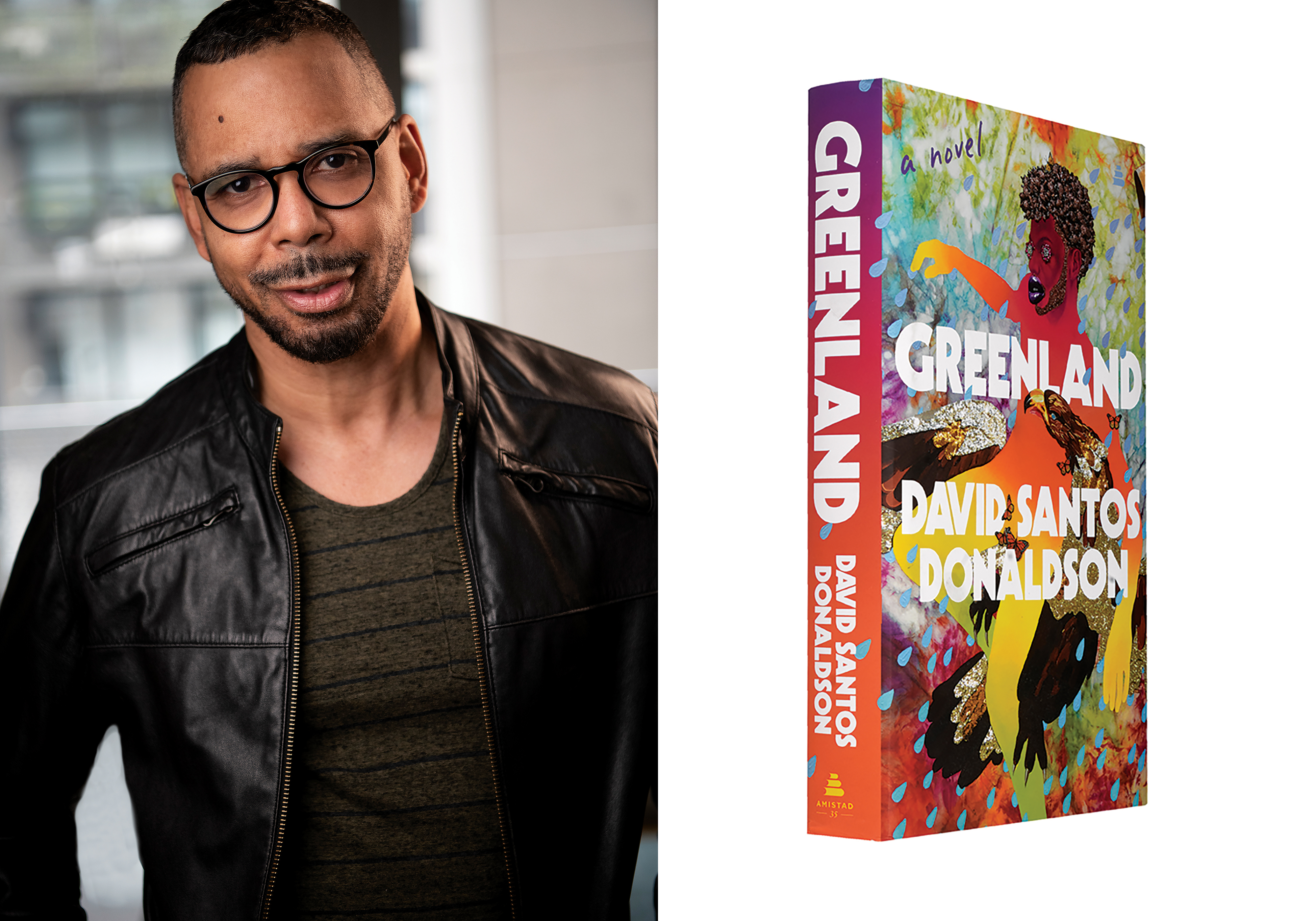

David Santos Donaldson

Age: 60. Residence: Brooklyn, New York. Book: Greenland (Amistad, June 2022), a novel-within-a-novel concerning a young author writing about the secret love affair between E. M. Forster and Mohammed el Adl—in which Mohammed’s story collides with his own, blending fact and fiction. Agent: Tom Miller. Editor: Tara Parsons.

I had given up on the idea of getting published in my lifetime. By the time I reached forty, with an awful sinking in my chest I faced a brutal reality: I would never make one of those famous lists of “Writers Under 40.” I’d been haunted by an article I read in which Kazuo Ishiguro said most great novels were written by authors under forty. At first it sounded ridiculous. What about late bloomers like José Saramago and Penelope Fitzgerald? But there were multiple examples to back up Ishiguro’s claim. Sad and somewhat embittered, I began to mourn the artistic life I’d imagined for myself. When I turned fifty, and my latest novel was not picked up by editors, I faced the harshest reality of all: Not only would I probably never write a great novel, but I would also probably never get published.

There is a great teaching from Atisha, the eleventh-century Bengali Buddhist master: Abandon all hope. Initially this seems like accepting defeat. But the wisdom behind this teaching is that once we give up waiting for our fulfillment to happen in the future, we can fully accept what and who we are right now. Ironically I found that writing from that place of acceptance allowed me to write more honestly and urgently and even to face obstacles I may have been putting in my own way on the road to publication.

For years I got responses from editors who praised my writing but ultimately declined to publish it. The most common response was they couldn’t identify a viable audience for my work. I never understood this because growing up as a queer, Black Caribbean boy, I had easily identified with nineteenth-century Russian and British novels—Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Eliot—and the outer trappings of their worlds were nothing like mine. Couldn’t my writing also matter to those who didn’t share my exact identity and worlds?

I decided that since there wasn’t an audience for my work (according to many editors), I would write whatever I wanted, just for myself. I wouldn’t try to be acceptable to a wider audience. Writing, I realized, is what gave my life meaning—published or not. Writing is also an odd compulsion for me. If I don’t have a writing project, I can barely orient myself. When I’m deep into writing a novel, everything I encounter seems meaningful and somehow relevant to my story. I feel alive, and I’m constantly responding to the world.

Once I accepted that I had to write for myself, the idea of getting published became less essential and more of a game, an interesting puzzle to solve. If it were possible, I asked myself, how could I get my more personal work to somehow fit into the demands of the market? I studied some recent best-selling literary novels and came up with some common stylistic traits. I then experimented with applying those traits to my work: very short chapters and first-person narratives with straightforward prose, for example. But I never compromised my content.

It eventually worked. My next novel, Greenland, was picked up for publication. My process seems to confirm a certain truth: Once we abandon all hope, we are free to be alive in the moment, and when that immediacy makes it onto the page, we give ourselves the best chance of making art others can respond to in kind.

While Ishiguro may have a point about writers under forty, I am no longer haunted by his ghostly words. Great novels have—and will continue to be—written by writers over fifty.